Darlington's largest employer closed 50 years ago this week, severing the town's connection with the railways. This is the story of the last days

APRIL 1, 1966, was “the saddest day of the year”, said The Northern Echo. The last 70 men employed at Darlington’s North Road Shops gathered in the “miserable surroundings” of the canteen for the last rites of a railway industry that had once employed 4,000 people and had built nearly 3,000 locomotives in its 102-year lifetime.

“It seemed colder inside the dismal works than outside where wind and hail turned spring to winter,” said the short report. “There were tears in the eyes of more than one man who listened to the works manager Mr Jack Brown say: “We wish you luck – and thank you.””

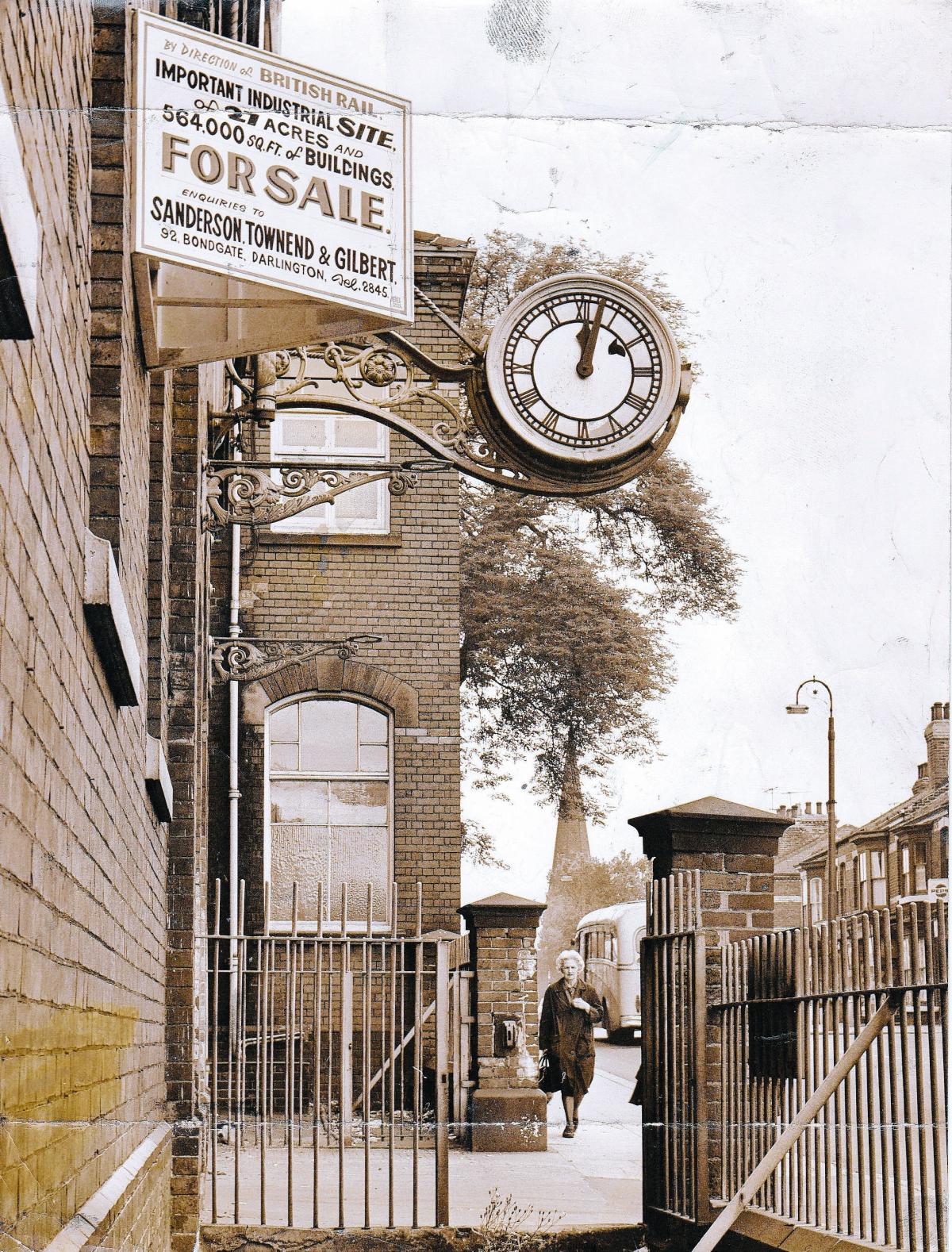

The 23 storemen collected their last wages and their redundancy payments, and walked out through the archway and under the landmark clock onto North Road for the last time grumbling that they were £200 down on what they expected.

It was, said the headline, the end of their life’s work.

They left behind the 40-or-so strong wrecking crew, who were to dismantle the machinery, and the large pack of stray cats which had already made their homes in the derelict outbuildings of the vast 27.5 acre site that had been Darlington’s largest employer.

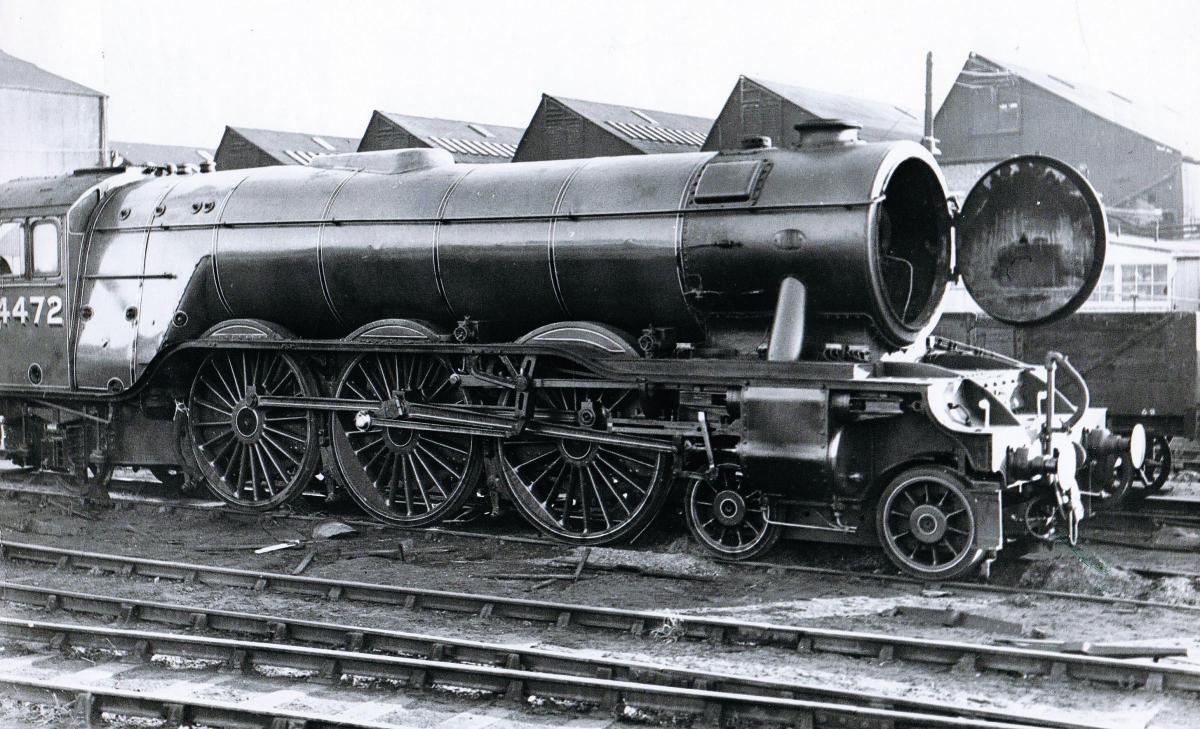

As Memories told last week, the workshops opened on January 1, 1864, to build and repair steam engines. They reached their peak in terms of employment in 1954, with 4,000 men maintaining British Railways’ national fleet of 1,724 engines.

But by 1954, the railways were converting to diesel-power, which put a question mark over North Road’s long term future. Hundreds of thousands of pounds were spent converting the works to the new power source, and between 1952 and 1964, they built 421 diesel locos and 85 diesel-electric engines.

Yet the railways were in a parlous state. Despite millions of modernisation money being spent on them, they hadn’t never recovered from the derelict forced upon them by the Second World War. They were unable to compete with the motor engine – both goods and people were increasingly moving on the growing motorway network.

