LAST year on Remembrance Sunday, the streets of Durham were filled with thousands of people watching the parades which pressed up on to Palace Green and into the cathedral for the traditional service where the DLI Chapel was a star attraction.

This year, there won’t be such crowds. There will be no public access to the cathedral on Sunday, although the service will be beamed live on the cathedral’s Facebook page from 10.30am, and so for the first time probably in 97 years, the DLI Chapel will not have the same numbers of people remembering their family members.

The chapel is dedicated to the regiment, the Durham Light Infantry, that bore the county’s name from 1758 until 1968.

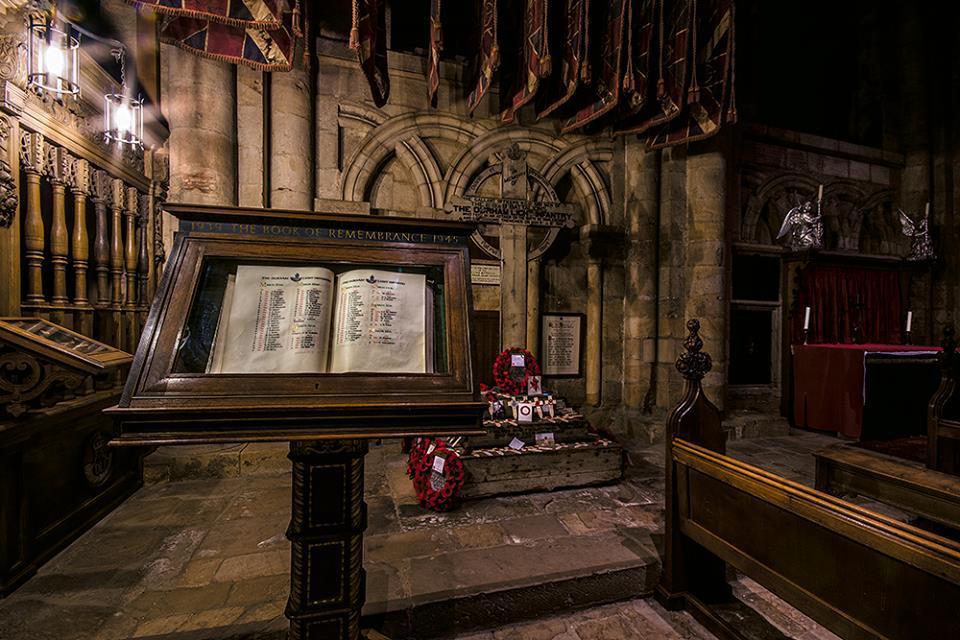

The chapel was created after the First World War, but it commemorates the soldiers who lost their lives as far back as the Peninsular War of 1811 to 1814 and the Crimean War of 1854 to 1858. The Remembrance Books, their pages turned daily, bear the names of 12,556 men who died in the First World War, and of 3,011 men who died in the second. Durhams who died as recently as Northern Ireland in 1973 are also commemorated.

The chapel was consecrated on October 20, 1923, in front of 400 soldiers and thousands of people, according to the Advertiser’s sister paper, The Northern Echo.

The Bishop of Durham, Hensley Henson, told them that the British soldier was essentially an influence for peace rather than war. “Indeed, the British soldier carries ever in his heart the love and hope of peace,” he said.

Also speaking that day was Lord Londonderry – a fascinating character who witnessed the slaughter of the Somme first hand, became an aviation minister in the 1920s defending the RAF but who gained a reputation as a friend of Hitler during the 1930s as he entertained the German ambassador at Wynyard Hall.

He spoke in praise of the Durhams, whose “ready response was second to none, and the numbers of battalions of Durham men, who fought in all parts of the far-flung British lines bore eloquent testimony to the spirit which actuated the miners, the agriculturists and the townsmen of Durham, and had justified their faith and confidence in the county”.

Perhaps pride of place in the DLI Chapel goes to the three wooden crosses which in 1917 were placed on the Butte de Warlencourt on the Somme in memory of the 273 Durhams killed there.

The Butte was an artificial mound which loomed over the flat battlefield and was held by the enemy.

On November 5, 1916, three battalions of the DLI tried to capture it: 6DLI from Bishop Auckland went down the middle, 8DLI on the right, and 9DLI on the left. The 9DLI were led by Lt-Col Roland Bradford, born in Witton Park whose family home was in Milbank Road, Darlington. A month earlier he’d won the Victoria Cross, and that day, he led his men into the maze of trenches dug deep into the Butte.

They held on for about 11 hours before they were driven back to where they had started, leaving many of their fallen comrades drowned in the mud.

The Butte was eventually captured on February 24, 1917, and Major Robert Mauchlen, an architect from Newcastle, designed three wooden crosses – one for each of the battalions involved – which were placed on the mound.

In 1926, the crosses were brought home to Durham. One was placed in St Andrew’s Church at Bishop Auckland, one at St Mary and St Cuthbert’s Church in Chester-le-Street while the largest went into the DLI Chapel.

In 2016, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the engagement, all three of the crosses were re-united in the chapel so that they stood arm to arm just as they had once stood on top of the Butte where so many Durhams had fallen in the hand-to-hand fighting.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here