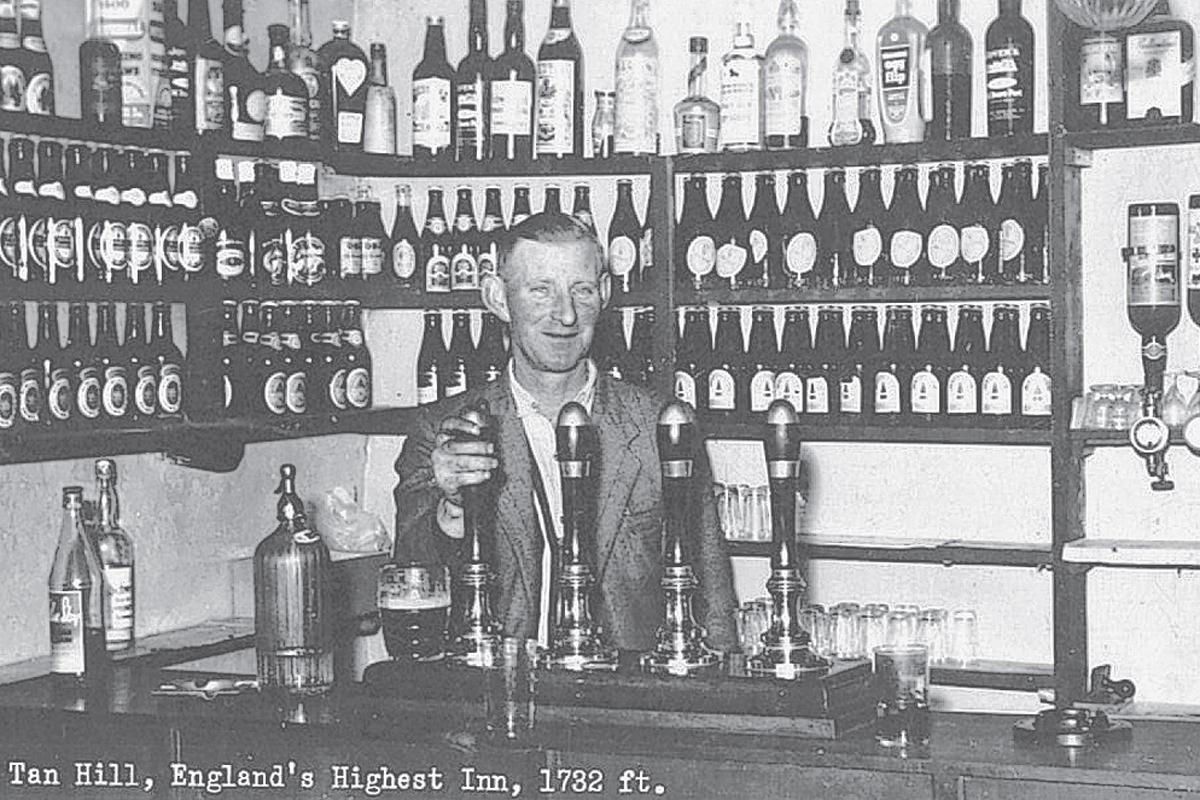

The Tan Hill Inn is Britain’s highest pub. In a new book Neil Hanson, who was landlord of the windswept hostelry in the late 1970s, serves up tales of endless disasters, extraordinary locals and late-night lock-ins

ONCE upon a time, not so long ago and not so far away, a young man and his wife were living a quiet life in a tiny Yorkshire village; I know because I was that young man. It was 1978, an era when shops shut on Saturday lunchtime and didn’t reopen until Monday morning, olive oil was obtained from chemists and used, not for Jamie Oliver recipes, but for dissolving earwax, and the only exotic spices in general use were salt and pepper.

I was beginning my career as a freelance writer, and so spent every morning drinking endless cups of coffee and reading newspapers. Just when I was finally thinking seriously about starting work, our dog would place her chin trustingly on my knee, her dark brown eyes would meet mine and I’d decide to “just take the dog for a quick walk, before really getting down to it”.

Several hours later, we’d return from an exhilarating ramble over the moors, leaving me just time to towel the dog clean of incriminating mud and peat, crumple some sheets of paper and scatter them around my desk and sit down at my typewriter – personal computers hadn’t been invented then, or if they had, the news hadn’t reached me – before my wife, Sue, returned from her genuinely hard labours.

One morning, however, I came across a newspaper article about the search for a new landlord of the highest inn in Britain. It was also the most remote, high on the Pennines with only sheep and grouse for company, for its next-door neighbour was four miles away.

The wind was so ferocious – “strong enough to blow the horns off a tup (a ram)” – that it could rip car doors from their hinges and force would-be customers to enter the pub on their hands and knees; for reasons unconnected with wind and weather, there’s never been a shortage of customers leaving pubs by that method. It rained 250 days of the year – on the other 115 it was probably drizzling – and in winter it was cut off by snowdrifts for weeks on end. There were no mains services, just a generator for electricity, a radio telephone and a spring for water.

“Only a complete idiot would want to run a place like that,” I thought, dialling directory enquiries.

Seven days later, having already climbed more mountains and crossed more dales than Julie Andrews ever managed in The Sound of Music, we found ourselves driving up an apparently endless hill with wind lashing the surrounding barren fells.

“We must have missed it,” I said.

“Even Heathcliffe wouldn’t live up here.” But right at the top of the hill, we found the highest pub in the country. It also looked like the ugliest, with collapsing render, cracked windows, and flaking paintwork; “The Slaughtered Lamb” from An American Werewolf in London, came to mind, though admittedly with fewer psychotic customers.

