In appealing for information about a curious riverside stretch of south Durham, Tom Hutchinson and Chris Lloyd stumble across tales of floods, lunatics, boxers and a dumpling-eating sheep's head

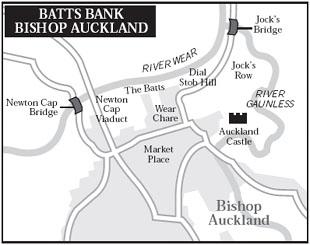

BISHOP AUCKLAND tumbles down Batts Bank towards the River Wear. The Wear Chare, a narrow snicket off the Market Place, runs down to Dial Stob Hill and Jock's Row on the waterfront where, in decades past, nearly 500 people lived.

The area is first mentioned in 1373, when the Bishop of Durham gives a hermit called William Sheplady "a piece of ground near the Wear, at the side of the highway leading from Aukland to Bychestre and Newtoncapp, eighty feet in length and forty in breadth, upon which to build a hermitage, to hold for life. Rent, a penny".

After the hermit, came the hordes. By the end of the 17th Century, a long line of low cottages had been built on the waterfront. It was called Jock's Row and was inhabited by members of "a numerous tribe", supposedly of gipsy extraction, who traded in mugs, brooms and similar household articles.

During the 18th Century, the settlement stretched from the foot of Wear Chare up to Jock's Bridge, where the Gaunless joins the Wear. But, practically all were swept away by the great flood of November 16 and 17, 1771.

The flood caused the Wear to dramatically alter its path, sweeping southwards so that it ran extremely close to the houses that remained in Wear Chare.

The children who lived in the houses now had a fatal plaything outside their front doors.

The Auckland Chronicle carried a report on Friday, August 28, 1891, which was headlined: "Sad Fatality near Bishop Auckland. A Child Drowned in the Wear".

The victim was six-year-old Robert Williams, of Jock's Row, whose father, Thomas, was a joiner at the Railway Forge.

"The little fellow got into the Wear at Dial Stob Hill, between six and seven o'clock in the evening, " said the paper. "The river was very much flooded owing to the recent rains, and the water at this point was three or four feet deep.

The force of the current carried the lad a hundred yards down the stream before he was stopped by a wire across the river."

The body was "recovered after half an hour's immersion by James Sullivan, the man who a year ago had the melancholy duty of taking out the dead body of a child drowned at the very same place". Mr Sullivan lived eight doors down from the victim's family in Jock's Row.

In the late Thirties, the river was diverted back to its 1771 route when huge deposits of colliery waste were deposited on the south bank. Even today, regular works by Northumbrian Water are a feature of the south side of the river from the viaduct at Newton Cap to the banks below the Roman fort at Binchester.

The Batts were the low-lying pastures beside the river.

Because of their open nature, they were ideal for large numbers of people, such as striking miners, to congregate.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Batts were used as a parade ground, and it was common for people living on the Bank to witness soldiers being flogged.

THESE were very different days, as this story from the late 1830s illustrates.

Dan Pickering was a waggoner who worked for George Maw, the tanner of Wear Cottage behind Wear Chare.

Dan lived with his mother in a house on the west side of Wear Chare.

One Sunday morning, she left him to keep the pot boiling on the fire while she went to chapel. In the pot was a sheep's head and a dumpling.

When the water began to boil, the sheep's head and dumpling began to dance and chase each other around the pot.

This so alarmed Dan that he ran away to St Anne's Chapel, stole quietly up the chapel stairs and waved at his mother.

She replied by waving dismissively in the opposite direction.

After several attempts to communicate in this way, Tom gave up and said in a loud whisper that could be heard by all: "Ye needn't sit nod-nodin there, for the sheep's hed is eating all the dumpling."

The people who lived in Batts Bank were humble folk. The 1851 census gives them agricultural occupations, such as tanner and currier, cordwainer, linen merchant, miller, handloom weaver and gamekeeper.

Some of these agricultural workers may have been employed by the Bishop of Durham at Auckland Castle.

But there were also new occupations, such as coal miner, brickmaker, policeman (William Brown, superintendent of police lived in Wear Chare). In all, the 1851 census counted 130 inhabitants (80 per cent of them born in County Durham) in 48 households.

