IT’S 9.15 on Sunday morning, but the carrot-smart kids are in their weekday best, awaiting the VIP visitor to their school.

A little posse of churchwardens – a staff of churchwardens, as previously we have suggested – forms an honour guard, too.

“We never really thought that you’d come,” someone says to Dr John Sentamu, Archbishop of York, as he advances, grinning, towards them.

“Oh ye of little faith,” ripostes Dr Sentamu, and at once is consumed by a laugh that might register 8.5 on Richter. There was never an archbishop like this one.

His presence is improbable, nonetheless. Dr Sentamu is titularly Primate of England – the Archbishop of Canterbury is Primate of All England – and East Cowton is but a one-pub, one-horse village between Darlington and Northallerton, marking the centenary of its parish church.

“There was a sort of feeling of let’s give it a try, you never know,” says the Reverend Alan Glasby, team rector of a dozen or more churches thereabouts.

It’s a lovely spring morning, East Cowton blessed not just by Dr Sentamu’s visit but by being the base for a cycle event apparently organised by the Ferryhill Wheelers.

The lady of this house doesn’t much care for the Ferryhill Wheelers since an incident a few years back, though her exact observation may not be repeated in the church column or, indeed, in any other.

Also among the welcoming committee is the Reverend Andy Nicholson, a priest once described hereabouts as resembling a British light middleweight boxing champion.

Andy reveals that he’s also a Freeman of York on his grandfather’s side, prompting a brief debate on whether a Freeman takes precedence over an archbishop.

“If he has any sense,” says Alan Glasby, “he’ll let the archbishop go first.”

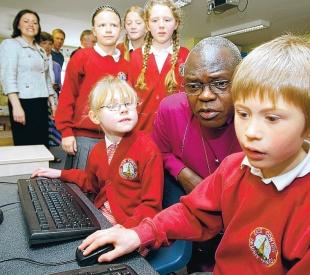

Like an archiepiscopal pied-piper, the bairns also follow the purple-clad archbishop round to the back of school, where he is to open new facilities.

A small voice is heard to ask if it’s really true, that they can go home again at ten o’clock.

He’s assured that it is. Oh ye of little faith.

BUILT in 1978, the school is celebrating the completion of a new outdoor area, an extension to one classroom and refurbishment to another.

There are 48 pupils.

Archbishops would once have declared it formally open. Dr Sentamu announces that they have lift-off.

Back in the school hall there’s a short service, the blessing of a cross given by the churches of the parish, a chance for the archbishop to tell a story about the two monkeys and to play the drums. He’s a dab hand at the drums.

Julia Campbell, the head, talks of the culmination of four years’ hard work and commitment and of how strange it seems to be in school on Sunday morning.

The school’s mission statement – everyone should have one – is simply “The possibilities are endless”.

In other words, says the head, nothing in life is impossible if you really want to do it.

Not even getting the Most Reverend and Right Honourable Archbishop of York to play the drums in the school hall at East Cowton.

LED by his chaplain, Dr Sentamu assumes full fig for the procession from school to church.

“There’s posh,” says one of the wardens.

“What did you expect?” asks the archbishop, and laughs like a penny machine on the end of Blackpool pier.

It’s like a royal visit without the Special Branch, not even a country policeman to keep apart Ferryhill Wheelers and East Cowton kneelers.

Dr Sentamu stops at the village shop, gently to chaff the lady inside for buying chocolate on a Sunday. She doesn’t give him a bit.

Consecrated at York in November 2005, he will be 60 in June, simultaneously giving an impression of energy, enthusiasm, endeavour and enjoyment.

The single word may be charisma; even the photographer thinks he’s great.

Those who know photographers, an oft-times querulous crowd, will know what a compliment that is.

All Saints’ foundation stone was laid on July 8, 1909, by Louisa Pulleine, wife of the Bishop of Richmond – who himself had been taught at East Cowton vicarage.

The previous church had been outside the village, described in contemporary reports as dingy, cramped and other unflattering things and in The Northern Echo, a little more charitably, as inadequate. The new one was on land given by Lady Chermside.

On that day almost 100 years ago we also reported that a body had been found, tied hand and foot, in a reservoir between Frosterley and Middleton-in-Teesdale, that the north Durham village of Swalwell had been en fete to welcome home jailed miners – we didn’t say why they’d been imprisoned – and Jesse Ross, described as “the Crook cyclist”, had died in Stockton hospital after a collision with one of those new-fangled motor cars.

The church is full, the music splendid, the mood merry. The archbishop talks in his sermon of a frightening world, and how fear exaggerates things.

“There isn’t an ounce of fear in Mrs Campbell. Because she hasn’t got fear, the school is being turned around.” He has clearly taken a shine to Mrs Campbell.

It’s a lovely, lively service followed on the lawn out the back by a lovely, lively lunch. The archbishop’s everywhere – booming, beaming, unabashed.

By 1pm hardly anyone has gone home, and certainly not the purpleclad iconoclast. He’d warned them, those of little faith and of more, what would happen if they took no notice of his sermon.

“If you don’t,” said the improbable VIP, “I’ll be back.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article