Twas the break of dawn in Flanders and the morning promised bright,

The nineteenth of December, and a lovely day to fight;

The Forty-ninth Division had got orders to stand to

But little did they know just then what they were going to do.

At five o’clock exactly, the sentry gave a start,

For just beyond he saw a sight which touched his softening heart;

Twas the greenish plumes of phosgene gas, and those awful deadly fumes

Were sweeping towards our lines to send our men to their dooms.

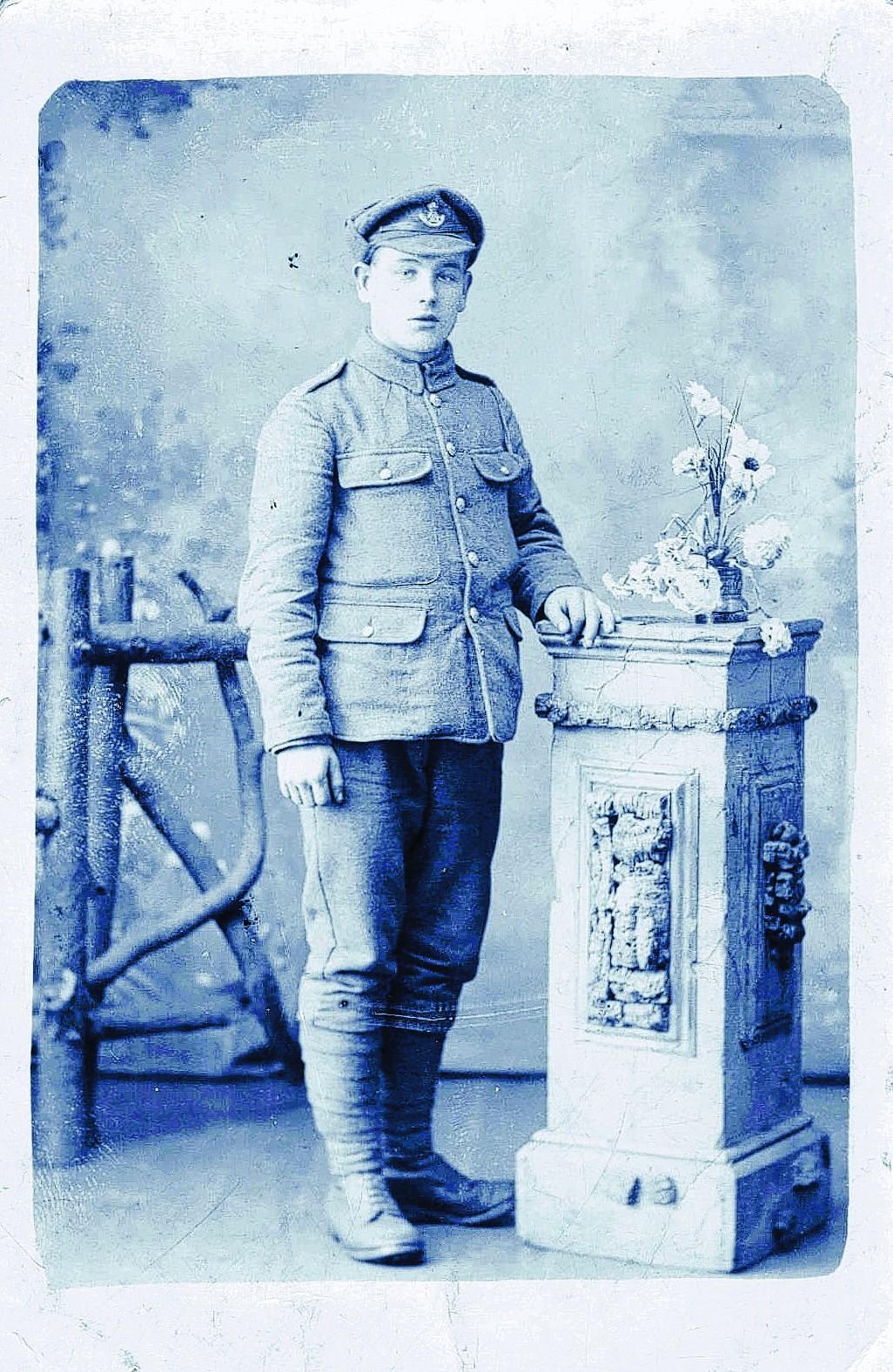

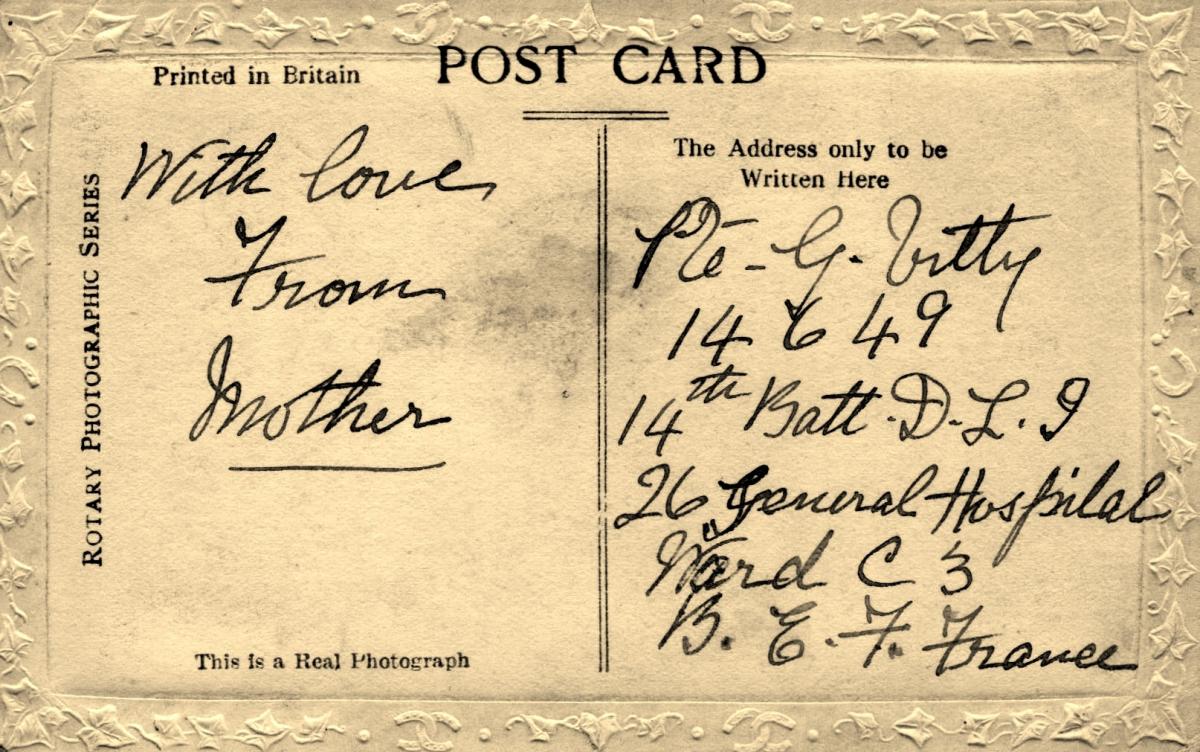

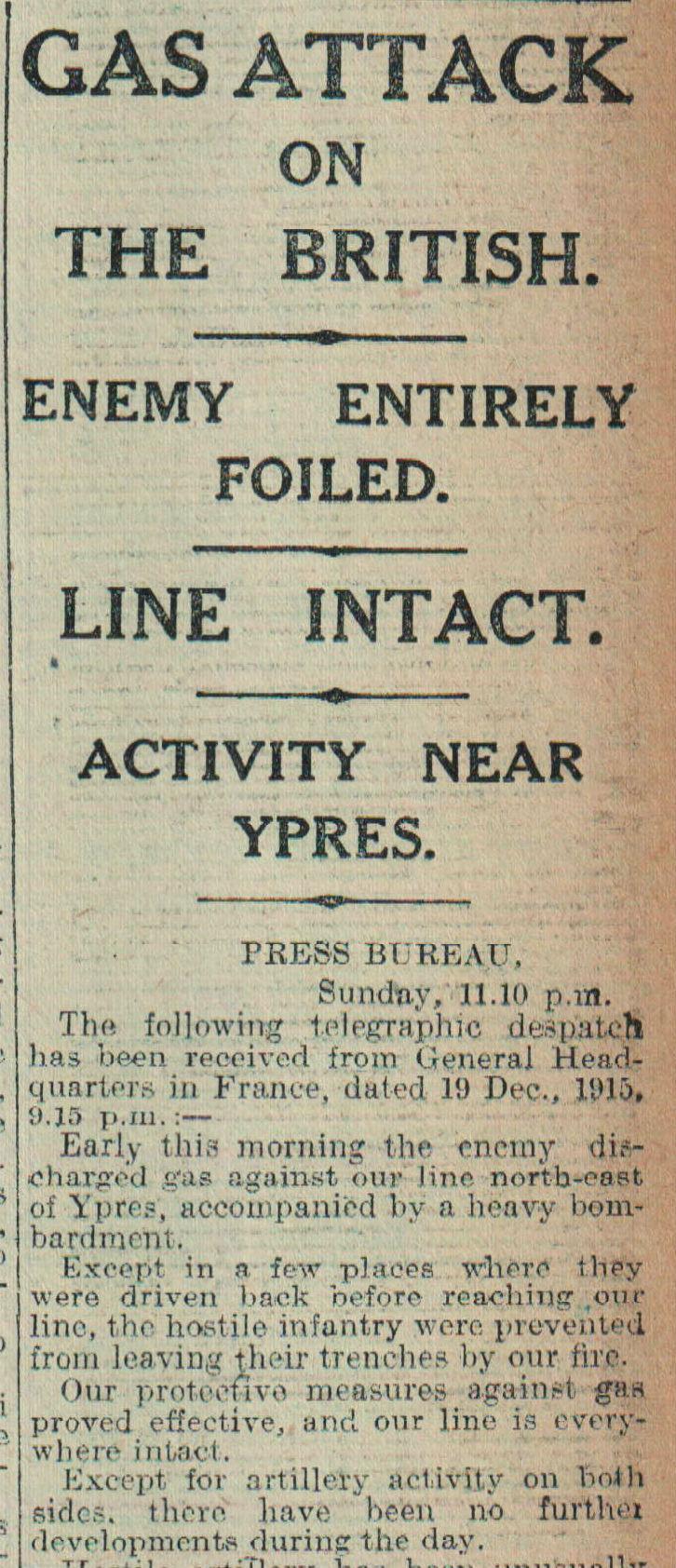

EXACTLY 100 years ago this morning, before the merest glimmer of daylight touched the sky, the men of the 14th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry were in their trenches near Ypres, perhaps dreaming of gentle Christmas church bells at home, when they were violently awoken by klaxons and gongs, pumped and banged by their own sentries.

They were under attack from gas, from a new kind of gas: phosgene, which turned to hydrochloric acid in a man’s lungs and drowned him in his own body fluids.