The area had changed rapidly by 1871. The agricultural workers had largely gone, replaced by an industrial breed.

There were plenty of coalminers, plus a blacksmith, bricklayer, cartman, coke drawer, engine fireman and instrument maker among the 491 inhabitants.

Forty-eight of them had been born in Ireland, who tended to live in the poorer houses and lodging houses of this humble area.

By 1901, the vast majority of men of working age were miners - or coal hewers as the census enumerator called them.

In one terrace, Batts Row, 19 out of 20 householders were miners.

There were now 440 people living in Batts Bank, although the Irish influence was being watered down: only five per cent of the inhabitants gave their birth place as the Emerald Isle.

Most of the houses in Batts Bank were condemned as unfit for human habitation at the end of the Fifties, and were demolished. Today, only eight brick houses from the early 1900s remain.

PROBABLY the most famous resident of the Batts - or, more correctly, infamous - was Jonathan Martin.

He was a lunatic who, born in 1782, had taken against Church of England clergy.

He was wellknown in the district because he liked to hide in pulpits before a Sunday morning service started. He would jump up when the service was under way and start ranting about the perniciousness of the priests.

He, too, worked in George Maw's tannery, and lived nearby. He took his exercise on the Batts, dressed eccentrically in a suit made, including cap and shoes, out of a calf's skin with the hairy side turned outwards.

Seeing such a hirsute jogger pounding the pastures was, according to Victorian historian Matthew Richley, "greatly to the terror of the rising generation of the town".

Martin tried his church trick once at St Anne's Church, jumping up from his pew and ranting.

The constable, Bill Ramshaw, was ready for him and, with the help of church officials, ejected him.

He went out into the Market Place, climbed onto a balcony above a shop in Fore Bondgate and, when the congregation came out, launched into his sermon entitled, "If the blind lead the blind they shall surely both fall into a ditch".

A large crowd gathered to hear his tirade, so the authorities pulled him down and locked him up in a lunatic asylum in West Auckland. He escaped a couple of times and went to live in Darlington, where the authorities thought him no longer dangerous.

How wrong they were. As Echo Memories told in 2005, on February 1, 1829, Martin hid in York Minster after evensong and set the place alight.

It was a blaze as tremendous and destructive as the one in 1984.

The life of Jonathan Martin is the subject of this week's podcast, which can be listened to, or downloaded from, The Northern Echo's website.

PROPERLY, the most famous resident of the Batts is boxer Jack Hayes from the Twenties and Thirties.

Most boxing biographers say that he was born in Hartlepool, where he fought most of his fights. The truth is, though, that Thomas Hay was born in 1902, at 4 Dial Stob Hill. He was the second son of Robert Hay, a labourer at a local pit, who also had six daughters.

When Tom - known as Tot - married Olive Hughes in 1925, at St Anne's Church, in Bishop Auckland, he was a miner still living down Batts Bank.

But he was also boxing under the punchy name of Jack Hayes. Most of his fights were in Hartlepool - he had 20 bouts at Duggie Morton's Pavilion, in Lynn Street. His opponents included "Thunderbolt" Smith, "Gunner" Ainsley, "Lanky" Allen, "Battling" Dunn and "Battling" Joojoo, from Ghana.

One of his most celebrated fights was on September 2, 1931, when he fought Pat Hopkins in Glasgow. After ten hard-fought rounds, Tot lost on points, but he was carried shoulder-high from the ring and cheered by the Scottish crowd.

In those days, the vast majority of boxers had other jobs. Tot was a steeplejack then a docker in Hartlepool, until he retired in 1967.

He died in the early Eighties while living at Hart Station.

No one really knows why he has never been acknowledged as an Auckland lad, from a family who lived in Dial Stob Hill from the late 1880s until the mid-Thirties.

And no one, outside of that family, knew that Tot lost his left eye at the age of eight in a children's game of bows and arrows down Batts Bank.

With thanks to Tot's nephew, Walter Young.

TOM HUTCHINSON, author of many historical books about the Wear Valley, hopes to publish a book this autumn, provisionally called Down the Batts Bank. Tom is appealing for photographs, information and stories about the residents from any era up to, and including, the Fifties. Contact Tom on 0191-4104383 if you have anything which could be of interest.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel