When David Evans was ten in 1930, he was sent to live with his relatives for a few weeks while his mother gave birth to his brother, and he found himself transplanted into the Crisp family’s market gardens.

THE gardens stretched from Hurworth to Neasham along the banks of the Tees and over fields reaching towards Darlington.

They had greenhouses, strawberry patches, potato beds and orchards with the riverbank itself especially good for growing lettuces.

“I remember being with John Crisp in a greenhouse on the bank and he cut off a tomato and said ‘that’s for thee’ – because that’s the way he spoke,” says David, who is splendidly well at 91.

All of Crisps’ hothouses and gardens have now gone. Even some of their homes at the east end of Hurworth have been demolished. But, as Memories No 23 illustrated a fortnight ago, they and their horse-and-cart fruit-and-veg rounds are still remembered.

The Crisp story begins in the 1840s when George, the son of a shoemaker, moved from Malvern, Worcestershire, to be a gentleman’s servant in The Hall on Hurworth Green.

As he moved up in life, he rented the Strawberry Cottage smallholding, which still stands; the last house at the east of the village.

But in 1862, he contracted something nasty from the waters of the Tees – probably when rebuilding a restraining wall near a sewage outfall after a flood – and died, aged 38.

His wife, Jane, took over the gardens and brought up seven children until son John was ready. He proved himself a shrewd businessman, buying fields and properties and turning the smallholding into a large concern.

At this time, fate sent another family northwards into Hurworth: the Hutchinsons.

They were George and Anne plus their ten children, including twins Alice and Clara, who came from the Appleton Wiske area to labour.

John Crisp employed Alice as his domestic servant in Strawberry Cottage. Then he married her twin sister, Clara, and had 11 children who worked in the fields.

“I remember one meal when Aunt Clara come in with a great bowl of bacon and egg pie with crusts two inches thick,” says David, who is John’s godson. “It was too much for me, but the farm lads tucked in.”

The Crisps were renowned locally for their stalls on the markets of Darlington and Stockton.

To reach Stockton, the heavy carts of produce had to be hauled up Neasham bank – such a steep climb that the horses were exhausted when they reached the top.

“They untethered the horses and took them home and left the carts unattended overnight,” says David. The Crisps returned the next morning, with horses refreshed, and resumed the journey to Stockton.

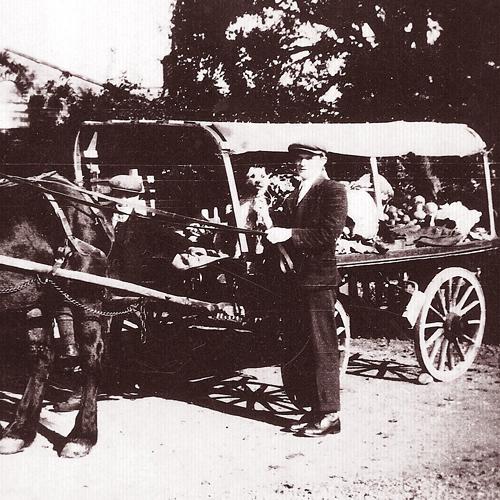

As Memories No 23 told a fortnight ago, the Crisps’ horsedrawn mobile shop is still well-remembered. The youngest of John Crisp’s sons, Albert and Arthur, were sent out on rounds.

“I remember sitting on the cart and I was in heaven, because while he was in the houses delivering, I could help myself to gooseberries,” says David, who lives in Norton, Stockton.

David’s grandmother was Alice Hutchinson, John’s domestic, and his mother was Grace. Grace attended Hurworth School, but with many uncles farming in the Tees Valley, she spent much of her childhood in Cleasby, and so he has a wonderful collection of old family photographs taken in both villages.

Grace trained at Darlington Teacher Training College and her first job was at Cleasby School.

Before the First World War, she fell ill and went to Saltburn to convalesce. There she met a soldier, David Evans, from the 7th (Cyclists) Battalion of the Welch Regiment.

Yes, with a name like David Evans, he was Welsh, and yes, with a name like 7th (Cyclists) Battalion, they were soldiers armed with pushbikes.

They were given the job of protecting the east Cleveland coast from invasion, although it is to be hoped that if the German army had landed at Redcar they were not stranded at the bottom of Saltburn bank.

KEN PUGH and Keith Aggett, both in Darlington, were Crisp cartboys in their youth.

Ten-year-old Ken was aboard with Albert Crisp in the Forties, pulled by Faithful the horse, who knew the route so well it was able to plod its own way round.

For delivering the produce to customers’ homes, Ken was paid a jar of pickled beetroot or cabbage and a couple of apples.

On a Sunday, Ken helped Albert in the greenhouses.

“We would be helping him potting on and then he would go a bit religious and we would have to stand there for an hour in the greenhouse while he did a Sunday service for us,” says Ken.

When ten-year-old Keith climbed aboard the Crisp cart in the early Fifties, he managed to negotiate a monetary wage for helping with deliveries along Neasham Road.

“The round could take a long time if he got chatting to people,” says Keith. “At the end, he’d tether the horse up in St John’s Crescent, put its nosebag on, gave me my 6d and I would walk down to Feethams for the football.”

MANY thanks to all who have been in touch recently.

More on the Keverstone Clog Factory and The Beatles’ favoured hotel shortly.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here