It was the first time the Germans had used phosgene against the British, and the above lines were written just two days after the attack by stretcher-bearer Pte Alfred Calton. He was with the West Riding Field Ambulance, in the 49th Division, who came to the aid of the DLI.

In fact, Pte Calton may even have saved the life of Pte George Vitty, a miner from Fir Tree near Crook, who brought the poem home as a memento.

In the days before December 19, 1915, the British were aware that a gas attack was possible, as a captured German officer had spilled some of the beans. They also knew that in the earliest hours of December 19, 1915, the wind was in the right direction to assist the Germans.

As the poem says, at 5am, the DLI’s sentries became alarmed by unusual behaviour in the enemy lines: a single parachute light had gone up, followed by red rockets and the sound of hissing, as the gas was released from canisters.

The most dangerous element of a gas attack was surprise, so the sentries quickly kicked up a fearful din with gongs, klaxons and bells to awaken the men so they could pull on their gas masks. Then the British heavy guns kicked in, bombarding the German lines, because a gas attack was usually the prelude to a ground offensive.

The men kept splendid order when they heard the gas gong sound,

To fix on all smoke helmets, the order soon went round;

But some had been too slow to heed, or their helmets had mislaid,

And as the gas fumes caught them, each one a victim made.

Then the guns began to thunder, and the shells began to burst,

Each victim of the deadly gas was seized with awful thirst;

But drinks were out the question for water was not nigh,

And so they lay down in the trench to gasp, and choke, and die.

In the first wave of the attack, the Germans released a white cloud of chlorine – a gas they’d been using on the Western Front for six months. However, its effectiveness had been limited when the British had invented the P Helmet – the sinister-looking gas mask with the two big rounded eyes which was made from cloth that had been dipped in sodium phenolate to neutralise the chlorine.

