Echo Memories takes a stroll, and learns the history behind the sights of Durham's city centre.

TWO of Durham's most famous buildings, its cathedral and castle, stand high above the River Wear, which has cut out and almost surrounds the peninsula from which they have stood sentinel over the city for more than 900 years.

At this spit of land's narrowest point stands the market place - established there, along with a new church, by Bishop Flambard early in the 12th Century to replace a market that had operated on land between the cathedral and the castle, known today as Palace Green.

The location of the old market had been a strategic liability because, although it was at the heart of the city's defences, it was accessible to everyone, citizens and outsiders alike.

At a stroke, Flambard closed that loophole, gave the traders a more convenient place to carry on their business and dedicated the new church to St Nicholas, patron saint of merchants.

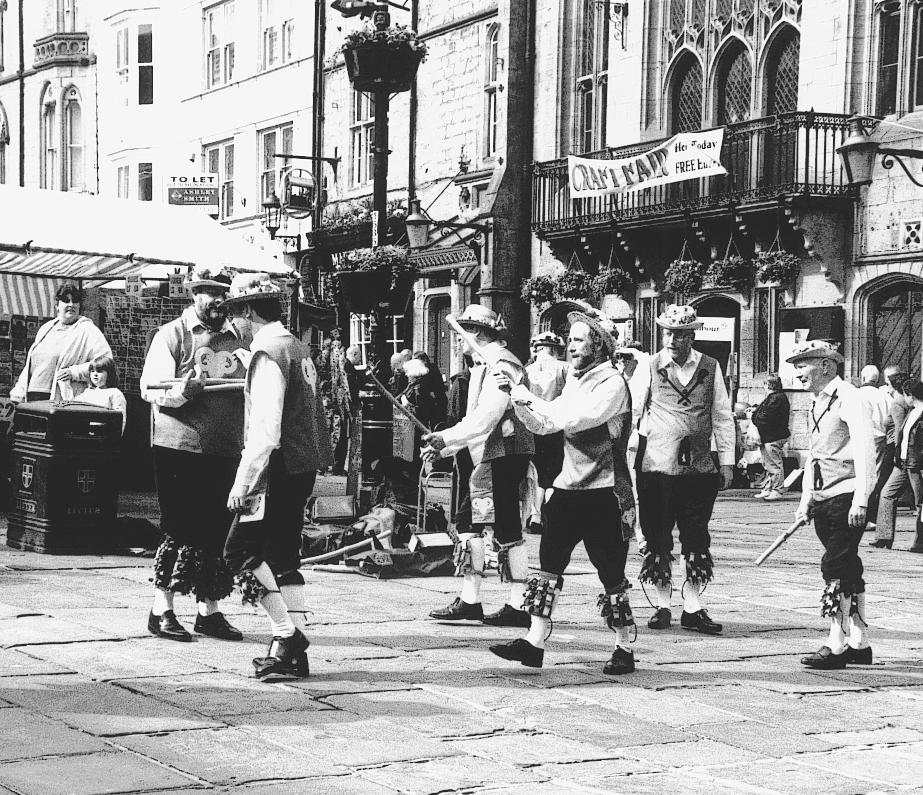

The regulation of trade in Durham, as in all large mediaeval English towns and cities, was rigidly controlled and enforced by the various guilds that controlled every aspect of their operation.

These guilds, jealous guardians of their considerable privileges, were established to oversee and guarantee the maintenance of high standards of workmanship in their crafts and to ensure - as far as possible - a monopoly of work for their members.

They also supervised the admission of new apprentices to their craft and monitored their progress.

The Guildhall in the market place was built in 1356, was considerably improved by Bishop Tunstall in 1535, further rebuilt by Bishop Cosin in 1665 and altered again in 1752.

The wide range of crafts active in Durham between 1345 and 1667 included weavers, websters, cordwainers, barber surgeons, waxmakers, ropers, stringers, skinners, glovers, butchers, goldsmiths, pewterers, potters, painters and many more, not forgetting the less well-remembered lorimers, girdlers and listers.

The people of the city were still occasionally allowed onto the great space in front of the cathedral church so that the link between church and people was maintained.

One such event that all guild members were expected to attend was the annual procession on the Feast of Corpus Christi, which took place on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday.

A 16th Century record of one of these gatherings explains that: "On that day the Town Bailiff would stand upon the Toll Booth in the Market Place and summon all the various guilds of trades and professions to get out their banners and torches and go to the north door of the Cathedral where they would form a line, banners to the west and torches on the east side of the path as far as Windy Gap.

"In the church of St Nicholas there was a fine shrine which was carried in the procession. It was well gilded and had on its top a square container of Crystal in which the sacrament was kept.

"Four priests carried it up to Palace Green, preceded by a procession of people from all the churches in the town. " After it was blessed in the cathedral, the shrine was returned to the vestry in St Nicholas' church, where it was kept until the next year.

Also on that day, members of the various guilds performed dramas, probably similar in style and content to the York Mystery Plays, on Palace Green.

When Henry VIII sent his commissioners to Durham to close the monastery, one of them, a Dr Harvey, trod on the shrine and it fell to pieces.

The blessing of colliery banners in the cathedral at the annual Durham Miners' Gala could have been a folk legacy of the Corpus Christi procession.

