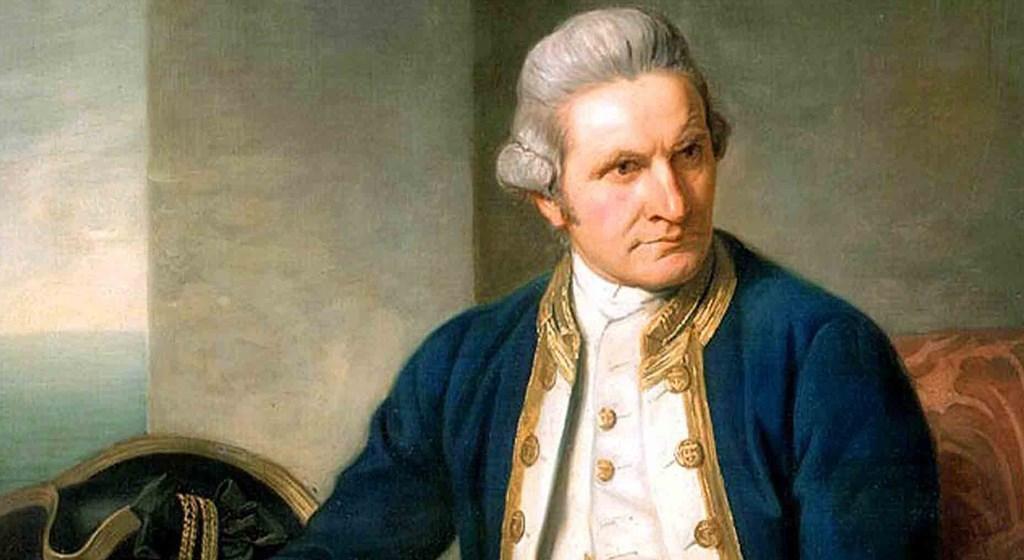

Harry Mead leaps in to protect the reputation of an explorer who was once regarded as the greatest ever Yorkshireman but whose 250th anniversary has raised heckles around the world

IT was Yorkshire’s homecoming of the century. Perhaps you were there – one among many thousands. You will have secured a smidgeon of space on Whitby’s cliffs, or its piers or harbour frontage. Scarcely a square inch was left vacant.

The unforgettable occasion, on May 9, 1997, was the arrival of the replica of Capt Cook’s ship, HM bark Endeavour. While the crowds cheered, and smoke from a cannon discharged by Endeavour drifted up towards the abbey, a large harbourside banner proclaimed: “229 years late.” That was the interval since the original Endeavour, built in Whitby in 1765, had set off, from Plymouth, on the first, and greatest, of Cook’s three epic Voyages of Discovery – explorations that changed the map of the world more than any others before or since.

But alas, Whitby’s rapturous welcome for the replica Endeavour is a far cry from her reception at places on the far side of the globe on a voyage commemorating the 250th anniversary of perhaps the outstanding achievement of her original journey – the circumnavigation of New Zealand, which established that its consists of two islands.

The Endeavour has been labelled “a death ship”. Cook himself has been branded “a barbarian”. Feelings have run so high that the replica Endeavour has steered clear of a number of places visited by the original – no doubt wisely, since it has even been suggested the replica should be set on fire.

Root of the trouble is the deaths of nine (or possibly ten, the figure is uncertain) Maoris shot by Cook or his crew. In Maori eyes not only Endeavour and Cook but Cook’s navigational and mapping achievements are irredeemably blighted by the violence.

Back home, schoolchildren in Capt Cook’s boyhood village, Great Ayton, have been preparing as usual for the annual celebration of Cook’s birthday. They were making model boats, to be sailed on the River Leven on Wednesday, three days after the actual birthday.

But, with a public statue of Cook in New Zealand recently removed to a museum, and graffiti having been daubed on ‘Cook’s Cottage’ in Melbourne, his parents’ home transported from Great Ayton, anti-colonial accusations against Cook are seriously beginning to cloud the reputation of a man who has been among the most admired figures in British history – incidentally voted the greatest Yorkshire person of all time in a Yorkshire Post poll.

Cook badly needs some words in his defence. The best that is said at the moment is that it is unfair to judge historic figures by the values of a later age. That simply reduces Cook to the ranks, among countless others. He is surely better than that.

The first of five instructions Cook gave to his crew was that they should “endeavour, by every fair means, to cultivate a friendship with the natives, and treat them with all imaginable humanity”. In a remarkable passage in his journals, Cook writes admiringly of the simple lifestyle of the indigenous Australians – the Aborigines. He thought them “far happier than we Europeans, being wholly unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary conveniences so much sought after in Europe. They are happy not knowing the use of them. The earth and the sea furnish them with all things necessary for life. They covet not magnificent houses, household stuff etc…”

But what of the Maori killings? Baldly stated, without context, they no doubt feed into the concept of an imperialist bent on conquest, with trifling regard for the indigenous people. But the truth is more complex.

Cook’s aim was always to establish goodwill. But his landings in New Zealand were against the background of an earlier voyage there by the Dutch explorer, Abel Tasman. Four of his crew were clubbed to death, which persuaded him to abandon his exploration.

Cook usually won the trust of the natives by presenting them with gifts or exchanging items. He records putting aside his musket and touching noses with a leading tribesman. But, in the worst of the violent incidents, his crew came under threat from a large number of Maoris. Shots over their heads didn’t deter them, and Cook recorded: “We were obliged to fire upon them in our own defence. Four were unhappily killed.”

In perhaps a reference to the Tasman sailors’ fate, he added: “I am aware most humane men who have not experienced things of this nature will censure me, but I was not to suffer myself or those with me to be knocked on the head.”

Another death occurred when, while Cook was on shore, a Maori trading at the Endeavour refused to give anything in exchange for some cloth he had accepted. He went on to shake his paddles at the ship, at which the officer in charge shot him. Cook wrote: “This did not meet with my approbation. I thought the punishment a little too severe for the crime, and we had now been long enough acquainted with these people to know how to chastise trivial faults like this without taking away their lives.”

Only “a little” too severe might be a black mark against Cook. But even soon after a death, the Maoris often would resume trading, some even voluntarily boarding Endeavour. One visiting Maori told Cook he had been “induced to come” by an account given by others of the “kindness” they had received, and “the wonders that were in the ship.”

It can’t be denied that Cook had the colonial mindset of his time. He didn’t question the right of Europeans to plant a flag and declare the place theirs. Telling how he named a New Zealand inlet Queen Catherine’s Sound, he declared: “I hoisted upon it the Union flag, at the same time taking possession of this and adjacent country in the name and for the use of His Majesty King George the Third.”

But it’s equally certain that if Cook hadn’t annexed New Zealand for a European nation some later explorer would have done so. Would there have been any less loss of life? Would any other explorer have been more determined, or even as determined, as Cook to avoid it? And would any other have gone virtually half way to meet the criticism now levelled at him by Ben Taylor, a leader of the Noongar Aboriginal people of Western Australia: “He put that flag up and all that flag has brought is misery, the loss of culture, the loss of our religion and everything – and all the massacres. That replica ship is the symbol of dispossession.”

Cook fully recognised the vulnerability of the indigenous peoples he encountered. “We debauch their morals,” he wrote. “We introduce among them wants and perhaps diseases which they never knew before and which serve only to destroy the happy tranquillity their forefathers enjoyed. If anyone denies the truth of this assertion let him tell me what the natives of the whole extent of America have gained by the commerce they have had with Europeans.”

Are those the words and sentiments of “a barbarian”, senseless to everything except the aggrandisement of his King and Country?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel