In April, The Northern Echo was invited to send a journalist to interview Sir Bobby about the launch of his charitable foundation. Owen Amos grabbed his notebook, but not his sense of direction, and went along for one of the most unforgettable hours of his life.

‘HELLO,” I said. “I have an appointment with Sir Bobby.”

The receptionist – female – looked baffled. Poor lass, I thought. Never heard of him. Still, that’s girls for you.

“Sir Bobby Robson?” I said. “The football manager.

I’m a journalist. I’m interviewing him here, at 1pm.”

“Are you sure it’s today?” she asked.

Yes, I said. Monday, April 28. I’d been looking forward to it. For journalists, interviewing world-famous football managers makes the parish council meetings worthwhile.

“Are you sure it’s the Malmaison Hotel?” she asked. Yes, I said. I checked my diary anyway, for proof.

And there it was: “Sir Bobby interview. 1pm. Copthorne Hotel.”

Deep down, the minute I met the receptionist, I’d known my mistake. Every North-Easterner knew Sir Bobby. Even girls.

I gasped an apology, dashed out of the lobby and looked at my phone. 12.58pm.

I sprinted along the quayside, one hand on my bag, one hand on my flapping jacket. I’d ironed it especially, as well.

It was raining, for a change: big, fat drops you can taste. I was panicking; blushing, though no one knew. Flustered and frayed, I reached the Copthorne and ran upstairs to the conference room. I wiped my brow and entered. It was 1.04pm. I could hear my pulse pumping.

Neither Sir Bobby nor his assistant looked pleased.

Well, would you? You expect to be interviewed by a journalist. Instead, one of the world’s finest football managers was staring at a hot, panting, drowned rat. A late drowned rat, at that. It was hardly Bashir meets Diana.

I needn’t have worried. An hour later, Sir Bobby was squeezing my knee, patting my arm, darting from Eindhoven to Ireland, and everywhere in between. He fizzed like potassium in water.

When I bade farewell, and checked my phone, it was 2.02pm. We’d overrun by 32 minutes. In reception, I saw Look North’s team – booked in for 1.30pm – waiting patiently. When you get Sir Bobby talking about football – we weaved from Roy Keane’s buys at Sunderland to James Milner’s future at Newcastle – don’t expect to leave on time. To him, it was another football conversation. To me, it was one of my best hours.

IWAS there to talk cancer, not football. Problem is, when a football-mad lad meets the former England, Barcelona and Newcastle manager, it’s hard not to. It was like a bowl of jelly babies on your desk: you can resist it for ten minutes, but, every so often, you have to dip in.

We did talk cancer, though. We talked of his first cancer, diagnosed in 1992 while managing PSV Eindhoven.

“It didn’t bother me too much because I have a strong mentality, a strong head,” he said. “I knew I was in capable hands.”

We talked of his second cancer, at Porto in 1995, which was worse.

“I got the shock of my life,” he said. “I had no symptoms, no swelling, no nothing. I was getting my sinuses cleaned out.

“They took some muck out, did a biopsy and told me I had a melanoma. They said it was very rare, and it shocked me.”

The operation – pretty gruesome, he said – involved his mouth and face being cut.

“The doctor said ‘Have you got any money?’ I said a bit, and he said ‘Good. Most people with this problem retire’. They said take at least six months off, come back in January. I was back by October.

“I was bored after three months out. I wanted to go back. My football was more important than cancer.

“Cancer will kill you, but I couldn’t live without football. I needed the game.”

Not everyone shared his optimism.

“A couple of years ago, I spoke to the surgeon who operated in 1995,” Sir Bobby said. “He said ‘We thought you would be dead in a year and a half’. Well, I’ve had 13 years since then.”

By now, the smile, the spark, was back. At first, he seemed old. His face was lopsided – because of illness – and his suit seemed too big.

Twenty minutes later, he was bigger, brighter, and younger, like an inflated balloon.

His great love – more than football – was life. Living it, and reliving it, rejuvenated him. The only one struggling to keep up was the journalist, 51 years younger, sitting alongside.

In 2006, Sir Bobby fell while skiing. The x-ray showed a shadow on his lung. The cancer, his toughest opponent, was back.

“If I hadn’t had that accident, I wouldn’t be here today,” he said. “Someone up there was looking after me.”

But, I asked, he must feel cursed. Three cancers in 11 years? That’s unfair.

“Not really,” he said, smiling. “I never thought I’d have such an active life, be on the pitch for more than 50 years.

“My life has been exhilarating. I’ve been a lucky guy – a very lucky guy.

