A Domino Dinner in Thirsk, an interloper from north of the Tees and one or two loosened ties.

JUST as it has every March since 1915, the world’s oldest domino drive took place – top gear – last Friday.

Officially the Thirsk Gentlemen’s Domino Dinner, it began as a wartime morale booster – Tradesmen v Farmers – and has been knocking about ever since.

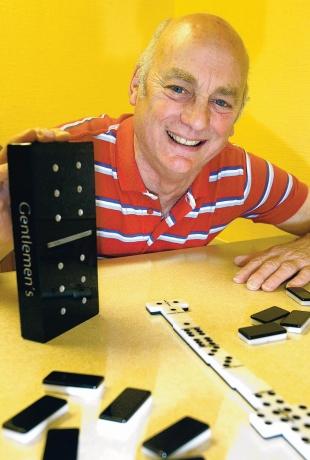

“I think at first there were quite a few gentry,” says Dave Gray, the organiser, surveying the seven o’clock setting. “Thirsk doesn’t have so many gentry now, so instead we have this lot.”

Little else may have changed, neither the insistence that it is strictly men only – “It’s a lads’ night out, some of them get quite excited about it,” says Paul Cowton, the defending champion – nor the fashion sense of some of the participants. Thirsk doesn’t do belt and braces, just braces.

Though the venue is the Golden Fleece, though the beer’s Black Sheep, the main course remains beef or beef.

For several years in the 1980s, however, the venue had changed to the Three Tuns, a couple of doors along the market place, after Fleece management committed a faux pas excellence.

They closed the bar early.

Now the Fleece once again embraces the annual board meeting, Dave Gray essaying a passable impression of the parable of the rich man’s feast by going out into the highways and hedgebacks and all but compelling them to come in.

“There used to be a waiting list, two or three years,” recalls Ken Green, a past winner. “It was a dead man’s shoes job, the Thirsk domino dinner.”

Thus it is that 46 sit cheerfully down last Friday, 45 good Yorkshire lads and an interloper from north of the Tees. A wrong ‘un may rarely have been more miscreant.

Because it’s Yorkshire, apparently, grace is said after the meal. Because it’s Yorkshire, there are battered boxes of “Imperial dominoes”

that may have been shuffling about when the map of the world was red.

The waitress is lovely, smiles a lot, fetches extra taties and gravy. She’s still not getting a game, though.

ONE of the problems with dominoes is that it doesn’t have a youth policy, nor even a middle-aged spread. Save for Dave’s son Pete, none may be under 50 and few not in receipt of the Queen’s shilling on pension day.

Another is that few can agree on the required level of skill. “Pure luck,” insists Paul Cowton. “Last year was my first time. I usually only play dominoes at Christmas and after the sixth pint of lager, I couldn’t even see the spots.”

Some are fives and threes men, odd numbers indeed, others domino driven.

It’s professionals against amateurs, says John McIntosh, a former winner. “We’re the professionals, the fives and threes men. When you’re playing these other fellers, you can’t work out what they’re going to do.”

There are even some, it is whispered, whose principal theory of successful domsmanship is to get shot of the highest first.

There are tables of four, 24 games, the first two moving on after each game. The last goes first; it’s a gentlemen’s do, after all.

Some play as if on Broadband, others like they’ve to dial 0 and ask for the operator. Some just want to talk.

Some of the resultant choreography makes Strictly Come Dancing look like the St Bernard’s Waltz.

The scene’s timeless, anywhere between 1915 and 2010; already they contemplate the centenary. “If you get 95 or 96 points you’ll probably win,” says Dave. “Sometimes the winners only in the low 90s.”

The victor gets a rather handsome marble double six – one of the regulars is a monumental mason – and around £20. There’s a booby prize, too, carefully wrapped. “I’m not saying, but it’s good for the complexion,” says Dave.

As if to emphasise dominoes’ intrinsically athletic nature, he carries the trophies in an All Sports bag.

It’s all hugely friendly, conversations ranging from chicken wire to quadruple heart bypasses, though one elderly chap’s talking about taking her up to Dalton Airfield for a good seeing to. Rather disappointingly, it turns out he means his motor car.

The serious, and the scumfished, have removed their jackets. One or two even loosen their ties. Most are steady away on the beer. One chap’s drinking coffee. There’s talk of having him blood tested.

It’s thus something of a surprise when the talk ambles around to the interloper, who at the halfway stage is not just in the lead, but with a score of 51 points – on target for a record.

What happens next may be the biggest fall from grace since Newcastle United, under Mr Kevin Keegan, led the 1995-96 Championship by 12 points and still managed to throw it all away. Grown men still have nightmares about that one.

Having won seven of the first 12 games, I fail to take any of the downward dozen but still manage 93 points, second place and a little brown envelope. I’ve always wanted one of those.

Tony Bardon has 99 points and the monumental masonry, professes himself amazed – “I’d love to say it was all down to skill, but I fear it’s all down to luck” – while Ivan Readman takes the booby prize for the second time. The first was in 1979 “I keep hoping I’ll get better,” he says.

A great night ends about 11. 45pm, half Thirsk about to turn into a pumpkin.

Just as it has every March since 1915, morale seems to have been boosted very significantly.

Memories of a mowdy man

LAST time I’d been in the Golden Fleece was in the convivial company of Bill Foggitt, meteorological maverick and celebrated mowdy man*.

Though a former Methodist local preacher, Bill could be found there most days. “An acquaintance buys me a pint, a friend treats me to two,” he once told a radio interviewer.

The Financial Times did even better. After a long interview, they asked Bill about a cheque. He suggested a pint a day for a year. Much to his surprise, they agreed.