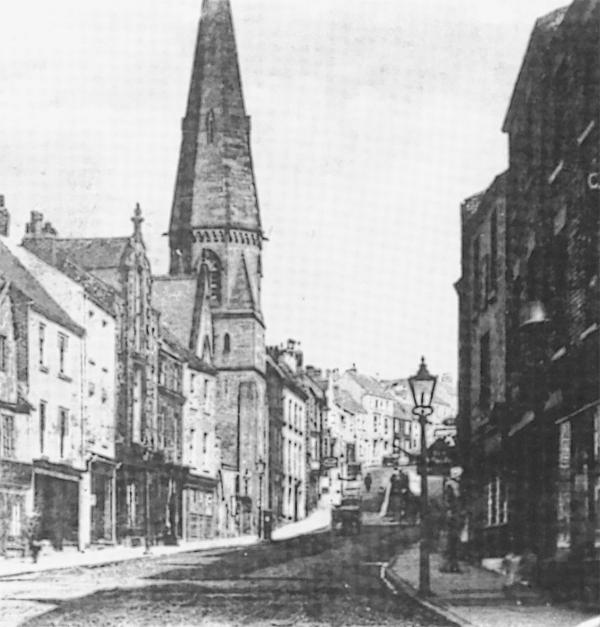

By the middle of the 19th Century, both the Guildhall and St Nicholas' church had seen better days.

Between 1857 and 1858, the church was almost completely rebuilt to a design by JF Pritchett, of Darlington.

It was the first in the city to have a spire and was described in the national press of the time as "the most beautiful example of church architecture in the north of England".

The Guildhall had been given a facelift eight years earlier with the addition at its rear of a town hall, designed by Philip Charles Hardwick as a smaller version of London's famous Westminster Hall.

VISITORS to the town hall today are always fascinated by a very small suit of clothes and other items that once belonged to one of the city's most famous residents.

Only 39in tall but perfectly proportioned and a respected member of Durham society, "Count" Joseph Boruwlaski had been born near Chaliez, in Poland, in 1739.

When his family fell on hard times, Joseph was adopted by the wealthy Countess Humieski, who took him on a tour of Europe when he was 15.

He was feted everywhere he went, mostly royal courts, and once sat on the knee of the Empress Maria Theresa.

She tried to give him a beautiful ring from her finger, but because it was far too large, she called over a six-year-old girl who removed one of her rings and gave it to her.

That child was Marie Antoinette, the future wife of King Louis XVI of France, who would be beheaded on the guillotine before the century was out.

Boruwlaski was more fortunate and lived until he was 97.

After many adventures on the continent, he eventually settled in Durham, where he made many kind and influential friends.

Buried inside the cathedral to the west of the great north door, his last resting place marked simply with the initials JB, he once wrote of himself: "Poland was my cradle, England is my nest.

Durham is my quiet place, Where my bones shall rest. " ANOTHER famous son of Durham is remembered on a plaque in the town hall.

Granville Sharp, born in the city in 1735, became one of the country's most determined fighters for the abolition of slavery and it was largely due to his constant campaigning that slavery was made illegal in Britain in 1772.

Sharp was also the cofounder and first chairman of the British and Foreign Bible Society.

The Market Place in Durham is still remembered bymany people for a remarkable innovation that appeared there in 1932 - the world-famous dometopped police box in which there sat a solitary policeman.

His job was to control the traffic that entered or passed through the Market Place via Silver Street, Saddler Street, Elvet and Claypath.

The great amount of congestion with which he had to deal is inconceivable to those who know the city's traffic system only as it is today, with the Claypath underpass along with the Milburngate and New Elvet bridges.

In those days, the policeman could see only the Claypath traffic and had to assess for himself from personal experience how much traffic was waiting to enter the space he controlled.

He operated the traffic light system himself.

In December 1957, a new police box was installed on the same site, but this had two television monitors connected to cameras on poles to help the duty policeman to make his decisions.

It was not until 1975 that the days of the Market Place police box came to an end.

Two impressive statues also keep watchful eyes on the comings and goings around the Market Place.

Mounted astride his great charger is Charles William Vane Stewart, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, 1st Earl Vane and Baron Stewart of Stewarts Court, portrayed in his Hussars uniform.

The statue, made of plaster coated with copper, an early example of electroplating, was executed by the Milanese sculptor Raffaelle Monti.

Despite having been a daring and brilliant soldier, Londonderry, who inherited his title in 1822, was very unpopular with the Durham coalminers, many of whom were his employees.

When Durham City Council discovered just how large the statue and its plinth were, they tried to have it sited on Palace Green rather than in its present position, but failed in their attempt and the unveiling took place on December 2, 1861. It was restored in 1952.

The other statue is older than that of the marquess and now stands in the Market Place for the second time.

Neptune, God of the sea, symbolised a plan to turn Durham into an inland sea port by altering the course of the River Wear. However, the plan never made it off the drawing board, and the statue is all that remains.

Originally placed there in 1729, a gift to the city from George Bowes MP, it stood at first on top of the public well heads before being repositioned in 1863 on top of the replacement wellhead.

Again, in 1902, it was placed on top of the next pump.

In 1923, however, it was moved to Wharton Park, where it was eventually badly damaged when struck by lightning.

Moved again in 1986, it was restored by Andrew Naylor of Telford and returned to Durham Market Place in 1991.

Durham has another market at the side of the Market Place.

The recently-renovated indoor market is a large treasure cave of shops protected from the elements by the building under which it nestles and, like the rest of the Market Place, is well worth exploring.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here