I say ‘I’ve been in the game 50 years, I’ve had amazing health’. My wife says ‘Amazing health? You’ve had cancer five times!’”

In 2006, Sir Bobby had a brain tumour removed and, last year, his lung tumour returned. Despite ongoing chemotherapy, cancer didn’t affect him most. After his brain operation, a haemorrhage left him partially paralysed down one side.

“My driving has gone, golf, tying my shoelaces, doing my garden,” he said, more slowly, and glumly. “That has been almost worse than the cancer.”

But Sir Bobby, of course, had an extraordinary life, and wouldn’t deal with cancer in an ordinary way.

After Dr Ruth Plummer asked if he knew anyone who could raise cancerfighting funds, he spoke to his wife and secretary, formed a committee, and the Sir Bobby Robson Foundation was born.

It aimed to raise £500,000.

It did so by May, and keeps going.

‘WHERE’S that letter?” he asked his secretary.

The letter was found: from a 13-year-old girl, written on Winnie the Pooh paper, telling Sir Bobby she asked friends and family to not buy her birthday presents, but donate to the foundation instead.

“I found that letter so touching, most sincere,” he said.

“That’s what love and warmth and care is about.

It’s a lovely letter and it made me very proud.

“It’s about the £5, £10, £20 donations – the money from Betty, Johnny, Harry – from normal generous people.”

I loved the reference to “Betty, Johnny, Harry”. I imagined that, growing up in Langley Park, his neighbour was called Betty, his pal was called Johnny, and his uncle was called Harry.

Because, to Sir Bobby, “Betty, Johnny, Harry”, meant normal, North-East people, like him. Yes, he’d worked round the world. Yes, he’d more money than most.

But he remained a County Durham lad. He remained a Betty, Johnny, or Harry.

The girl’s letter rejuvenated him. Talking of paralysis, and battles with shoelaces, distressed him. He shrunk into his suit; slumped in his chair. Once Winnie the Pooh was out, he was upright, eyes gleaming.

He loved life, you see.

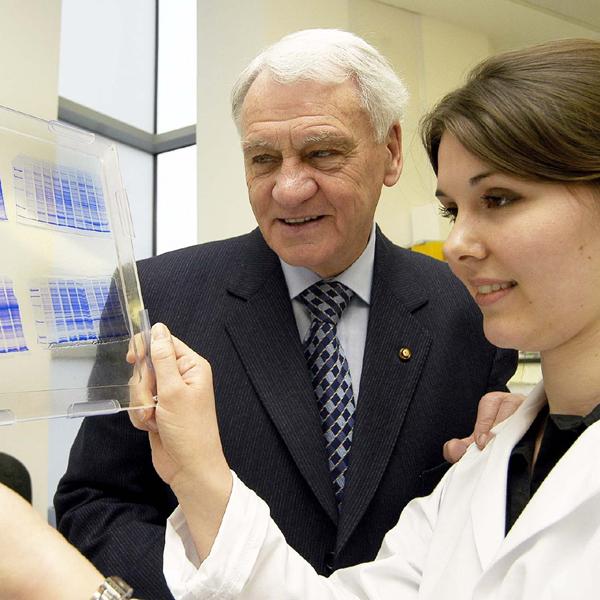

Before I left, I asked for a picture. Of course, The Northern Echo has hundreds of file pictures of Sir Bobby.

But I wanted a picture with the ex-England manager. It was that bowl of jelly babies again. Hard to resist.

His illness meant he stayed seated in the interview. For the photo, he said he’d stand. “No, stay sitting,” his secretary said.

“No,” Sir Bobby said. “I’ll be fine.”

Pictures taken, I asked how he’d like to be remembered. “Just as a proper person,” he said, after much thought. “A proper person who worked hard and did his duty to football.”

Langley Park, the North- East, England, and the world, will remember him as much, much more.

£500,000 raised for new unit

THE initial £500,000 raised by the Sir Bobby Robson Foundation is being spent on a 12-bed unit with treatment rooms, a laboratory and consulting facilities, which is being built at Newcastle’s Freeman Hospital.

It will be called The Sir Bobby Robson Cancer Trials Research Centre, and it will trial new drugs.

Once the foundation has raised sufficient funds to set up the centre, all additional money will go towards cancer-related projects in the North-East.

TO DONATE

VISIT the website, sirbobbyrobsonfoundation. org.uk, or send a cheque payable to the Sir Bobby Robson Foundation to:

The Sir Bobby Robson

Foundation

PO Box 307

Heaton

NE7 7QG

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here