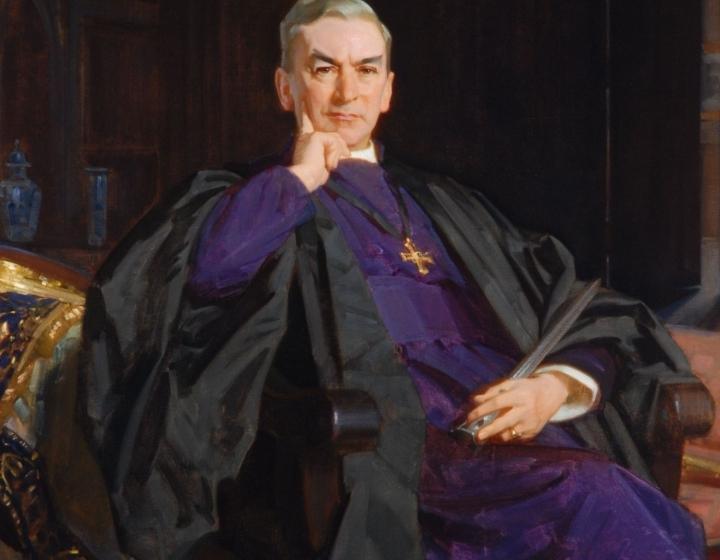

KYNREN, which opens tonight in Bishop Auckland, is a riotous romp through 2,000 years of history, and at its centre is an extremely colourful bishop.

He is the Right Reverend Herbert Hensley Henson, who was as controversial as he was alliterative. HHH reigned at Auckland Castle from 1920 to 1939, and he acts as Kynren’s narrator. The show kicks off with a boy booting a ball through the bishop’s window, and Henson decides to inspire the lad with a history lesson to divert him away from such terrible things as football.

And it is true that Henson had a low opinion of the beautiful game.

He was once in the directors’ box at Feethams, watching the mighty Quakers. When asked how the game was going, he replied: "I don't know, but I understand from all the shouting that the so-and-so's must be winning."

But he was not only anti-football. He was also anti-union, anti-strike, anti-socialism, anti-state welfare, anti-the virgin birth, anti-teetotalism, anti-telephones, anti-coughing in the cathedral, and anti-Hitler.

