This week, Echo Memories goes in search of wobbly bridges, snow ploughs and a cheesy controversy

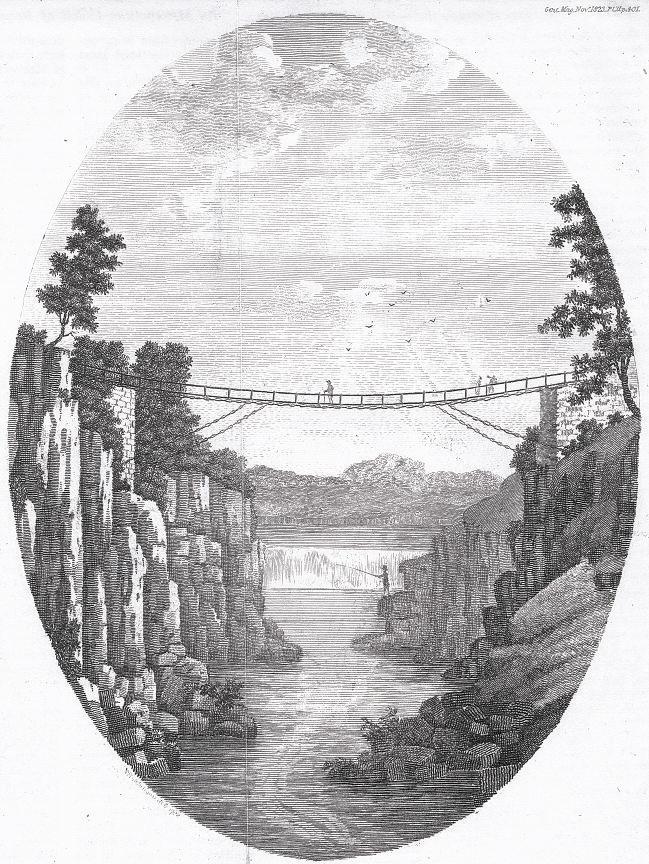

"TO persons accustomed to it, it is a very safe passage, but to strangers it is tremendous.

At every step, the chains and their superstructure yield and spring, and there is no safeguard for the passenger but a small hand rail, which if leaned against gives the bridge a swinging motion, whilst beneath you yawns a black and horrid chasm, 60ft in depth, where the torrent rushes with a mighty noise amongst broken rocks.” – William Hutchinson, 1776

PERHAPS the most exciting way to cross the roaring River Tees is by foot over the Wynch Bridge in upper Teesdale.

It hangs from a couple of wires which have been fired across a sheer-sided rocky channel.

It swings and sways with every step, and jolts and jumps disconcertingly beneath your feet.

The dangling planks which support your weight hang by a thread which you feel could snap at any step and plunge you to a cold and painful end in the churning waters below.

A couple of weeks ago, an article in the Echo told of the world’s first railway suspension bridge, which was built in 1820 to carry the Stockton and Darlington Railway over the Tees near Stockton. That historic bridge’s foundations have just been rediscovered.

About 60 looping miles upstream is another bridge first: Britain’s first suspension bridge of any kind.

It is the tremendous Wynch Bridge near Bowlees, to the west of Middleton-in- Teesdale.

It was built in 1741 so that leadminers living at Holwick, on the Yorkshire side of the river, could cross over the Low Force waterfall and reach Bowlees. Then they’d climb up the side of the dale to mines with nithering names like Coldberry. They’d be away for a week, carrying their supplies over their shoulders in their leather “wallets”, and staying in remote lodging houses near the pit entrance.

Their bridge was very rudimentary. It had just a single handrail to cling on to, and the chains holding it up were handmade. It was 60ft across and about 20ft above the rock-filled water, which was more than 8ft deep.

The miners had to go with a suspension bridge because of the steepness of the cliffs and the depth of the chasm.

The ancient Chinese are supposed to have been the first to build a suspension bridge out of bamboo long before the birth of Christ, but it was the development of strong, flexible iron chains that encouraged Western man to trust his life to such contraptions.

The first iron chain suspension bridge in Europe was built in 1734 by the army of the Palatinate of Saxony over the River Oder in Prussia, at a place then known as Glorywitz.

Six years later, the leadminers of Teesdale built Britain’s first effort.

Thirty years later, the Great Flood of 1771 washed it away.

They rebuilt, this time with two handrails.

Still, though, it was precarious. So precarious, in fact, that it scared Barnard Castle solicitor and historian William Hutchinson so much that, when he wrote of it in his 1776 book about Teesdale, he imagined the terrifying drop to the water to be three times as deep as it really was.

Hutchinson, whose initials still spin in a weathervane over his house in Galgate, Barnard Castle, was so concerned that he didn’t dare venture across. Instead, clinging to solid rock, he marvelled as a local went over “with the steadiness of a rope-dancer”.

The bridge, he said, “is planked in such a manner that the traveller experiences all the tremulous motion of the chain and sees himself suspended over a roaring gulf on an agitated, restless gangway, to which few strangers dare trust themselves”.

