STUART Maconie spotted that an approaching major anniversary that was attracting little attention. In his words there were “no hashtags, no videos, no campaigns... It was not going viral.”

The upcoming landmark was the 80th anniversary of the Jarrow March – October 2016. Maconie was dismayed that it “was not trending…We had not reached peak Jarrow, or anything like it.”

Happily, Maconie noticed this neglect in time to pay his own tribute. He literally took steps – hundreds of thousands of them – to put it right. He resolved to “retrace the walk day by day as the marchers did, visiting the same towns and comparing the two Englands of then and now.”

Maconie reports on his ambitious personal homage in Long Road from Jarrow (Ebury Press £16.99). He had travelled a mere 12 of the 291 miles when a café waitress in Chester-le-Street, to whom he had confided “I’ve walked from Jarrow; I’m retracing the Jarrow March,” replied: “Oh have you. Very good. That’ll be £2.65. I’m locking up in ten minutes.”

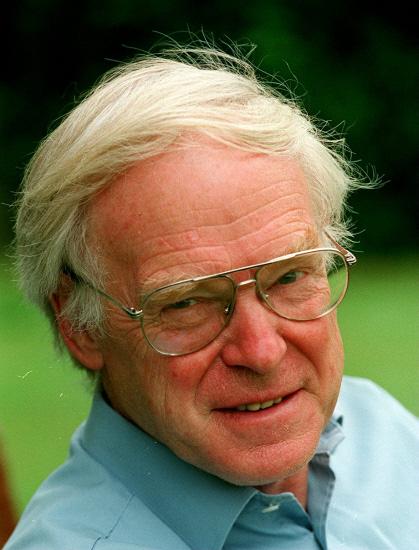

Perhaps best known for the afternoon BBC Radio 6 music show he presents with Mark Radcliffe, Maconie offers many such seemingly unconsidered yet often revealing trifles. And you can never second guess him. He confesses, nay proclaims, a fondness for the Chuckle Brothers, only narrowly foregoing an opportunity to catch their act in Leeds, in favour of an evening of classical music.

At his previous stop, in Harrogate, he’d sampled his first Wetherspoons. Cue for sniffy disdain? Not so. “I liked it. It was full, and not of slavering beer monsters as I’d been led to expect, but of cheery, civilised working people having a pint and a meal after work.”

Maconie recalls that both Harrogate and Ripon, though staunchly Conservative, had warmly welcomed the marchers. Like that café waitress, Chester-le-Street had been pretty much indifferent – perhaps, thinks Maconie, out of resentment that Jarrow had seized the initiative.

Northallerton was frosty: no official reception and not even a single rebel councillor to shake their hand. “The council would not allow them to sleep in any council-owned building so they took cold and uncomfortable shelter in the drill hall,” recalls Maconie.

He himself fared rather better, especially when he found himself in The Little Tanner - “one of those strangely likeable new pubs or bars that have sprung up all over Britain in what feels like front rooms or old sweet shops or printers.” Its patrons, he reports, were “luxuriantly bearded graphic designers wearing vintage US seed-merchant baseball caps and drinking botanical gins and Sri Lankan pale ales.” The Northallerton more recognisable to most who know it was summed up in a comment to him: “They say round here that in Northallerton they’d vote for a pig if you put it in a tweed jacket.”

As he journeys, Maconie discovers knowledge of the Jarrow March is patchy. One man who gets most of the facts right places the walk in 1926, year of the General Strike. In response to a progress report that Maconie posts on the internet, someone from Kent tweets: “Who cares. The world’s moved on.”

Himself a Northerner, from Wigan, Maconie says that Jarrow now conveys “no sense of a town cowed or beaten.” In the town today “you can buy cupcakes and smoothies”.

And yet, “there is still the faint echo of neglect and decline, and none of the easy, comfortable atmosphere of content that I’ll increasingly find as I travel south.”

Perhaps the closest echo of the March, or what led to it, came in Darlington. The Quaker House pub was running an anti-austerity WSO (We Shall Overcome) weekend. The landlady explained to Maconie: “There are 260 WSO gigs going on across the country but there has been no press coverage. Help spread the word. We want food for the food banks, sleeping bags for the homeless. Darlington has been massively affected by ‘austerity'.”

Shockingly if unsurprisingly (for neither the Labour party nor the TUC backed the Jarrow March) Parliament virtually ignored the marchers. Once handed in, their 10,000-signatures petition was never seen again. Its whereabouts remain unknown.

But Maconie was welcomed into the Commons by Batley and Spen Labour MP Tracy Brabin, who succeeded the murdered Jo Cox. “Are we not on the verge of Jarrow again?” she rhetorically asked Maconie. “Batley food bank has given out 8,000 meals.”

Maconie’s long road persuaded him: “Brexit proved there is not one England. We are not all in this together, and in that we have much in common with the fractious and divided 1930s.” But he adds: “I’m not sure I want a nation entirely at ease with itself.”

That, he suggests, hasn’t been Britain’s way.

“We’ve cut the heads off kings and taken axes to each other in the streets and pastures…Better a nation always arguing amongst itself civilly but passionately and endlessly restless in brilliant, angry, loving, vital cities and hard, defiant little towns, in market squares…”

Perhaps his key word there is “civilly”, which some might say is diminishing to vanishing point. But Maconie has painted an absorbing, entertaining picture. He writes: “Britain in 1936 was a land of beef paste sandwiches and drill halls. Now we are a nation of vaping and nail salons, pulled pork and salted caramel… I looked it in the eye from morning to night and never grew tired of it. I hope I have done it justice.”

Readers will enjoy making up their own minds.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel