MARY SLAUGHTER was so concerned by the Zeppelin attacks on her home on Tyneside during the First World War that she left her husband and moved for safety to the quieter seaside town of Seaham, to stay with relatives.

At about 10.20pm on July 11, 1916 – exactly 100 years ago on Monday – Mary, 35, and her cousin Jennie Brown were walking home through the yard of Seaham Colliery after a pleasant night out in Dawdon when, more than a mile away, German submarine U-39 rose up out of the North Sea.

It fired 39 shells high into the air so that they flew over the seafront houses of Seaham Harbour – the U-boat commander, Konteradmiral Werner “Fips” Fürbringer, was apparently aware of the hostility caused by civilian deaths.

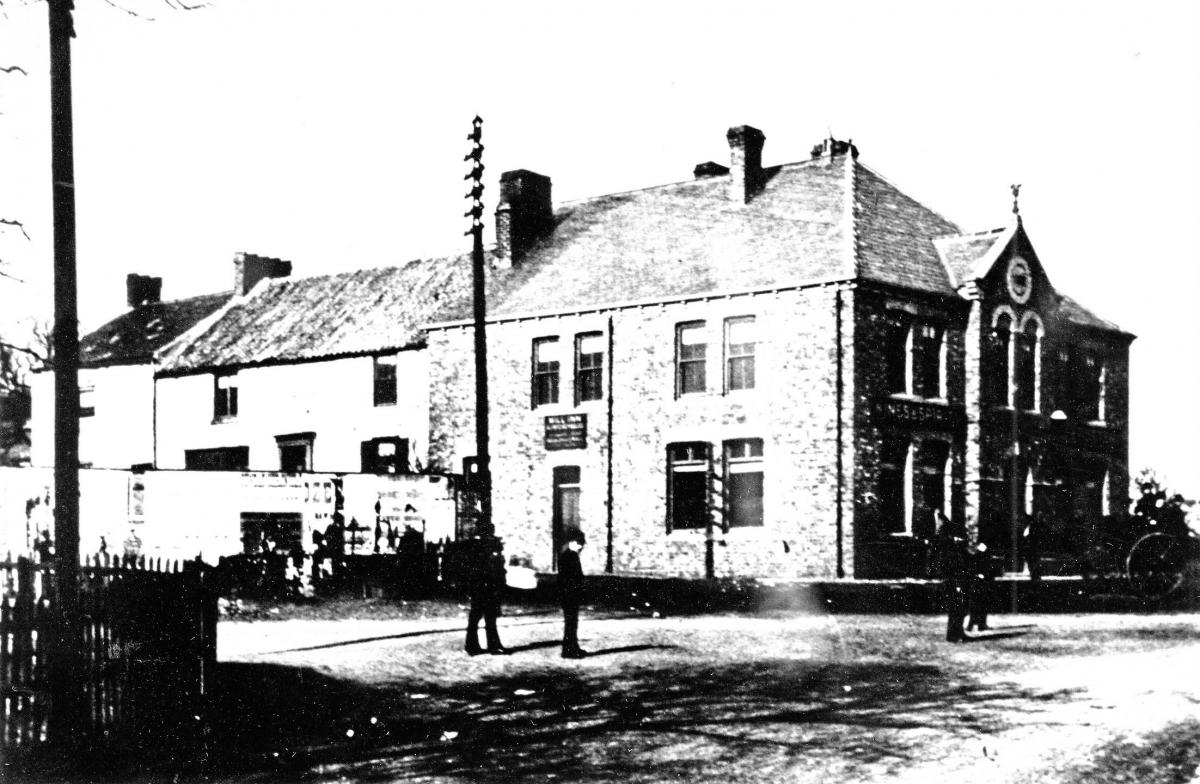

Most of the shells, therefore, fell harmlessly in the fields behind Seaham, but a couple slammed into the settlement of New Seaham which surrounded Seaham Colliery.

Miner Carl Mortinson and his family in 14, Doctor Street, had a lucky escape. A shell demolished their back yard wall, crashed into the house, flew across the kitchen, missing Mrs Mortinson, and landed at the front door. The rest of the family upstairs in bed were safe – but must have been shaken.

