From The Northern Echo of April 1, 1991

EXACTLY 25 years ago, the first person in the North-East to be jailed for refusing to pay his poll tax was mysteriously freed from Durham Prison having served only four days of his two month sentence.

The poll tax – or community charge, as it was officially known – was a new method of funding local government introduced in 1990 by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government. It was immediately unpopular because everyone paid the same no matter how much they were able to pay.

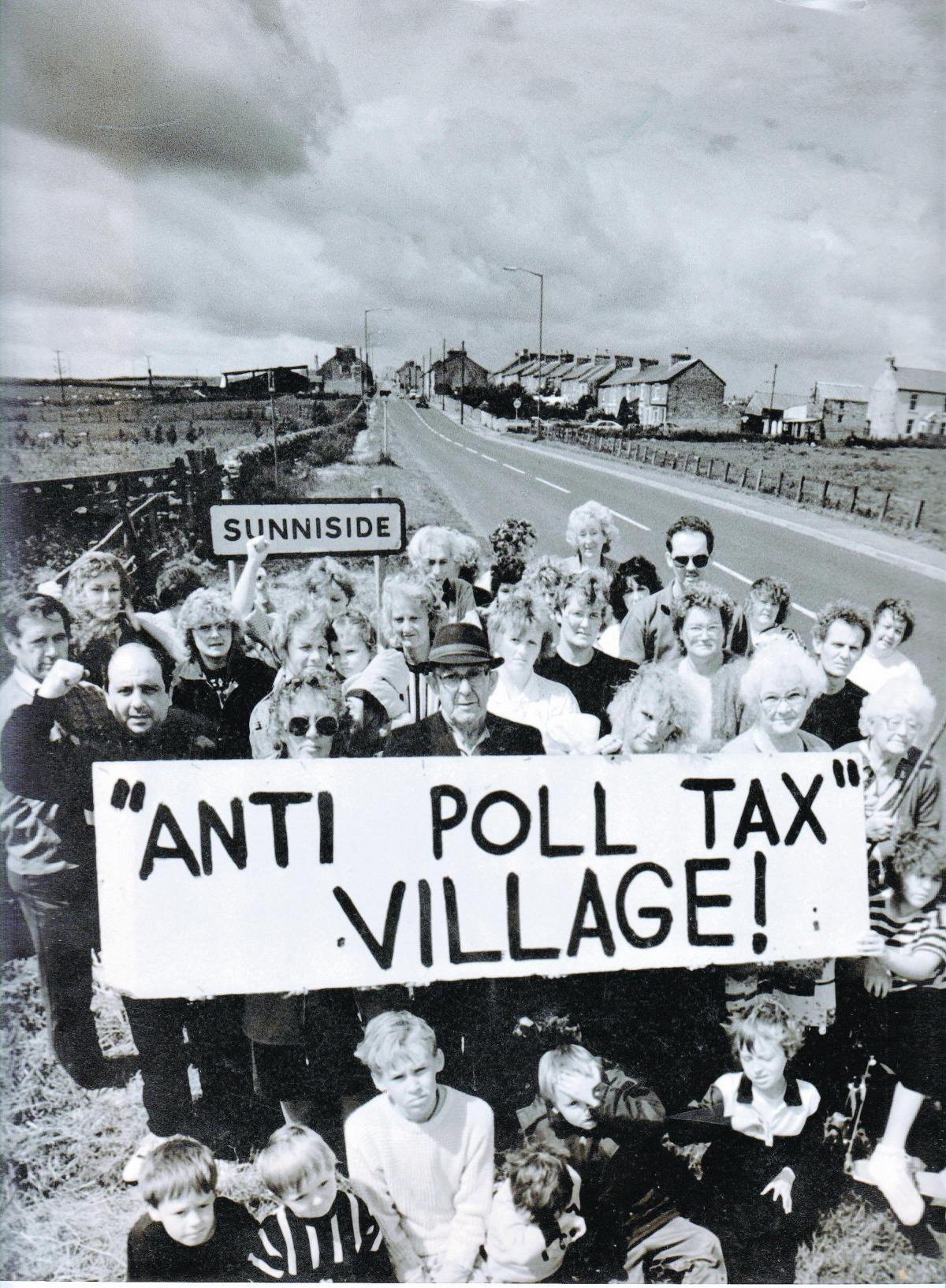

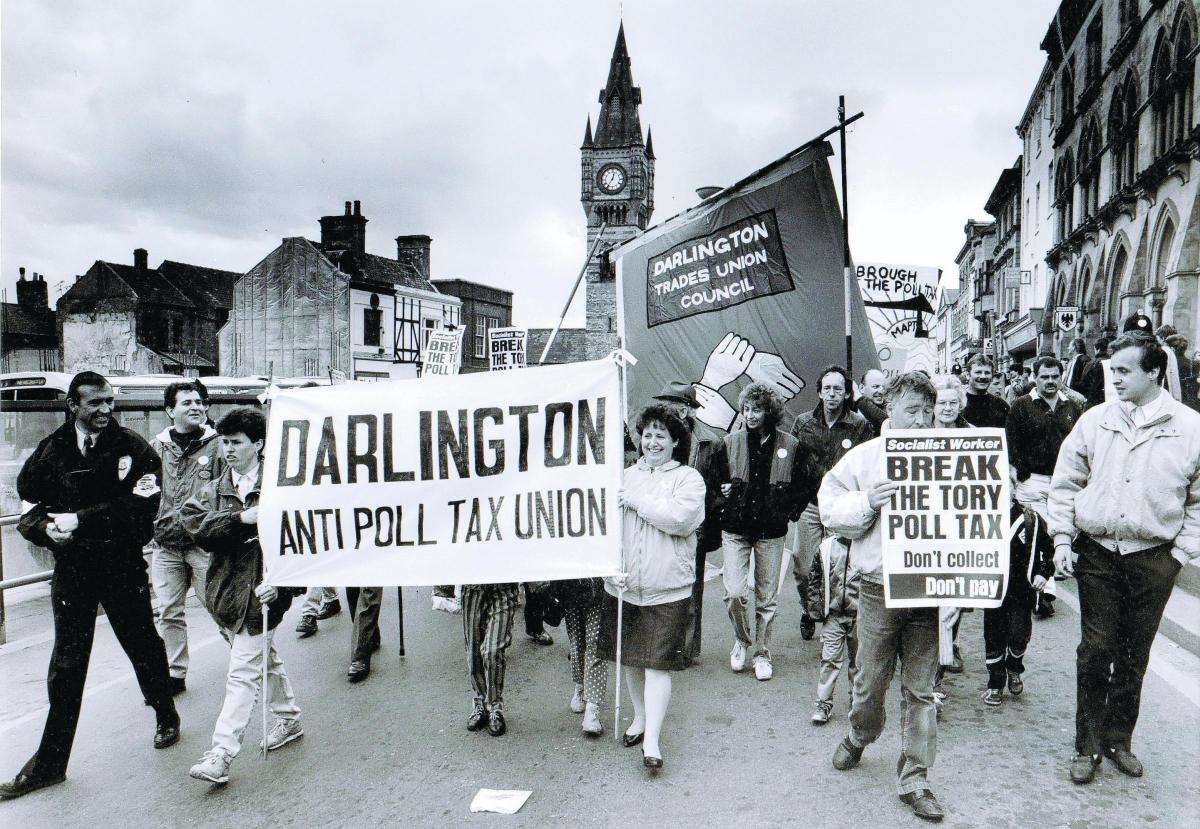

The poll tax protests were largely in 1990. Perhaps the riots of London’s Trafalgar Square are best remembered, although there were less headline-grabbing protests, like at Sunniside, near Crook, where 95 per cent of the 180 adults in the village signed a pledge refusing to pay.

The enormity of the opposition drained support from Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who was forced to step down on November 22, 1990, and on March 21, 1991, Chancellor Norman Lamont announced that from 1993 a new Council Tax would be introduced, which would be based on property values, and so reflecting people’s relative ability to pay.

But for two years, people had to pay the poll tax, and by March 1991, the first refuseniks were being prosecuted.

On March 28, Ian Thompson, 29, of Hebburn, became the first in the region to be jailed. He had failed to pay South Tyneside Council £319.

On March 31, a 150-strong demonstration gathered outside Durham Prison, where he was held. He was, he told them, in “fine fettle”, and he said: "I'm standing firm. Keep up the struggle."

The Anti Poll Tax Federation promised that the demonstration was only the beginning – there would be thousands on the Durham streets by the weekend if Mr Thompson were still incarcerated.

But by the end of the day, his debts had been mysteriously cleared and he was a free man.

"I spoke to Ian on the phone,” said an anti-poll tax campaigner the following day. “He had a can of lager and he's absolutely ecstatic to be free. He is going to work this morning."

Mr Thompson’s family denied that they had stumped up the cash, and the council strongly dismissed suggestions that it had finessed the sums away as he was becoming a political hot potato. It said: “We had no involvement in the freeing of poll tax defaulter Ian Thompson.”

