Fond memories of fresh air, freedom and fun were evoked at the Wind Mill reunion.

NO doubt in the belief that what goes around comes around, they held a gloriously nostalgic reunion last Saturday – a celebration of time flown, a grandmothers’ meeting – in the happy hamlet of Wind Mill.

It’s west of the A68, near Toft Hill in County Durham, half-hidden down Memory Lane and with a population of fewer than 50. There’s a Georgian post box, a delightful little Methodist chapel and a farm with a notice on the gate to advise that passers-by are being watched.

Too true. Never having seen so many folk in all their born-bovine days, a herd of cattle stuck its collectively curious head over the hedge, like gawpers at a B-list wedding.

And not just Wind Mill. Morley, barely bigger and but a mile away, turned again, too. They always did do things together. Morley had the school and Wind Mill the chapel.

They talked of happy days and hoppy days, of a childhood when forever it seemed spring, of days of innocence and innocents and of the Sunday School anniversaries, perched precariously on a platform in order to say their piece.

“We thought we were facing the whole world,” said Joyce Davies, “not just half of Wind Mill.”

They remembered, too, the trips to Redcar and South Shields – “we thought South Shields hundreds of miles away” – recalled the post-war New Year’s Day parties, also in the chapel, with games like trencher, winkie, shy widow and, inevitably, postman’s knock.

Trencher involved spinning a bread board, calling someone’s name and expecting them to catch it before it hit the ground. Lips sealed no longer, most of the others appeared to involve kissing.

“Put that in the paper and you’ll have us thrown out,” said Joyce Simpson, with Freda Jewitt the chief organiser.

“Never mind that,” said Billy Lowson Gelley, one of precious few men in attendance, “if there was all that kissing, what happened to mine?”

A U-bend exhibition would be special if held in Wind Mill chapel, but this was better yet.

“Here’s Greta,” they said, “here’s Pearl” and “here’s the Lee girls”, though girls, in truth no longer. If in doubt they simply said “Eeeeh, is that you” and the funny thing seemed that it almost always was.

They’d baked, just like they always did. Asked to bring a little something and could have fed the five thousand.

The sun shone, the daffs defiant. Remembrance day, refulgent.

FREDA had brought aged Auckland Chronicle cuttings of the Wind Mill Merrymakers – averaging £9 a concert, it was reported – and of wartime efforts for the Red Cross.

“My mother was a great cutterout,”

she said, though Freda herself no longer did so. “It was becoming depressing,”

she said, “all deaths.”

The Red Cross cutting spoke of something happening “before the commencement”. The sub-editors must all have been at war.

It could have been almost anywhere, of course, anywhere from a Just William childhood when boys and girls went out to play and none worried that they might come to harm, save for a clip around the ear from a farmer unwilling to forgive their trespasses.

“You were welcomed in every house,” said Joyce Simpson. “I know you have rose-tinted glasses, but really it was perfect.”

“It was lovely, a place where everyone knew everyone else,” said Margaret Kirby. “It wasn’t so much a village as a big family, where you made your own entertainment. These days they don’t know how to.”

They recalled Sunday mornings in Morley, when Quadrini’s horse and trap would trot up with ice cream and, with luck, Butterknowle Silver Band might blow by, too.

They recalled the duck pond – Morley docks – the little school, the Tower House garden parties, the sledging down Wind Mill pit heap, the Featherstone’s bus rides, the fresh air, the freedom, the fun.

They’d found the Sunday School register, too – 12 girls and 14 boys in 1938, almost as many 20 years later.

Now, of course, there are none.

They talked endlessly, talked like the long-lost friends that they were, talked when memory faded of Mr Thingy, fell silent as a Sunday-best sermon only when tea triumphantly appeared and challenged them to move the mountain.

They remembered Granny Hodgson, who ran the little shop until 1936, sold the paraffin for the lamps. “You may telephone from here,” said the enamel sign outside, though few ever did.