In 1960, BR lost £42m – and its losses were deepening by the year. In March 1961, the Conservative Government appointed Dr Richard Beeching, the development director of ICI, to chair the British Transport Commission and stop the rot. He was immediately controversial, picking up the same salary in the public sector as he had in the private: £24,000-a-year. According to the Bank of England’s Inflation Calculator, that is worth £462,000 today, and it was a staggering £14,000 more than even the Prime Minister Harold Macmillan earned.

Beeching, who had no transport experience, set to work, and the railwaymen soon realised what was coming down the line. On September 3, 1963, they staged a mass protest against the rumoured closure of North Road. The remaining 2,500 men marched out of the shops in their blue overalls and drab jackets; several thousand more spectators lined the streets.

They gathered in High Row – then the Great North Road – and speeches were made from a platform near the top of Tubwell Row. It was an extraordinary sight (please see over). The mayor, Fred Thompson, said the council would do all it could; one of the union leaders warned that Darlington would become another Jarrow, and the town’s MP, “the bronzed” Anthony Bourne-Arton (Conservative) was jibed, harangued and booed as he urged the men not to be frightened of change.

The Northern Echo was pessimistic. “Dr Beeching’s expensive rejuvenating operation…has so far turned out to be nothing more than the old fashioned axe wielded, moreover, with considerable clumsiness.”

The axe fell just three weeks later: North Road was chopped (2,500 jobs) along with the Faverdale wagonworks (350 jobs). The Stooperdale boilershop’s demise was inevitable (600 jobs) and, on top of the Beeching axe, the Robert Stephenson and Hawthorn locomotive builder off Thompson Street, which had built 1,000 locomotives for the overseas market since 1900, had closed in 1962 (2,000 jobs).

A decade earlier, in their heyday, these railway plants had employed 7,000 of Darlington’s 80,000 population.

But from August 2, 1966, only the stray cats could pick a living amid the dereliction of the town's railway industry.

Darlington was declared a development zone and Lord Hailsham was made Overlord of the North. The town council scurried about trying to find new employers – one it hoped to tempt from the East Midlands was codenamed “Mickey Mouse” but the piece of cheese wasn’t big enough. Chrysler-Cummins did, though, come to Yarm Road to employ 2,000 people and has just celebrated its 50th anniversary.

In 1966, Sanderson, Townend and Gilbert began marketing the 27 acres of North Road for £350,000 “with unlimited opportunities for new and expanding industries or for exploitation as an industrial estate”.

It was not to be. There were no takers. By the end of the 1970s, the site was still not cleared and Morrisons was interested in turning it into Darlington’s first out-of-town supermarket. The Environment Secretary Peter Shore said there was no “shopping need” for such a thing, but it went ahead anyway, and opened in 1980.

Councillors of the time were rather dismayed by the blank brick walls that the supermarket presented to the street, but at least the Potts clock, which had hung over the arched entrance to the workshops since 1894, was put back in its original position.

DARLINGTON, of course, was not alone in feeling the razor-sharp of the Beeching axe. It chopped Britain’s railway network by a third: 5,000 stations, 6,000 miles of track and 70,000 men were all axed.

And by the end of the 1960s, BR was losing £100m-a-year and its passengers had been driven to using cars. It was not a big success.

There are few political points to be scored here. Dr Beeching was appointed by the Conservative government as part of dispassionate desire to involve private talents in the running of nationalised industries – and it was that lack of empathy with railway communities like Darlington that made the Tories so unpopular and it was that lack of understanding of railway users – and future railway users – that made the axe so damaging.

Labour campaigned against the axe, even promising that should the win the General Election in 1964, North Road would win a reprieve. Harold Wilson won, with Labour’s Ted Fletcher taking Darlington from “the bronzed” Mr Bourne-Arton, but nevertheless Labour steamed ahead with Dr Beeching’s plans.

And while North Road was undoubtedly a huge loss, it was certainly not perfect. “The shops were rather a home from home, not the most efficient of places,” said Mr Bourne-Arton. “People who got in there could make a job for their sons, nephews, friends and relations. They were down as craftsmen, but it was a bit phoney – and they knew it.”

There were 22 unions at North Road, and the first strike – over union recognition – was in 1911. When the unions weren’t fighting the management, they were fighting each other – towards the end, demarcation disputes were regular, lengthy, bitter and disruptive.

Memories was once told of a crane driver who wished not to join a union, so his workmates gathered at the foot of his ladder, trapping him high up in his cab and throwing bolts at him. He was only able to come down after the end of his shift when all of his colleagues had gone home.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here