Mrs Slaughter was not so fortunate. As she and Jennie were “passing through Seaham Colliery yard, they heard a noise like an explosion, and saw a bright flash in the distance,” reported The Northern Echo on July 13, 1916.

“In turning, witness (Jennie) stumbled and fell down, and when she got up again she saw Mrs Slaughter lying on the ground, apparently injured.”

Mary had been hit in the arm, foot and head. She died a few hours later in Sunderland Infirmary, and the inquest into her death was held almost immediately.

It heard that the U-boat, which was not flying a flag, had been about 400 yards off Seaham Harbour when it opened fire – close enough for people on the shore to see the men on its deck operating the gun.

It also heard that a fragment of the shell that killed Mrs Slaughter was found to have “Krupp” on it – the famous company that manufactured much of Germany’s artillery during the war.

The Echo said: “The coroner, in summing up, said the jury would have no difficulty in coming to the conclusion that death was due to the explosion of a shell fired by a German submarine. They need not enter into any other question, nor did he think they should make any comment on the extraordinary mode of warfare.

“He thought, in view of everything, they could safely leave vessels of the class of the German submarine to his Majesty’s Navy.”

Mary was buried on July 15 in an unmarked grave in Hebburn Cemetery with her husband John, a blacksmith, in attendance. “The townspeople displayed their sympathy with the bereaved family by attending in large numbers,” said the Echo.

In 1933, Fips, the U-boat captain, published a book entitled Alarm! Tauchen!! U-Boot in Kampf und Sturm about his daring deeds during the First World War – he was a Red Baron of the seas, having sunk 101 British ships.

In it, he revealed that his brother had been killed on the Western Front six weeks before he shelled Seaham, and he suggested that his target was an ironworks on the County Durham coast. However, Seaham Colliery, which closed in 1988, would have been a worthwhile target for the Germans as it employed more than 3,000 men during the war and produced about 6,000 tons of coal a day.

In 1999, Alarm! Tauchen!! was translated into English and published as Fips: Legendary U-boat Commander. It revealed that Fips’ foreword had begun: “I dedicate this book to two innocent victims of the Great War: to the dearly beloved Fürbringer who, as legendary uboat commander a private soldier in the German Army, fell at Verdun on May 31, 1916, and to Mrs Mary Slaughter of Hebburn, a young lady visitor to the town of Seaham, who while taking a country walk in the company of a female relative on the evening of July 12, 1916, was hit by a shell fired by the German submarine UB-39 and succumbed to her terrible injuries at Sunderland Hospital the following morning, the only casualty of the incident.”

MARY’S hunch about the coast being safer than the city was not correct, as the bombardment of Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby on December 16, 1914, had shown – 137 people died and nearly 600 were injured.

Only two-and-a-half-months before Seaham was shelled, Yarmouth and Lowestoft in East Anglia had come under attack, and 25 people died.

Fishermen were particularly vulnerable. On July 14, 1916, the Echo reported how the previous day the crews of Scarborough steam trawlers Dalhousie and Florence had landed at Whitby in lifeboats.

