"WORK on the controversial Cow Green Reservoir, 1,600ft above sea level in Upper Teesdale, was begun yesterday with a bang and a puff of smoke,” reported The Northern Echo 50 years ago this week.

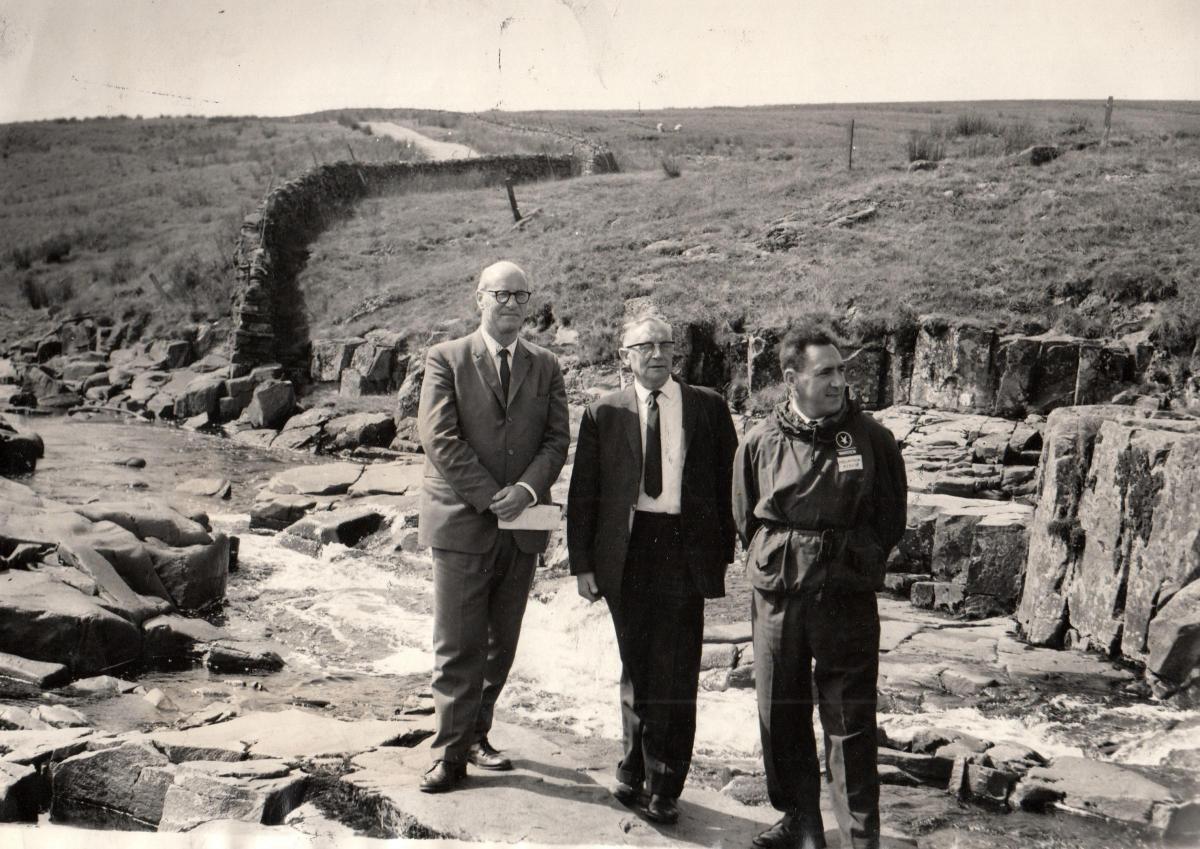

“Instead of the traditional turf cutting ceremony, the chairman of the Tees Valley and Cleveland Water Board, Alderman Sir Charles Allison, pressed the plunger of a hand detonator and blasted a crater on the site of the 1,900ft dam, which will hold back 9,000m gallons of water.”