They remembered Aunty Mary, the Sunday School superintendent who may genealogically have been Aunty Mary to quite a few but, affectionately, effectively, to them all.

It was 4.30pm, two-and-a-half hours in, and still none hurried homeward.

In truth they were home already, now scattered to all parts but grist to the Mill once again.

ROSAMUND Dowson always knew there was a world beyond Wind Mill, took off in her 20s on a solo trip to the States, was a bit taken aback when a handsome American asked if he might occupy the next seat on a Greyhound bus.

“It’s a free country,” said Rosamund, inarguably.

Before the 250-mile journey was over – you have to be quick on a Greyhound – he’d asked if she’d like to attend an Independence Day celebration in Kansas City, Missouri.

“I’m English, why on earth should I want to do that?” said Rosamund.

“There’s hamburgers, hot dogs and salad,” said Tom Brazelton, a man who clearly knew the way to a girl’s heart.

Before the holiday was over he’d proposed, she’d accepted, and all that remained was to ring home with news guaranteed to cause a stiff breeze around Wind Mill.

Forty-odd years later they still tell the story but as if in chorus, wordfor- word, recall how Rosamund’s father had told her to get herself home at once and how her folks had gone dashing round to her grandmother’s to break the extraordinary tidings.

“He’ll be fine,” said wise old gran. “I’ve never known anyone as parky about men as our Rosamund”

After a few years in America, they returned to England in 1975 – “Harold Wilson’s government changed the law, to allow English women to bring their husbands over,” they say, as one – and now live in Toft Hill, a couple of miles up the road.

Accent still intact – he spells his surname with a “zee” – Tom says he’s got used to the old place, is particularly grateful for the NHS.

“It’s a lot better than we’ve got in America.”

Rosamund – “I was very independent” – remains glad she caught that Greyhound, too. “This country has been kinder to us than America ever was. We’re going nowhere now.”

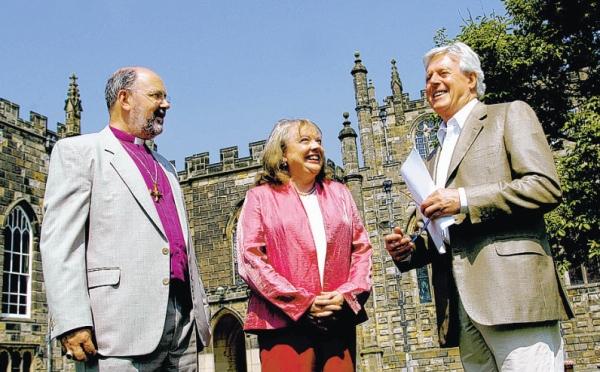

The Bishop and the bongies

Dr Tom Wright’s appointment as Bishop of Durham was announced on February 11, 2003.

Right irreverend, we’d supposed him to bear a passing likeness to the late Clement Freud, noted that he’d delivered more visiting lectures than a peripatetic mother-in-law, suggested that he remember whence he was bound.

He’d spoken at his press conference of the need to “engage post post-modern society”. In West Cornforth, said the column, they talk of little else.

He and his wife Maggie, she of the vertiginous heels, have become friends of us both. On a recent visit to Auckland Castle – they do a splendid supper – he’d mused upon the attractions of academia, to which now he will return.

Bishop Tom was born in Morpeth, supports Newcastle United, reckons Sunderland’s FA Cup final win in 1973 the best match he ever saw, hoped to invigorate the diocesan clergy cricket team.

“I shall certainly encourage them all I can, but unfortunately cricket is a rather long game,” he said, diplomatically, at the time. The team folded, one of his disappointments.

There have been many achievements.

He’d also addressed his complete absence of parochial experience. “I don’t think it completely disqualifies me,” he said. “It does seem to me that sometimes when an area is rather parched, you should send in someone who is an expert on digging wells.”