He was right. The second Wynch Bridge collapsed in 1802 under the weight of a party of nine men and two women. Three men were thrown into the Tees. Two splashed safely into the water, but a third by the name of Bainbridge was “dashed to pieces” on a rock.

About 1830, with the financial assistance of the Duke of Cleveland, of Raby Castle, near Staindrop, the bridge was rebuilt once more.

Suspension bridge mania was now sweeping the country, and so the Earl probably had engineers to advise him. He moved the anchors ten metres upstream – away from the cascades which form Low Force – and erected metal pillars from which to suspend the chains.

It is this bridge, a Grade II* Listed Building, which still carries people over the river.

As it is only the width of a field from a layby on the main road – the B6277 – it is easily accessible.

A sign advises that no more than two people at a time should be on it, and even then it shivers and shakes in an unsettling manner.

But as you cross, imagine those leadminers 270 years ago who constructed the first one. No details remain about how they did it (or why they called it the Wynch Bridge), so we have to imagine… Over a few beers in the Strathmore Arms in Holwick, they drank inspiration from this newfangled bridge that had been built in faraway Prussia.

Down to the river they went, threw their cables over the gorge, tied them tight, and then sent one brave chap across on his hands and knees, fixing the deck planks as he went, swaying wildly as the river roared through the gulf below.

■ Many thanks to Michael Rudd for information.

Michael is the author of The Discovery of Teesdale, below, published in 2007 by Phillimore, a richly illustrated book which tells how the wonders of the dale were discovered and described by 18th and 19th Century writers and artists.

THE Tees has a third historic suspension bridge at Whorlton.

Our 2003 article about it will be posted on the Memories blog this morning.

Some strange sights on the railways

ECHO Memories was last up Teesdale in October, chuntering on about the opening of the Tees Valley Railway in 1868.

Since then, Tom Hutchinson, the Bishop Auckland historian, has sent this wonderful picture of Middleton-in- Teesdale station.

We were also wondering about the carved keystone of the road bridge at Lunedale. It appears to be a stony face.

The best – in fact, the only – explanation of this curiosity comes from Malcolm Ellison, of the North Eastern Railway Association, who wonders if it is a “laughing-greeting”

face. Bridges on the Union Canal between Edinburgh and Falkirk have such faces: those facing east are laughing while those facing west are crying.

They act as a greeting to those in the boats beneath.

Another noteworthy rector

He was the Right Reverend Henry Montagu Villiers who, in February 1861, appointed his son-inlaw, the Reverend Edward Cheese, to the lucrative post of rector of Haughton.

At the time, church corruption was regarded with the sort of horror that today we reserve for MPs and their expenses, and this blatant example of nepotism received national ridicule. The stress killed the 48-year-old Bishop in August 1861.

The vacancy that Mr Cheese controversially filled was caused by the death of the Reverend Dr Bulkeley Bandinel. As readers of the Memories blog will know – and, amazingly, those readers include Mr Bandinel’s descendants – Mr Bandinel is so famous that he even has his own Wikipedia page.

Dr Bandinel was of Italian descent, born in Oxford in 1781 into a family of clergymen. After a brief spell as chaplain aboard HMS Victory, his godfather, who was head librarian at Oxford University, got him a job in the library.

In 1813, Bulkeley succeeded his godfather, and in the following 25 years acquired 160,000 books from around the world, which helped make the Bodleian one of the great libraries – he was particularly fond of “incunables”, which are books printed before 1500.

In 1822, he was appointed vicar of Haughton-le- Skerne, a post that through a quirk of history enjoyed an extremely large salary.

He held the post until his death in February 1861, although he only visited the village a handful of times.

The biographies – he is also famous enough to have an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography – paint a mixed picture of him. He was very polite, even gracious, to those visitors he considered his superior in learning, book collecting and wealth.

But to those he considered inferior – daily borrowers, students and staff – he was rude to the point of naval vulgarity.

Dr Bandinel’s younger brother, James, also has entries in high places, as he was the Superintendent of the Slave Trade at the Foreign Office from 1824 to 1845, and so played an important role in the trade’s abolition in 1833.

For Haughton to have had another rector as famous as Mr Cheese is quite a coup for the village.

In a future week, we hope to tell of a third rector who should be equally as well remembered.

Battling bad weather on the tracks

THE recent weather has reminded us that we have some snowplough follow-ups from the article in November.

John Askwith, the archivist of the Weardale railway, sent some pictures taken by the late John Mallon showing North Eastern Railway (NER) snowploughs waiting for snow at Fieldon Bridge, Bishop Auckland, above.

Snowploughs always worked in pairs: one at the front of the engine, and the other at the rear, so the engine could get both in and out of drifts.

When being shunted in yards, snow ploughs were always chained pointy-bit to pointy-bit, as the picture shows.

Not every organisation was as sophisticated as the NER. Dennis Mawson emailed pictures he took in 1981 at Fishburn Coke Works of a homemade National Coal Board snow plough.

“A blade of sorts has been attached to both ends of the chassis of an old hopper wagon which appears to have been ballasted with any old rubble that could be found,”

he says.

“When photographed, it appears not to have been used for some time.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here