Echo Memories looks at the life of Henry Hardinge, who bought his way into the Army and rose through the ranks all the way to the very top.

It was noted in last week’s Echo Memories that one of Durham School’s old boys was Henry Hardinge, a hero of the Napoleonic Wars who rose to become head of the British Army, Secretary of State for War and Governor-General of India. His story is fascinating.

THE Hardinges were a wealthy and well-connected family both socially and politically, and Henry was not their only bright star.

Born on March 30, 1785, at Wrotham, in Kent, he was the grandson of MP Nicholas Hardinge, Secretary of the Treasury and Clerk to the House of Commons, and the third son of the Reverend Henry Hardinge, the Rector of Stanhope, in Weardale, then an extremely wealthy living, worth £5,000 a year.

The young Henry was brought up at Sevenoaks by two maiden aunts and, on leaving Durham School, joined the Army when only 14, a not unusual event at a time when commissions in the British Army could be and frequently were bought.

His first posting in 1799 was to Canada as a member of the Queen’s Rangers where, with the rank of ensign – second lieutenant in today’s terminology – he was responsible for carrying the unit’s colours.

Within three years, he returned to England, where he bought first the rank of lieutenant in the 4th Regiment of Foot, then transferred to the 1st Regiment of Foot – the oldest infantry regiment in the British Army – until, in 1804, he bought a captaincy in the 57th Foot.

Although it may seem strange by today’s practices, with this experience under his belt, he was admitted in 1806 to the Royal Military Academy, which had been at High Wycombe since 1799 and was a predecessor to Sandhurst.

In 1807, having spent 18 months there and passed the required examinations, he was posted as deputy-assistant quartermaster-general to Portugal, leaving Portsmouth in December to travel via Gibraltar and Cadiz to join a force in Portugal under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, later created Duke of Wellington.

The Peninsular War had begun in 1807 when Napoleon Bonaparte had moved French troops into and through Spain in order to invade Portugal, but he then deposed the Spanish king so he could put his brother, Joseph, on the Spanish throne.

The British, Spanish and Portuguese became allies against the French, with Wellesley first defeating the enemy at Rolica in August 1808.

Henry Hardinge was part of the victorious army.

Four days later, while with Wellesley at the Battle of Vimeiro, he was badly wounded and when Wellesley returned to England, he came under the command of Sir John Moore and was beside him when Moore was killed during the Battle of Corunna in January 1809.

Moore’s burial soon became part of popular English literature in the poem by Charles Wolfe: Not a drum was heard, nor a funeral note, As his corse (corpse) to the rampart we hurried; Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot O’er the grave where our hero we buried.

Slowly and sadly we laid him down, From the field of his fame fresh and gory; We carved not a line, and we raised not a stone, But left him alone with his glory.

In 1809, Henry Hardinge became a major and, two years later, lieutenant-colonel and deputy quartermaster-general of the Portuguese army.

He took part in most of the battles of the Peninsular War and, following Wellesley’s return to the peninsula, played a significant part in the outcomes of most of them, being again very badly wounded at the Battle of Vitoria, but forcing himself to be sufficiently fit to lead his brigade at the battles of Orthez and Toulouse.

Following the defeat of the French, Hardinge was transferred to the 1st Regiment of Foot, which later became the Grenadier Guards.

He was knighted in 1815 and when Napoleon escaped from the island of Elba, it was Hardinge who was sent by Wellington to observe what he was up to.

At the Battle of Quatre-Bras in 1815, Hardinge’s left hand was so badly damaged that it had to be amputated at the wrist, an injury that meant he was not at the great Battle of Waterloo.

He did, however, receive a memento of Waterloo when Wellington gave him Napoleon’s captured sword as a gift.

Three years later, the Duke presented him with a sword of honour.

In 1820, Sir Henry Hardinge’s career took a new turn when he stood for Parliament and was elected Tory MP for Durham.

He was also made a full colonel and, in December 1821, married Lady Emily Jane Stewart, daughter of the Marquess of Londonderry.

Between 1823 and 1827, Harding became clerk of the ordnance, making significant improvements to a number of areas of army life.

He retired from active service in 1827 and a year later, with Wellington as prime minister, became secretary at war.

While holding that office, he stood as a second for Wellington in a duel against Lord Winchilsea.

In 1830, the year in which he was promoted to major-general, he ceased to be secretary at war and, after ten years in the seat, changed his constituency from Durham to St Germans, in Cornwall, but only briefly because in 1831 he transferred to another Cornish seat, Newport, and from 1832 to 1844 was MP for Launceston, also in Cornwall.

Between 1830 and 1835, during the reign of King William IV, Hardinge was chief secretary for Ireland twice, despite it being a role he did not want, but was prevailed upon to accept.

From 1841, when he became a lieutenant-general, until 1844, he was again secretary for war until being appointed in 1844 Governor-General of India, an appointment, sanctioned by the young Queen Victoria, which he held until 1848, when he retired at his own request.

With most people, Sir Henry Hardinge was never unpopular during his entire illustrious career and went to India with a name for being honest, just, uncomplicated, considerate and upright.

To those qualities must be added his immense capacity for hard work.

Within two weeks of his arrival in that vast country and characterised by Sir Robert Peel as being “by far the best man” for the job, he was hard at work as usual, giving his attention first to issuing friendly warnings to troublemakers in the area of Oude.

He made it illegal for anyone to have to work in government departments on Sundays and devoted much time and extensive resources to improving the quality of education across the country.

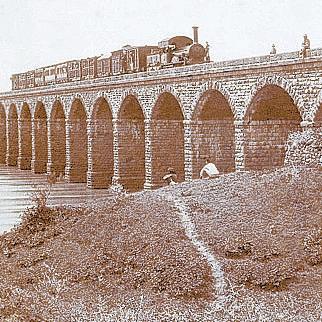

Perhaps the greatest contribution he made to Indian life was that, having recognised the value railways could make to economic and military life, he advocated their introduction into the country. Work on the first of them, at Bombay, started in 1850, two years after his return to England.

In the first year of his Indian service, he doubled the size of the British garrison along the north-west frontier so that when the first Sikh War broke out in 1845, a ferocious affair, there were enough men and munitions in the right place to fight the conflict, which ended only three months after it began.

Hardinge had himself led part of the army.

With the war behind him, he visited one of the projects to which he had given a lot of his energies, the Ganges Canal, and did a great deal to introduce tea-growing into India.

In 1846, during his time in India, he was created Viscount Hardinge of Lahore and Durham, retiring with annual pensions of £3,000 from the British government and £5,000 from the East India Company.

He had remained in India longer than he had wanted to and gave up his post – in a much more settled country than he had found when he had arrived there – in January 1848.

Then aged 62, he worked again on the problems troubling Ireland and went on to apply his expertise to the strategically-important matter of Britain’s coastal gun batteries, which he caused to be improved with more powerful guns, convinced that, with the advent of steamships, the threat of a French invasion was not yet over.

Following the death of the Duke of Wellington in 1852, Viscount Hardinge succeeded him as commander-in-chief of the British Army and, in 1855, he became field-marshal.

He worked well with Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, who encouraged Hardinge to introduce the Lee-Enfield rifle and better small-arms as standard Army issue, to improve Army training at such venues as a permanent camp to be created at Aldershot.

One of the misfortunes of his life was that he was blamed by a board of inquiry after the Crimean War for some of the lack of preparations of the forces sent to fight there.

He found it difficult to suffer what public criticism was levelled at him.

While accompanying the queen on a visit to Aldershot in July 1856, he suffered a stroke and died in September that year.

It seems a pity that Henry Hardinge is not better-remembered today.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here