Cow Green was the last, the largest, and the most controversial of the six dams built in upper Teesdale over the course of a century to satisfy the thirsts of Teesside’s growing industry. It holds nearly 41Mm3, more than twice that of the next largest in Teesdale, Balderhead, but only a drop in the ocean compared to Kielder, which opened on the North Tyne in 1982. Kielder contains 200Mm3, more than twice the combined capacity of the Teesdale reservoirs.

(Mm3 means cubic megametre and it seems to be the preferred measurement for reservoirs. One cubic megametric equals a little more than two gallons. Therefore, Cow Green’s 40.9Mm3 equals about 9,000 million gallons. If you are still struggling to comprehend, there are eight pints in a gallon, so Cow Green contains 72,000 million gallons, which is quite a lot.)

The first wave of reservoir building in Teesdale had been first mooted in the early 1870s, but it wasn’t until the 1890s that the first spades were put in the ground.

Similarly, the second wave was first been mooted before the Second World War, but it wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that the dams were built.

This second wave was presided over by Sir Charles, who on that day 50 years ago was said by the Echo to be in “challenging mood”. As he plunged the plunger, he said that people needed to understand that “we have not built it (Cow Green) for any other reason than to assist industry with its increasing needs for production”.

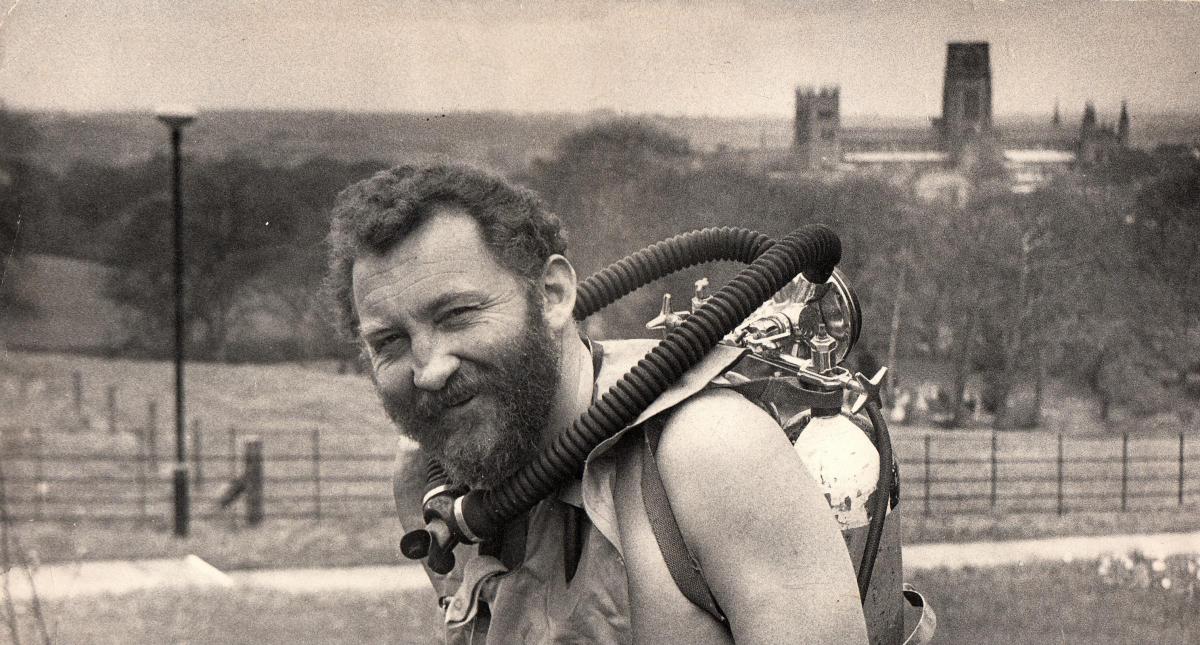

This was a nod to the controversy that surrounded Cow Green. Opposition to the reservoir had first surfaced in a letter published in The Times in February 1957, signed by 15 leading botanists, who feared it would damage the rare and precious environment of upper Teesdale. For example, one-tenth of the habitat of the extremely rare Teesdale violet was to be submerged, and one of the leading voices against the development was a lecturer in botany at Durham University, David Bellamy.