If the inn was – to put it mildly – disappointing, its surroundings were absolutely breathtaking: a rolling ocean of moorland, stretching to the horizon in an endless tapestry of subtle colours and textures, all arrayed beneath a vast cloudscape that was never the same for two seconds together. We stood there transfixed; it was love at first sight.

Inside the inn, the walls were black with damp, water dripped steadily on to a sodden carpet and we could hear rats scuttling across the ceiling. ‘What’s that noise?’ I innocently asked one of the owners.

“Oh, I think a pigeon’s got trapped in the loft,” he said shiftily. “Divvent worry son, I’ll pop up later and have a look.”

Both he and his partner looked about as straight as saplings in a Force 10 gale. We sat round a table, eyes watering in the smoke from the smouldering fire, while they read my CV, in which I’d attempted to prove that freelance journalism was not only a suitable background for a landlord, but practically essential. They asked a few questions and then said “Righto then son, we’ll be in touch”.

“And our expenses?” I said – you can take the man out of journalism, but you can’t take journalism out of the man.

“We’re not paying expenses,” they said, with almost indecent haste. “It wouldn’t be fair on the others.” “The others?”

“The ones who don’t ask for expenses.”

On the journey home, we considered whether to accept the job, if it were offered. “We’d be giving up a pretty near idyllic existence,” Sue said. “We’d have to be mad to swap it for a cold, wet, windy, rat-infested ruin in the middle of nowhere.”

“So that settles it, then,” I said. “If they offer it, we’ll take it.”

The result of that folie a deux was that a week later, in the grip of something as powerful and illogical as the lemming’s desire to see what’s over the next cliff-top, we found ourselves behind the bar of the Inn at the Top.

Over the following years we met extraordinary characters, had laughs – and a few tears – and experiences that we’ll never forget. The Inn at the Top is the story of those times.

There’s no pub called The Inn at the Top of course, I’ve changed all the names, to protect the innocent (and myself from lawsuits!) but if you know the Dales, I’m sure you’ll recognise it. And if you watch the original Everest double glazing ad on YouTube, featuring Ted Moult and his famous feather at a windswept inn, you’ll see a remarkably young-looking, dark-haired landlord pulling pints behind the bar... how things have changed, in every way, since then. Extracts from

The Inn at the Top:

Yow what?

“You’re the new ’uns then?” he said. “Last lot didn’t stop so long, did they? Any road, let’s see if you can pull a pint, shall we?” He watched me fill his glass and then paid his money, showing no reaction to the locals’ discount I gave him, then paused and gave me an appraising look. “Nah then, lad, dost tha ken Swardle yows?”

“Pardon?”, I asked.

“Thought so,” he said, stumping off to announce to a group of his peers in the corner that some offcomer with ‘plums in his gob’ and a total ignorance of the Dale’s trademark breed of sheep had taken over the pub.

Lightning strikes

FRED and his fireplace were clearly accident-prone, because a few months later he was poking the fire during a thunderstorm when a lightning bolt struck the field at the back of his house. Since the fire had a cast-iron back boiler and the poker was touching it when the lightning struck, Fred became his very own lightning rod and was blown right across the room. When he came to his senses, he was sprawled against the far wall, but apart from a burn to his hand and a buzzing in his ears he was unharmed, and he was certainly in sparkling form – quite literally – in the pub that night.

Licensing hours

ONE Sunday night during his time at the inn, Fremmy had presided over one of the most notorious lock-ins ever staged there, interrupted by a police raid that netted the impressive total of 64 after-hours drinkers. It says much for our own cavalier disregard for the licensing laws that we took that figure as a challenge – a UK all-comers’ record that was just begging to be broken. Although our official licensing hours remained 11 to 3 and 5.30 to 10.30, our doors were open non-stop from seven in the morning, when the hikers ate their breakfast before striding off over the moors, until two o’clock – and sometimes even later – the following morning, when the last reluctant farmer was finally propelled through the door.

Phlegmatism

THE inhabitants of the Dale all tended to display a similarly lugubrious fatalism to events great and small, as stolid and indifferent to the problems of the world outside as it had largely been to theirs. Had Orson Welles’ version of War of the Worlds been set in the Dale broadcast on local radio there, it is unlikely to have had quite the same impact on these phlegmatic people as it did on the population of New York.

“Sad weather, Stan.”

“Aye.”

“I see the Martians have landed, then.”

“Aye.”

“Aye. Well. Happen they’ll be wanting a few yows.”

“Happen they will. Any road, best be having the one we came for, eh?

Two more pints, please, Doris.”

What’s in a name

IT was one of hundreds of inns that once stood in remote and lonely places, usually at a crossroads of two moorland tracks, greenways or driftways.

The Inn at the Top’s name derived from the Old English word for a branch in a track or from the Celtic word for fire, either because of the coal that outcropped there or because the hill on which the inn stands was one of the sites of the symbolic fires that the Celts lit at their great festivals to commemorate the changing of the seasons: Samhain at the start of winter and Beltane to herald the summer.

Dangerous territory

IT had come on bad that night, and like a fool, I had got myself lost. I could hardly see for the snow or hear for the shrieking gale and it was only by the greatest good luck that, after a few of the most anxious minutes of my life, a brief lull in the wind allowed me to hear the dull thud of the diesel engine of the generator behind me. I turned around and, with the dog at my heels, found my route back to the sanctuary of the inn. I had already walked right past it without realising it and was some distance away and heading out towards the open fell.

- The Inn at the Top (Michael O’Mara Books, £8.99)

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here