IT is sad when any dale village loses its only shop, but there may be more regret than usual over the next one to suffer this fate.

That is because the store at Westgate, which is to be shut in April, has given local folk excellent service for over 100 years.

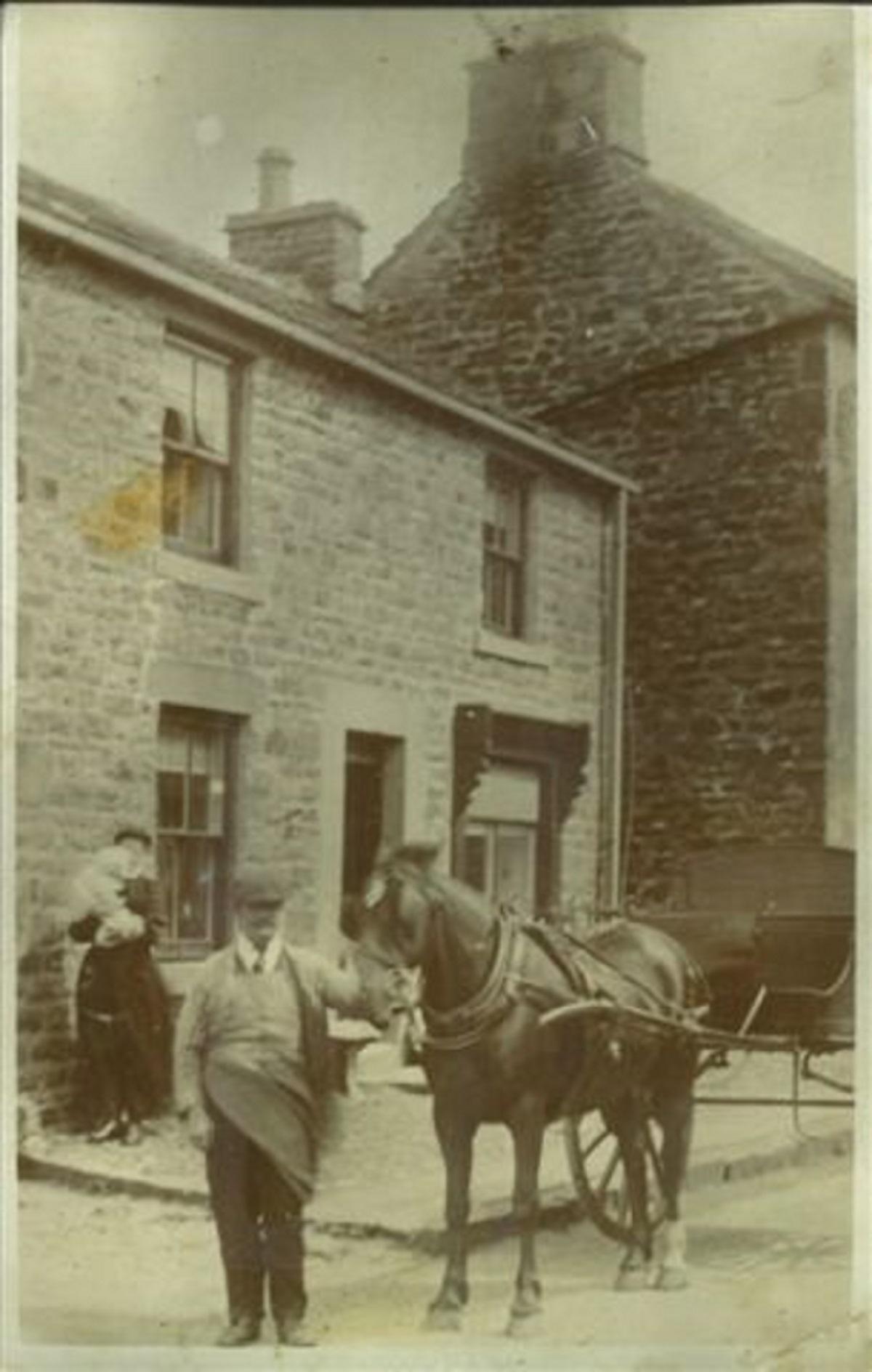

It was run in the 1800s by butcher James Elliott. Later it was taken over by another butcher, Harry Walton. As well as selling meat over the counter he toured the area, delivering from his horse and cart.

Then the premises became a Co-op outlet, as part of the Stanhope and Weardale Industrial and Provident Society. This body was set up in 1865 at a meeting in the waiting room of Stanhope railway station.

By 1895 it had 875 members and paid a dividend of just under three shillings in the pound.

The shop has been a co-op ever since, one of several dotted around the dale, though the controlling body changed to the Penrith Society and later ScotMid.

Now the Scottish bosses have decided trade is too slack in Westgate. So unless a buyer comes along, and that looks virtually impossible, the rugged village will be shopless.