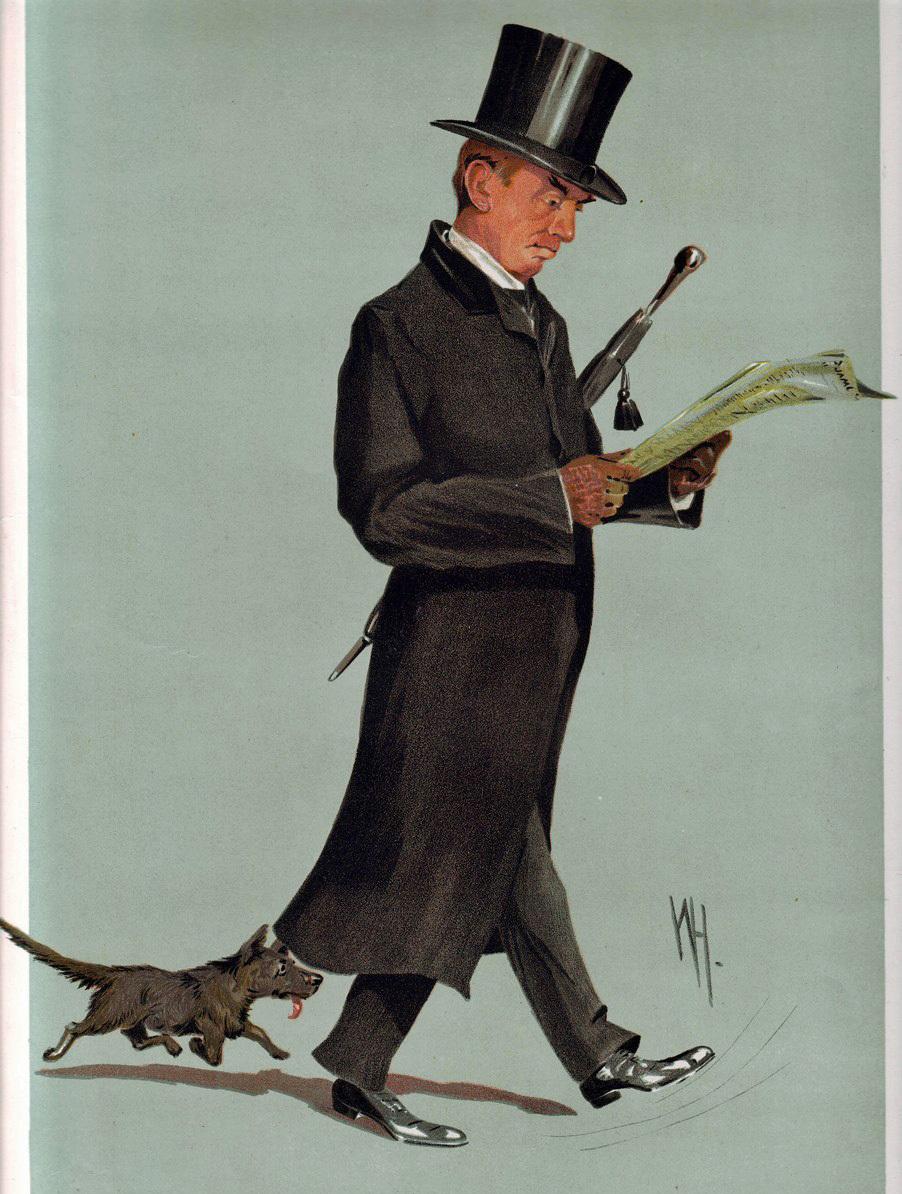

And in return, lots of people were anti him – from the Archbishop of York to the miners of Durham. Following an article in the London Evening Standard in which he had attacked the striking miners, the Dean of Durham, Dr J Welldon, was spotted preparing to address the Durham Miners’ Gala about the evils of drink. The miners mistook the dean for the bishop, and pounced, attempting to wrestle him into the drink of the Wear. Some versions of the story have the unfortunate dean ending up in the river; others say he merely lost his umbrella and his hat – and his dignity – in the scuffle.

Yet Henson also had a deep compassionate streak, caring for the unemployed miners and adopting Durham boys who were born into poverty, paying for their education.

Henson’s own childhood in Kent had been deeply unhappy. His mother had died when he was six, and his father, an evangelical businessman who went bankrupt, banned him from going to school until he was 14. He then rose quickly to be head boy, but ran away when the headmaster wrongly accused him of lying.

Henson excelled at history at Oxford University, where he was noted as an excellent writer and speaker. Such skills could have taken him into law, but since he had been discovered as a youth practising preaching in his nightshirt, he had wanted to become a man of the cloth. Rebelling against his father’s evangelism, he was ordained at the age of 25 and became the youngest vicar in the Church of England.

He became Dean of Durham in 1912, and motored around the county, witnessing the outbreak of the First World War and writing his observations in his diary with a quill pen – over Sunderland, he spotted an early military bi-plane, which he described as a “sinister war-fowl”.

He became increasingly controversial, suggesting that there were doubts about the central tenets of Christianity, about the virgin birth and bodily resurrection. Because of this, when he was promoted to Bishop of Hereford in 1917, his consecration was boycotted by other bishops, including the Archbishop of York.

Although he was isolated within the church, he had friends in other high places, and in 1920 Prime Minister David Lloyd George moved him upwards again, and he became Bishop of Durham. Now it wasn’t his spiritual thoughts that made him controversial, but his political ones.

He was an individualist, and had an almost obsessional hatred of trade unions. He despised strikes, partly because they harmed everyone and partly because he had a recurring nightmare in which he was killed in a streetfight by strikers.

But in Durham in the 1920s, where the coalfield economy was in terrible decline as the Great Strike was following by the Great Depression, his flock found strength through their unions. As his attacks on them became more strident – he even accused miners of shirking – so he was jeered when he visited mining villages and the poor old dean was physically assaulted in a case of mistaken identity.