He lived alone in Thirsk, based his forecasts on nature, achieved national fame in 1985 when the Met Office forecast a prolonged winter cold spell and Bill, having seen a mole tentatively pushing its snout skywards, decreed – after Mr Kenneth Grahame – that spring could not be far behind.

They remembered him affectionately at the gentlemen’s relish, too, recalled that the bottom of his trousers would forever be frayed because the dogs chewed them, spoke of the favourite old deerstalker that was carried into church atop his coffin. Bill died in 2004, aged 91.

Ken Green’s wife had worked as a receptionist at the Fleece, asked Bill – though the happy occasion was still many months ahead – for a wedding day forecast. “He said it would be wild and windy and he was spot on,” says Ken. “Mind, he said nothing about those damn great hailstones as well.”

*A mowdy, as they’ll tell you in rural parts, is a mole.

A twinkling star at 104

EARLY Tuesday was glorious in Wensleydale.

Though snow still painted Pen Hill, booted walkers positively gambolled in the sunshine, betting on a saving spring.

Dorothy Walker progressed a little more carefully. It was the morning after her birthday, her 104th, and there’d been two parties.

“I had to crawl upstairs last night,”

she said, though she insisted that she hadn’t had a drink. There were those with an eye on the metaphorical line on the brandy bottle, it should be said, who gently doubted that claim.

She is a quite extraordinary lady, though the last time we’d met – harvest festival, 2007 – not even the oldest in her small village. “Bellerby’s junior senior citizen”, the At Your Service column observed.

Beattie Tupling died last year. Mrs Walker flourishes, a bright twinkling star. Still she lives independently, still washes her own windows and at the age of 99 won £150 and some dog food – the dog food was never properly explained – in Take a Break magazine’s crossword competition.

The minister visits faithfully every Monday. “He does the clues I can’t,” she said.

“She’s also a huge fan of your columns,” wrote Alison Torode, inviting us up to Tuesday’s celebration coffee morning in Wensley village hall.

They baked beautifully – they always do – gave her yet more cards and presents. “You’ve made me very happy,” she said, and rose to make the little speech.

She came to Bellerby when she was 21, taught in the village school, met her husband at a dance – Bellerby of the ball, no doubt – played the parish church organ for 74 years, still loves music and remains a high-note regular at the Wensleydale Festival of Song.

Longevity, she supposes, owes much to trying to be happy. “I also love children, they’re so good, and I’ve had them around me all my life.”

The new village hall rather resembles a cricket pavilion, the spread fit for the Ashes. Officially it’s on Cuthbert’s Garth, because it was Cuthbert Kirkbride who gave them his grazing-land when they were stuck for somewhere to go. “There were only half a dozen sheep on it,”

he said.

Mrs Waker ate well, declined cake – “All caked out,” Ali Torode supposed – was asked how she’d be putting in the afternoon. She didn’t quite know. “I wonder,” she said, “if there might be a party.”

SIMON Egerton Scrope, head for 45 years of a family that’s been around since Norman times, has died. He was 75.

In the 300 years between Edward II and Charles I, said a recent history, the Scropes had provided one archbishop, two bishops, a Lord High Chancellor, two Chief Justices, four Treasurers, five knights of the garter, two earls, 20 barons and sundry others, peers and peerless.

Since 1548 they’d lived at Danby Hall, near Leyburn, devout Roman Catholics even at the time of recusancy.

“Danby Hall,” said Sally Doyle’s history, “became the heart of a small and secret community of Catholics in Wensleydale.”

Again on Sunday shift, we’d met him last year. Though too unwell after a back operation to have attended mass at the Byzantine church at Ulshaw Bridge, down the road, he kindly offered the guided tour – priest holes and all.

He’d supposed the recusancy laws to have been as unworkable as the anti-hunting legislation. “We’re being clobbered,” he said.

“It’s extremely difficult with the burden of taxation when you have land and you’re farming, but we’re very determined to keep it going.

“We’ve been persecuted, but we kept our heads down and got on with it. I expect that’s what we’ll do again.”

A private funeral will be held at St Simon and St Jude’s, Ulshaw Bridge.

A memorial service will follow later.

SOMETHING of which neither we nor his parishioners may have heard the last, last week’s column noted that the Rev Robert Williamson, vicar of St Cuthbert’s in Darlington, was a dab hand at playing the saw.

“Quite a few clerics seem to have many strings to their bows, or in Robert’s case teeth to their musical saws,” notes Paul Gilmore, from the Friends of St Cuthbert’s.

Among them is Christopher Wardale, now retired from the neighbouring parish of Holy Trinity, who’ll be at St Cuthbert’s tonight to give a talk on a thousand years of stained glass.

All are welcome, non-members £5 including wine, 7.30pm start.

…and finally, last week’s column ended with the thought that Tyneside playwright Ed Waugh would probably be galloping down the A1 towards East Layton, off the A66 west of Scotch Corner. Too true.

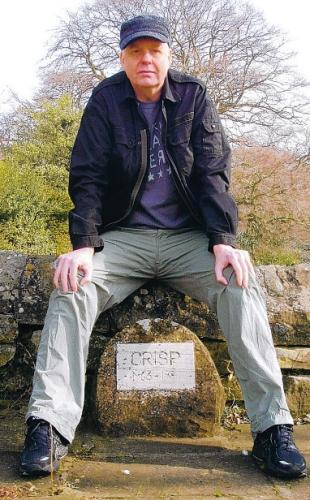

Ed’s written three comedies in which the central character has a thing about Crisp, narrowly beaten by Red Rum in the classic 1973 Grand National. He’d sought the column’s help in finding the horse’s resting place.

After retiring, Crisp spent eight years hunting around East Layton with Captain John Trotter and is buried beneath a horse chestnut in the village.

Ed duly went down to pay his respects.

“The captain was a very nice chap,” he says and here, Waugh record, is evidence of the visit.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article