There were plenty of them in Westgate 120 years ago, most selling food items. Three were listed in an 1894 directory as grocers run by Thomas Armstrong, Joseph Martindale and John Robinson.

Four others were described as grocers and drapers, a combination which seems unlikely today but was common then. They were operated by Edward Fairless, Mary Ann Moore, Elizabeth Vickers and Mary Myers with partner Ralph Dalkin.

The post office, run by Hannah Vickers, also had a grocery section. Mabel and Esther Grey sold only drapery at their establishment. William Lonsdale was a tea dealer. So there was plenty of choice for all customers.

Mark Teesdale, the miller at High Mill, probably also sold flour, and some of the many farms around the village were able to offer dairy produce.

There were also three public houses: Half Moon, where Mrs Burrow was licensee; Miners Arms, run by Joseph Parker; and Hare and Hounds, managed by George Moffatt, who also worked as a joiner.

Also busy in the village were Joseph Dalkin and his son, Joseph Junior, blacksmiths; George Hodgson, solicitor; and George Race, architect and builder.

The Board School, built in 1875, had places for 236 pupils in 1894. The number of shops was gradually whittled down. But Peter Nattrass, who loaned the old photographs shown here, recalled that even in the 1950s there were four general dealer shops, a bakery, a sweet shop and a post office, plus a shop on the village caravan site.

Now the post office is included in the shop about to close, and the hope is that a mobile service will replace it.

John Guyon, who heads a team that has investigated the possibility of villagers taking over the shop and running it, says it is out of the question. He also feels nobody will be silly enough to buy it in the hope of making a profit. Too many local folk go away to shop at supermarkets, and too many vans from Tesco and other firms deliver in Westgate.

But after getting expert advice he is still looking into the chances of setting up a small retail service to help those who need it. Two public meetings have been held and a third will be arranged before a decision is made.

MARY Gaines liked visiting the dales, and as she was well off she was able to give food and money to struggling families.

She admired the poems of Richard Watson, and when she heard he was even more impoverished than usual in later life she made special journeys to his home in Middleton to hand over groceries and cash.

After one visit she wrote of him: "He may be styled the Burns of the north. He paints for us a hundred beautiful pictures and there is a bouyant music in his verses."

He enjoyed poems she wrote, including one which started: "A poor man served by thee shall make thee rich/An old man helped by thee shall make thee strong."

But Mary also had a keen interest in palm reading, and it got her into trouble. She studied it seriously and claimed she read palms only to give pleasure But in 1893, two years after Watson died, she was charged with unlawfully using palmistry to deceive people.

It is possible that she read the hands of the poet and his wife Nancy when she visited them, as Watson was always interested in anything new to him.

The well-heeled old lady denied the charge in court at Darlington.

She had advertised in several papers, including the Northern Echo, saying people could call at her home in Cleveland Terrace to have their palms read for two shillings (10p).

The wives of a police sergeant and constable told of going there, having their hands studied and being told things that might happen in future.

The prosecution said this amounted to fortune telling, which was illegal. Her solicitor claimed she merely read palms to study character and indicate what this might involve, but it was a science, not fortune-telling.

She had given away a lot of money to help poor people, he added, and would never deceive anyone to earn a few shillings. But she was found guilty and fined 10 shillings. Watson could have written a memorable poem about the case if he'd still been around.

MIKE Stow doesn't know the names of the men on the coach seen here passing through Cotherstone in a picture from his collection.

It was from an era when the road surface was rough and there was still a thatched roof on the Red Lion Inn, shown on the left. He is also unaware of why the man on the right seems to be wearing a red coat and strange white hat.

But the picture brings to mind the story of Willie Stabler, who was a cobbler in Cotherstone in the 1840s. He was known to like a spot of fun when not mending boots and clogs.

One day he decided to play a prank on a wealthy man who was often driven through the village in a high quality coach, a conveyance much grander than the one in this illustration.

The rich fellow, who may have been Squire Hutchinson of Eggleston Hall, sat in swanky comfort in the well-cushioned interior, while his coachman sat in the open at the front, controlling a pair of splendid horses.

Willie, who had just bought an expensive new coat, stood at the Romaldkirk end of the village waiting for the gleaming coach to come over the bridge.

As it slowed to go round the bend he leapt onto the back. He stood there grinning broadly and waving to local folk who were standing around. But suddenly his coat tail got caught in one of the wheels. He struggled to get it free but it tightened round him and he was in danger of being pulled under.

He yelled for help. The rich man looked out, spotted him and shouted to the coachman to hand over his whip. He leaned out and started lashing Willie, who managed to wriggle free and jump clear, leaving his coat to be churned up.

A long poem about the incident was written by another village cobbler, John Hutchinson. It ended: His heart no doubt within him burned/That he in such a plight was turned/Without his coat to roam/To ride in chaise folks fondly talk/Those who have strength had better walk/Or be content at home.

The ode was passed round and had people chuckling at poor Willie for a long time.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here