In 1936, Henson opposed the Jarrow March, calling it “revolutionary mob pressure”, and condemned his subordinate, the Bishop of Jarrow, for supporting it.

But while he hated the unions, for the individual people, he showed great kindness. Although he opposed the state handing them welfare, he helped organise many charitable works to help them. He allowed them to scavenge for coal inside Auckland Park; he sought them out for conversation on his daily walks around the parkland; he stood and watched them playing football.

Because he and his wife couldn’t have children, he did treated the miners’ offspring as his own. He did encourage a few to leave football in the park and enter the castle to see its treasures around which he would weave stories of history – just as Kynren suggests.

But he went further than that, unofficially adopting the poorest Durham boys and paying for their education – an education he had been denied by his father.

Into the 1930s, and Mr Henson again found himself alone. He hated Adolf Hitler – he said he was “amazingly clever with the absurd cleverness of an impudent and quick-witted boy” – and, unlike most churchmen, he thought the British Government’s policy of appeasement was wrong. In fact, he welcomed the prospect of holy war against the “godless barbarism” of the Nazis.

This bishop of contradictions retired from the see of Durham at the age of 75 in 1939, eight months before the outbreak of the Second World War.

But, as Kynren says, he was immediately enticed out of retirement by Winston Churchill who persuaded him to become a canon at Westminster Abbey. Churchill reckoned that this powerful speaker who had been resolutely opposed to Hitler could become an influential voice in stiffening the nation’s resolve.

However, it wasn’t a great success. Due to Henson’s failing eyesight and the darkness of the abbey in the black-out, he wasn’t able to read his sermons very well – and he always wrote them out because without a script, he knew his fiery tongue might run him into trouble. He stood down in 1941, and must have experienced great sadness when his favourite adopted son, Dick Elliott from Durham whom he had ordained into the priesthood, was killed during the war.

Henson died in 1947. He was an extremely curious character. A reviewer of a recent biography called him an “absurd figure”, which is rather harsh, although he certainly had his moments. For instance, he refused to have a telephone installed in Auckland Castle as he did not know how to work it, so his principal assistant, Fearne Booker, was forced to go to the phonebox in the Market Place with an apronful of change to make the calls that kept the castle running.

Miss Booker was Mr Henson’s wife’s live-in companion for more than 30 years, and the bishop did become close to her as he became isolated from his wife by her growing deafness.

In 1987, a best-selling and racy novel, Glittering Images, was published which had the simmering sexual tension between the bishop and the assistant at its core. The author Susan Howatch admitted that it was a work of fiction – but nearly 30 years later, Mr Henson finds himself at the centre of another riotous romp, but he’d probably approve rather more of Kynren.