Perhaps chiefly he will be recalled as an eloquent communicator, effectively able to get across his message whether in university hall or parish pulpit and without reference (unless they know differently in West Cornforth) to post post-modern society.

Durham will much miss him – regret, too, that there will be another year without a diocesan bishop. Just weeks after his consecration he’d received a letter from the Church Commissioners rubbishing a Sunday newspaper report that the castle was to be sold for £10m to help offset great holes in church finances.

Whether Tom and Maggie Wright will be the last Dunelmians to hold court amid its splendours remains anxiously to be seen.

THE new bishop’s first parish service had been at Hamsterley – a spring stroll across the fields from Wind Mill. He’d arrived with a small attache case – “the sort of thing in which other men might keep their cheese and pickle sandwiches”

– but emerged in flamboyant episcopal fig.

Had the name Marvo the Magician been written on the case, we wondered, and were a little disappointed to learn that his chauffeur (“toting a portmanteau of fortnight-in-Blackpool proportions”) had made straight his path a little earlier.

Since Christmas was coming, Dr Wright quoted in his sermon a letter from David, an apparently bright eight-year-old in Oxford.

“If more people pray for the same thing, is God more likely to answer?

If so, will you please pray that I get a go-kart for Christmas?” There was a winsome drawing, too.

By the following March, he’d received another letter and another drawing from David – quite possibly nine by then – reported to a young congregation at Middleton St George.

His new friend, who’d got his gokart, reported that his pal Sanjeet had stolen his bongies – marbles, apparently – didn’t give a “dam” but still wanted to hang around with him. The question, babes and sucklings, went to the heart of Christian teaching.

“Should I forgive someone if they’re not sorry?”

To some it was beginning to sound too clever-by-half, the work perhaps of an ecclesiastical Henry Root.

Bishop Tom thought not. “I have about a ten per cent suspicion that there is an adult standing behind,”

he said, and thus was 90 per cent mistaken.

Enquiries in Oxford revealed the sender to be 28-year-old David Trenchard, married without children.

The headline “The bongies dilemma and other crucial theological questions”

summed it up quite nicely.

The bishop had been hoaxed.

Beer and pink bikinis

A SMALL and selfless contribution to the cause, a couple of pints last Saturday in the recently troubled Cockfield Workmen’s Club, now happily out of liquidation. A fellow drinker recalls that I once put him in the paper. “It was Durham Big Meeting and there were a couple of Spennymoor lasses in pink bikinis. I said they’d catch their death of cold and you printed it.” Cold comfort, he’s in again.

AN old-times pint, too, with the splendid Tommy Taylor, a LibDem who represents Coundon on Durham County Council.

Inevitably the conversation turned to the night shift at Shildon wagon works, Tommy in the process of howking out his ear with a matchstick when someone inadvertently jogged his elbow, leaving half the implement inside his head.

Unable to be helped in the ambulance room, Tommy was taken to Darlington Memorial Hospital where the casualty officer proved sympathetic. “Ah, Mr Taylor,” he said, “are you still listening to the match?”

Poor Tommy wasn’t struck at all.

EVIDENCE of the party’s resurgence, perhaps, there’s also a call on his 81st birthday – St George’s Day – from Darlington LibDem councillor Peter Freitag.

Peter, also a leading member of the town’s Jewish community, finds himself paying rather more legal fees than he’d like just now and thus asks why you can’t circumcise a solicitor. The answer, alas, may not be provided in a genteel column such as this.

SINCE the column seems almost to have adopted Isaac’s Tea Trail up in the North Pennines, news of a ten-mile guided walk along part of it on May 22. The party meets at Isaac’s Well in Allendale at 10am, takes the bus to Nineheads and then hoofs back over terrain said to have some “short strenuous stretches”. Fare’s £4, advance booking required to the North Pennines AONB office on 01388- 528801. It’s all part of the North Pennines Festival of Geology and Landscape from May 22 to June 6.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article