But after nearly a decade of battling, the battle was lost and so on October 12, 1967, Sir Charles got to blow up his bit of peat. For the water board’s guests, there was a rather chilly opportunity to inspect the site before all 100 of them went for a celebratory lunch at Scotch Corner. At the hotel, Sir Charles obviously thawed out because he certainly warmed to his theme.

He was infuriated that the green lobby had delayed the construction of his reservoir at a time when ICI alone was drinking 35m gallons a day and each man employed in Teesside’s chemical industries needed 1,250 gallons a day just to keep him in a job.

“I have from time to time expressed very strong views on the basis of the opposition’s case and I am bound to repeat that in my view, nowadays, we, as a nation, seemed to be so obsessed in preserving the past that we had become blinded to the need for future prosperity,” he said.

He was particularly scornful of one unnamed MP who had on several occasions used Parliamentary procedures to hole beneath the waterline the water board’s attempts to get permission for the reservoir.

Sir Charles concluded: “Does not this kind of happening which is blatantly another example of authority without responsibility, make one wonder how as a nation we will ever pull our socks up and be prosperous again?”

Sir Charles’ detonation allowed preliminary work to begin ready for the 300 workmen to start on the site in the spring when the weather improved. Their job took more than two years to complete, and the last of Teesdale’s reservoirs was officially opened in July 22, 1971.

ONE of the most intriguing aspects of Teesdale’s reservoirs is to think what may lie drowned beneath their cubic megametres of water.

The two Lunedale reservoirs submerged about 15 farms and houses between them, and at the very bottom of Grassholme is an old packhorse bridge which re-emerges in times of driest drought. It once had a mill, powered by the River Lune, beside it.

In 1984, there was so little water about that Cow Green itself sunk so low that a hitherto unknown Bronze Age farmstead was uncovered. Archaeologists had time to examine it before the waters rose once more.