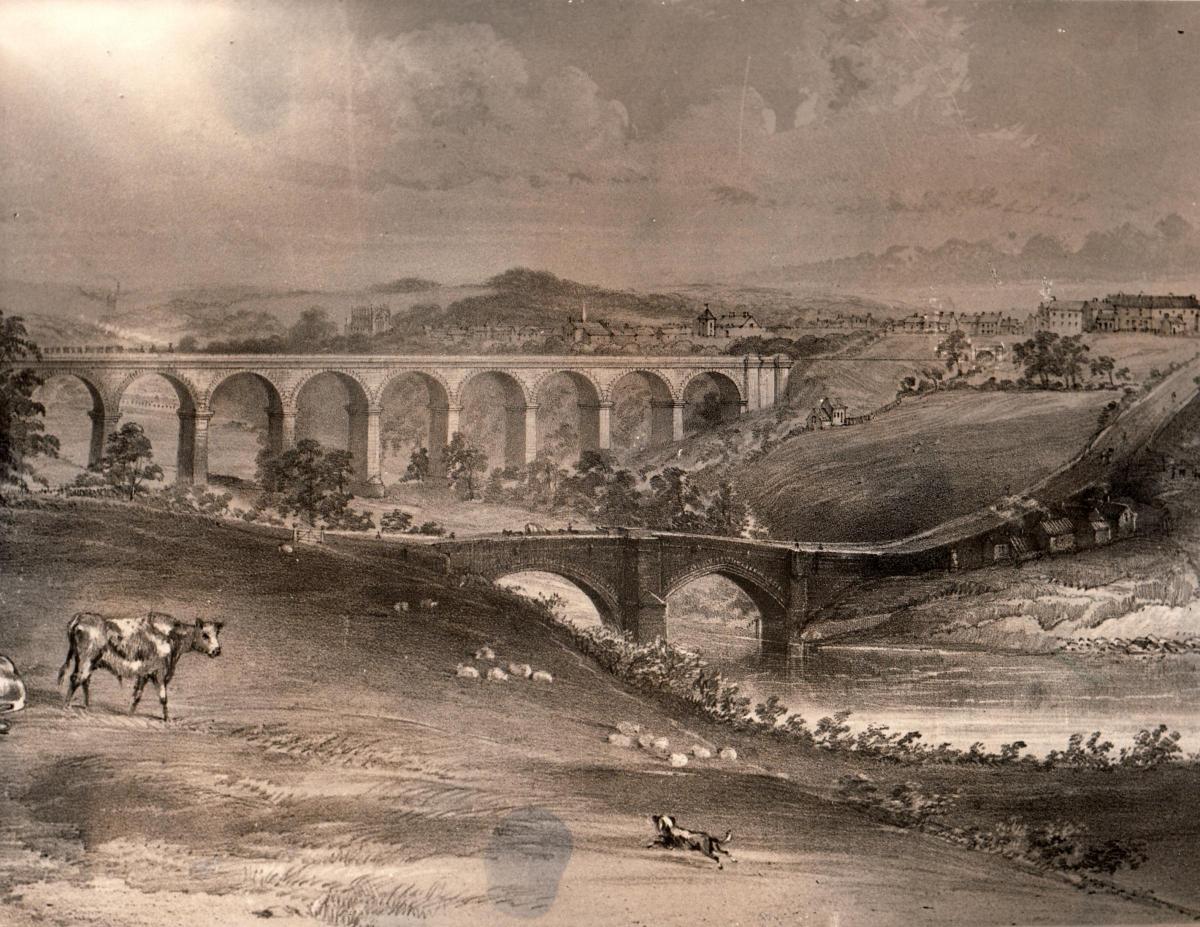

THE Kynren site to the north of Bishop Auckland is best known as the former Eleven Arches Golf Course. Before that it was farmland, and before that, in the dim and distant past, it was a racecourse.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, most towns had a piece of flattish land on which horses were raised. In the Auckland area in those early days, moorland at Hunwick, Etherley and Byers Green hosted race meetings. Usually, they lasted two days, with the horses running up to five heats, with the losers dropping out, until a winner emerged.

It seems that in the late 18th Century, the Kynren site – then known as the Flatts – was settled upon as the favoured venue. A temporary wooden bridge was thrown over the river at the bottom of Wear Chare so that, for a penny, people from the town centre could access the site without having to walk all the way round to Newton Cap.

The Victorian historian Matthew Richley said that the races on the Flatts gave rise to a popular local song.

“It was sung with great gusto by little Sammy and Betty, two well known wandering ballad singers, to the tune of Cappy's the Dog,” he wrote. Cappy was a pitman’s dog, and the tune was written by Tyneside songsmith, William Mitford. The Auckland version went:

“Then come to the races, lets off to the races

And see the fine sights near Auckland town.

There's much fun expected, there's sure to be

The finest horse races you ever did see:

There's Miss Flood and Sledgehammer, the pride of the place,

Will surely shew them some style in the race,

On the banks of the wear, where I'll meet with my dear,

And all the fine lassies of Auckland town.”

But Richley, in his 1872 book about the town, said that racing was not what it used to be.

“The old turf spirit and love of sport which then characterised horse racing has now, we fear, degenerated into that of a system of gambling, and it is well that in the place of those annual local gatherings we now have, in this neighbourhood at least, meetings of a more intellectual character, in the shape of flower shows etc...”

It is believed that during the work to create Kynren, a couple of old furlong makers have been discovered.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here