A couple of days later, the civil service confirmed Mr Thompson would keep his job and his story faded from the headlines.

From the Darlington & Stockton Times, March 31, 1866.

A HEADLINE from 150 years ago catches the eye: “Prize fight near Tow Law.”

The report said: “It was rumoured that a prize fight was to take place in the vicinity of the Inkermann Inn, kept by Robert Irvin, at five o clock in the afternoon on Saturday last.” The reporter spelt Inkermann with two ns at the end, even though the area of the town, and the 1854 battle during the Crimean War, was spelt with just one.

The fight was to be between two Irishmen: Peter Kinlin, known locally as “the champion”, and Patrick Mallin.

"The afternoon trains from Berryedge and Bishop Auckland brought great numbers, principally fellow countrymen, into the town, and some had come long distances to witness the set to,” said the paper, presumably meaning the Berryedge at Consett. “Towards five o’clock the streets were thronged with people, who seemed anxious to get a glance at the pugilists."

Word went round that the fight was to be on the low fell – but the police heard it too, and two officers turned at least 500 people from the fell.

"The combatants being determined to have matters settled and not to disappoint their friends, made another attempt, and in spite of the vigilance of the police, they succeeded in getting matters settled in a field near to Thornley, about a mile from Tow Law," said the paper.

“After fighting six rounds, Kinlin was cleared the victor and received the stakes. There had been some brutal conduct on the part of Kinlin's friends, who kicked and otherwise ill used the other combatant.”

The paper concluded: “It is to be hoped that the police will be able to bring the men to justice, that they may be made an example of, and to prevent a repetition of these disgraceful affairs.”

From the Darlington & Stockton Times, April 2, 1966

A PUBLIC inquiry was held at Darlington into whether a three-storey, 24-hour, 60-bedroom transport motel should be built at Barton quarry beside the new A1.

The applicant was Raymond Whitfield who had “refreshment houses” in Croft and Darlington, and the opposition came from existing café owners along the route: in a very different age of motoring, there were said to be at least 12 roadside cafes between Leeming Bar and Barton.

The inspector said he would make a decision in due course. Today, there is a lorry park inside the quarry, but there can be no more than three roadside refreshment houses between Bedale and Barton.

This little story gives us the opportunity to use this picture of the village of Barton, just down the old turnpike road from the quarry. Here, in May 1955, there is a cafe where the village shop is today. Above an archway to the left of the cafe is an unusual face which still adorns the wall – can anyone tell us the story behind the face?

AT the end of March, the Durham Pals received the order to move up into the frontline trenches.

Having volunteered in the heady days of late summer 1914 to do their duty, they now finally had the chance to face the enemy.

On March 25, 18th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry left their billets in the tiny village of Citrene and began the long march to the front.

The Battalion’s war history records how tough that journey was: “The battalion began to move forward in a series of long and exhausting marches.

“The rain was incessant and mixed with sleet, but day after day the spirit and resolution of the men asserted themselves and the battalion marched in nightly without a straggler.

“The greatest possible credit was due to the band which, under the most adverse circumstances and on roads which were trying even for men to walk along singly, played almost continuously and with spirit to the very end of each day’s march."

The first day saw the battalion march through Hallencourt and on to Longpre, where they halted for the night in comfortable billets.

It was followed by “two heart-breaking days to Flesselles, where the party for instruction in the trenches joined us in a snowstorm” and then on to Beauquesne, which would later be Sir Douglas Haig’s advanced Headquarters for the Battle of the Somme.

Private William Weatherley, one of the contingent of teachers who trained at Durham's Bede College, wrote home: “We had expected to escape all snow and slush by going to Egypt but when we left our village for a few days march to the line, snow was very much in evidence. The march was done in stages and we rested at night in barns and lofts in the villages through which we passed.”

They were creeping ever closer to the front. By March 29, they had reached the village of Beaussart, which was just behind the frontline, so close it was used as a British artillery position, with two howitzers stationed at the west end of the village.

It was here that the Durham Pals suffered their first casualty in France. On March 29, a German aeroplane came over the lines to attack the village, aiming its bombs at the artillery position. One bomb exploded close to the battalion, shrapnel from the explosion killing outright Private Arthur Armstrong, 26, of

High Grey Street, Crook, where his parents John and Mary mourned for him.

It would be a taste of things to come.

That evening, under cover of darkness to protect them from enemy attack, the 18th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, silently filed into the frontline trenches to relieve the Royal Irish Rifles.

As dawn of March 30 broke, the Durham Pals were facing the might of the German army across no man’s land.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here