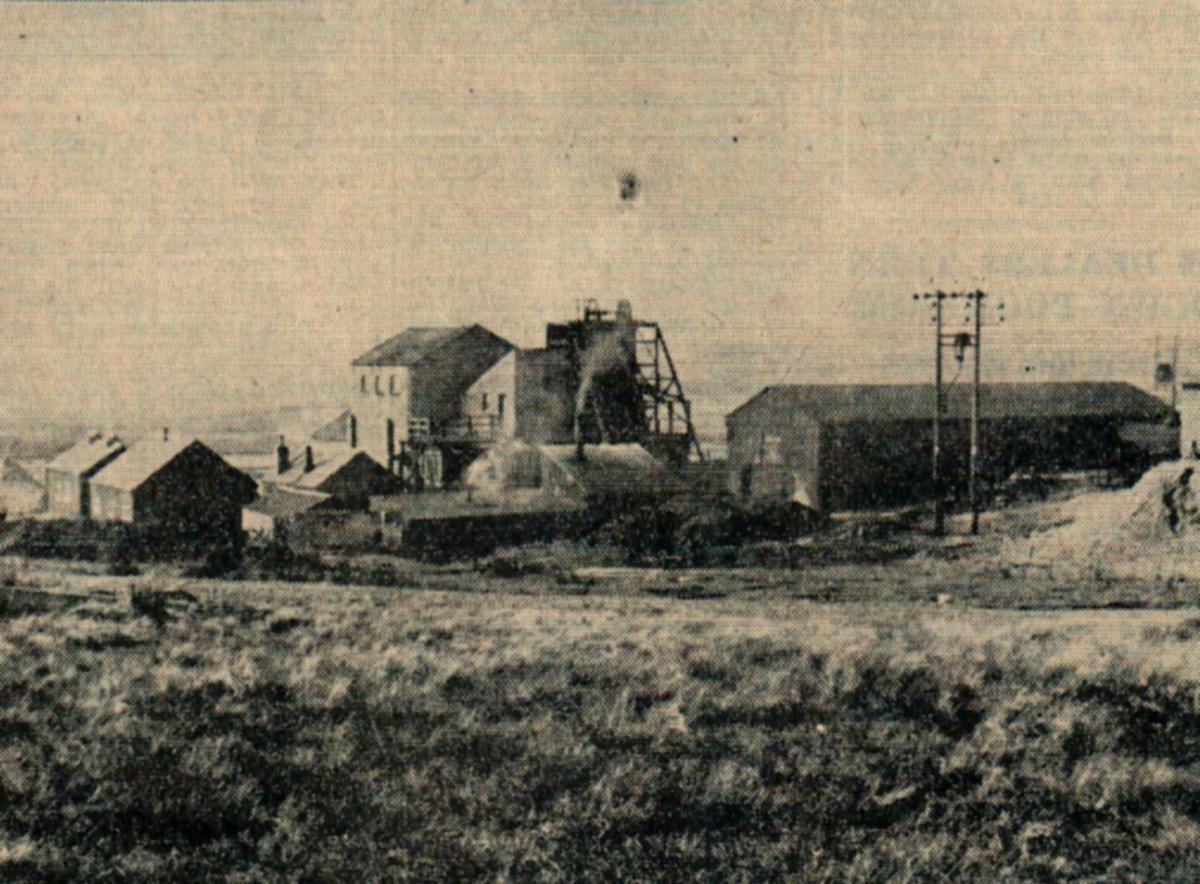

THE creation of Cow Green Reservoir overwhelmed the hope that Cow Green Mine could ever reopen.

For 200 years the mine, which was on the eastern shore of the reservoir, had been seeking out lead ore. In its later years, it went digging for barium sulphate, known as “barytes” which the Teesdale miners pronounced “brightus”.

“The commercial uses of barytes are many,” said The Northern Echo in 1954, “but it is predominantly used in making pigments for paints, as a filler in paper, linoleum, rubber and plastic manufactures and as a thickener in oil well drilling muds.”

Ironically, earlier generations of leadminers had thrown away barytes because they thought it was worthless.