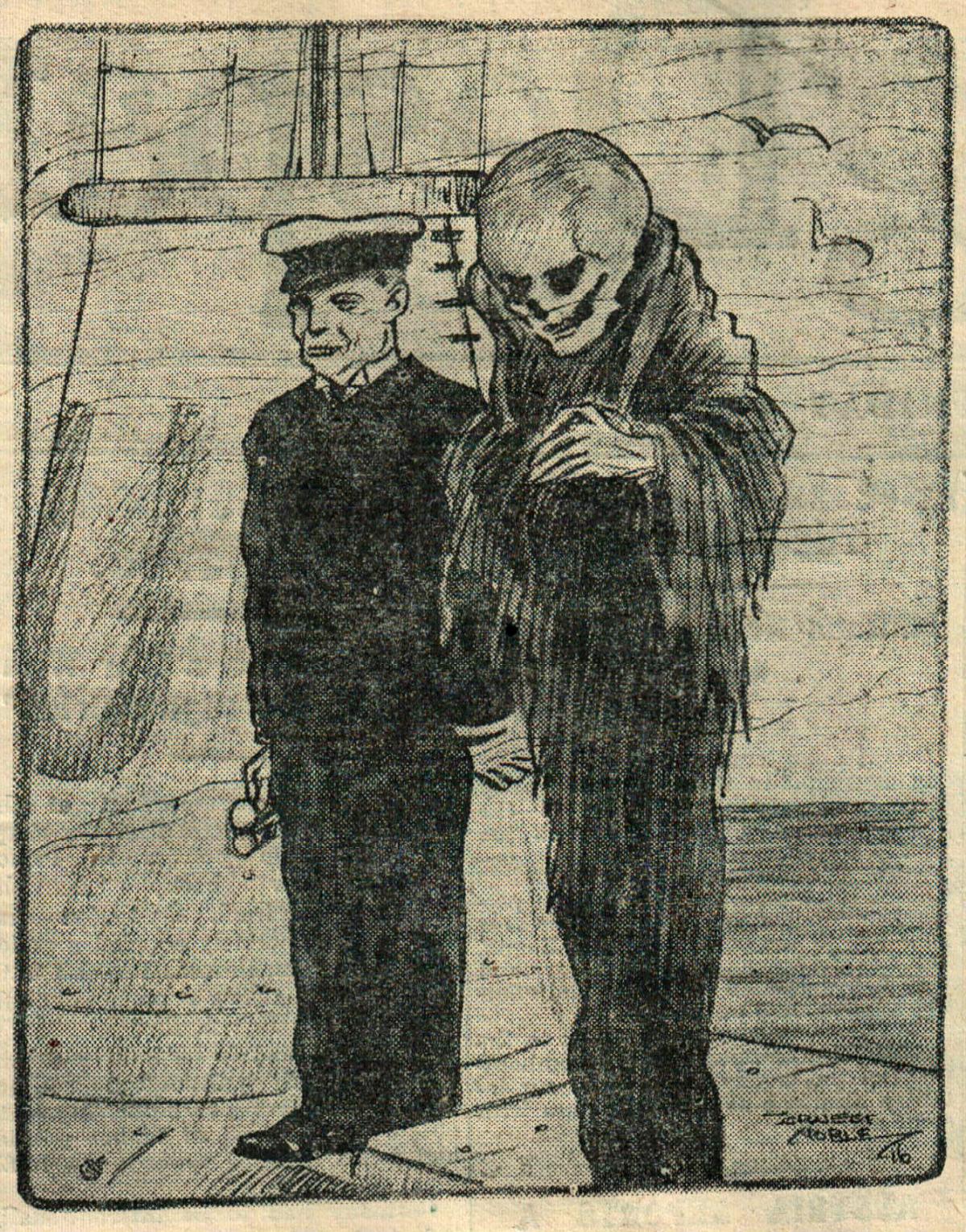

It explained how they had been captured: “The submarine commander approached the trawler and ordered the crew aboard his boat, after which the trawler was stripped of stores, a bomb subsequently play on board, and the vessel sunk.”

As these incidents happened about ten miles out, the U-boat commander put the fishermen into their own lifeboats and pushed them back to the coast.

That same day, said the Echo, the small trawlers from Staithes, Mary Ann and Success, had suffered identical fates.

THERE has been a surprising amount of interest in the old bullets dug out of a bank in Neasham where, during both world wars, there had been a rifle range – the bank was behind the targets (Memories 285).

In Memories 286, we concluded that the slender bullets were .303 from a rifle and the snub one was a .45 from a pistol. They could date from either war.

Now J Pattison writes from Middleton St George with even more information.

“The giveaway to the slender bullets is the dent on the side of the one on the right,” he says. “This makes it a copper jacket for an armour-piercing .303 bullet produced during the First World War.

“They were issued to marksmen to shoot at the engines of low flying aircraft, such as the AEG J.1, which could strafe infantry marching or mustering for an attack.”

The armour-piercing .303 bullet was introduced in 1915, and the AEG J.1 was an armour-plated German biplane introduced in 1917.

Mr Pattison continues: “The snub bullet is a phosphorus incendiary 20mm cannon round for a Polston or Oerlikon gun, which were used in both wars.

“During the Second World War, there was a 20mm cannon in our local sand quarry which the Home Guard and the Army used for training.”

IN Memories 286 while discussing these bullets, we mentioned Pat Surtees’ grandmother’s first husband who died near Ypres in 1917. We should have said that his name was Harry Heaton. Sorry.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here