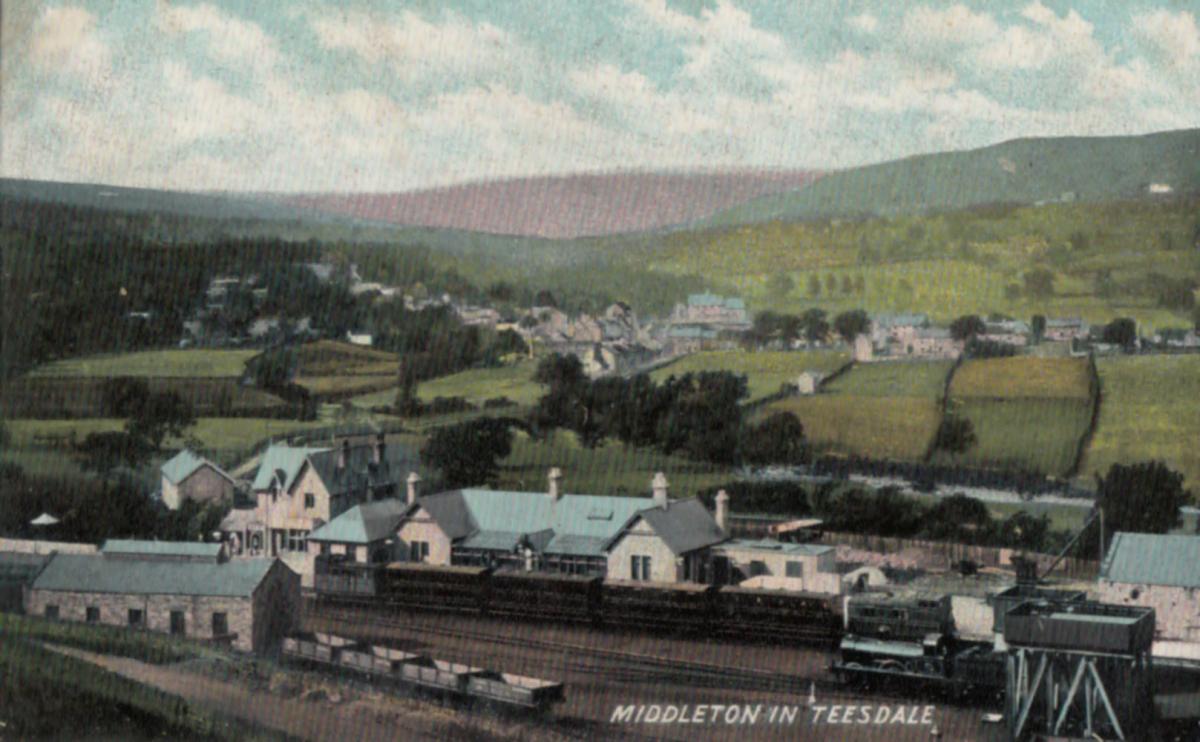

Since the 1880s, Cow Green Mine had been the principal employer in the upper dale, giving jobs to more than 130 men who were paid a total of £1,000-a-week – a huge sum for the local economy – as they brought 500 tons of barytes a week to the surface. It was then driven ten miles to the railhead at Middleton-in-Teesdale for onward transmission.

It was these distances that did for Cow Green. The weather up there was so bleak that the barytes were often snowed in for days on end, and the cost of transportation was very high compared to cheap foreign competition. The mine closed in May 1954.

“The shaft and mile-long levels are sealed off and most of the gear is going to Heights Pasture mine at Eastgate, in Weardale, while the headgear is going to Cumnock, in Ayrshire,” reported The Northern Echo. It also said that a few leadminers had found work at the Coldberry leadmine, near Middleton-in-Teesdale, while the rest had returned to farming.

“To Teesdale generally, and to hundreds of visitors who passed that way to cauldron Snout, Cow Green was ‘our mine’,” said the Echo in 1954. “Mines have a habit of coming to life again, but for the time being, Cow Green is just part of the fellside that once was a prosperous mine.”

When work started on the Cow Green dam 50 years ago, all hope that the mine would ever come back to life was extinguished.

CAULDRON SNOUT is just below Cow Green Reservoir. At 200 yards, or 180 metres, long, it is said to be England’s longest waterfall, although really it is a cascade or a cataract – it is a watery stairway as the River Tees descends down the dolerite steps of the Whin Sill rock formation.

Whatever Cauldron Snout’s geological claim to fame, it definitely possesses the best name of any waterfall in England. The best explanation for the name that we can find is that “cauldron” comes because the water is bubbling so much as it comes spurting down the stairway that it looks like it is boiling in a cauldron.

“Snout” could be because the water channel is long and thin in the shape of an animal’s snout, or, more likely, it could have started off as a “spout”.

Whatever Cauldron Snout’s derivation, it must be the only haunted waterfall in the country.

For sitting on the rocks beside the torrent on that isolated fellside, the Singing Lady is often spotted. It is said that she was a Victorian farmgirl who was so distraught when her Cow Green leadminer terminated their relationship that she threw herself into the boiling waters of Cauldron Snout. Now she haunts the place, singing out a spooky lament to her lost love.

A QUESTION OF SIZE

1894 Hury (Balder): 3.9Mm3

1896 Blackton (Balder): 2.1Mm3

1915 Grassholme (Lune): 6.1Mm3

1960 Selset (Lune): 15.3Mm3

1965: Balderhead (Balder): 19.7Mm3

1971: Cow Green (Tees): 40.9Mm3

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here