So, in the second wave about an hour later, the Germans fired shells full of phosgene gas. They landed with a “dull splash” amid the British lines, and released the phosgene, which was much more toxic than chlorine.

However, the British had seen it coming, and for two months had been issuing PH Helmets, where the cloth was also impregnated with hexamethylene tetramine which protected the soldier inside against phosgene.

But – and it is a big but – many of these masks were faulty.

In his seconds of need, Pte George Vitty of Fir Tree found that he had been issued with one that was full of holes.

George had been born at Phoenix Row, Etherley, in 1890. His parents, William and Priscilla, had moved in search of work in the mines – in 1897, for instance, when youngest brother Fred was born, they were living in Wheatley Hill.

The outbreak of war on September 4, 1914, found them living in Institute Terrace, Fir Tree. William was a hewer in the nearby colliery where George, 24, worked as a putter and young Fred, 16, was a pony driver.

Four days later, the brothers walked to Howden-le-Wear station, caught the train to Bishop Auckland and signed up – Fred lying that he had been born in 1895 and so was 17 and old enough to fight.

They were sent to barracks in Newcastle where the 14th Battalion of the DLI was formed, and on September 24, they marched through the city’s streets, crowded with cheering well-wishers, on their way to the station. A train took them to training camp in Buckinghamshire – the first time the Vittys had been outside their native North-East.

The 14th landed at Boulogne on September 11, 1915, and were thrown into battle three days later, near Nielles-les-Ardres.

By December, they were in the trenches near Wieltje on the outskirts of Ypres. On December 17, perhaps aware of rumours of an impending gas attack, George, Fred and five other members of D Company went out into no-man’s land to gather intelligence. But the enemy spotted them, and they became stranded, under heavy fire, hiding in shell holes and old trenches, desperately trying to get back to safety.

They were still there at 5am on December 17 when, before the break of day, the Germans released the first gas and the British pumped their klaxons and banged their gongs. The lads in no-man’s land heard the alarm and hurried to put on their masks.

But George’s had holes in it.

In an instant, he faced an awful choice: stay there and certainly die from the gas, or make a dash for it and probably die from the fire he would attract. He pulled out his whistle and blowing furiously to indicate he was a friend – as opposed to a foe who would approach more stealthily – he rushed through the bullets towards the British frontline.

He dived into the trench, and eventually found some protection – but not before he had inhaled the gas.

Then we medics got the order, we are needed right away,

And fearful were the sights we saw on that terrible day.

There was no volunteering, for not a man delayed,

For picking our smoke helmets up, we dashed upon parade;

We were hurried to the trenches, to get the sick away,

And midst a hail of bursting shells, we had to work all day.

George was one of those Pte Calton came into contact with as he worked all day, evacuating the gassed men to a field hospital.

The DLI’s official war diary noted: “Casualties in the ranks amounted to 149, but would have been lighter if there had not been so many defective gas helmets.”

Twenty-two of the 149 DLI men died. In the wider division, 1,069 British soldiers were incapacitated by the gas, and 120 of them died.

George survived, perhaps thanks to Pte Calton’s treatment, although he was so unfit for service, he was offered home leave. He refused, and in January 1916, voluntarily returned to his company to help out, fetching and carrying and providing hot meals for the men.

In March 1916, both sides agreed a ceasefire near Ypres so that the dead and dying could be collected from no-man’s land. George was acting as a stretchbearer when the enemy broke the ceasefire. The front stretchbearer was killed outright, the casualty was hit for a second time, and George was struck in the right shoulder. He was evacuated once more to a field hospital, where his right arm was amputated.

He was repatriated, and convalesced at hospitals in Dublin, Cumbria and Scotland before ending up in Guisborough Hall. On June 8, 1917, he was discharged from the army as no longer physically fit and returned to Fir Tree. He became a postman and, in 1927, married Nellie, from Wolsingham. The effects of the gas lingered, and he spent much time in Sherburn Hospital, which meant Nellie had to do his post round as well as bring up their family.

However, he lived a long and fulfilling life: he retired from the Post Office at the age of 70, continued as scoutmaster of the 2nd Fir Tree Scout troop until he was 75, and died on Christmas Eve 1979 at the age of 89.

His brother, Fred, was not so fortunate. He survived the gas attack, but was killed near Fricourt on September 18, 1916. His name is on the Thiepval Monument.

And nor was the poet, Pte Calton. The lad from Leeds was killed on the Somme on January 26, 1917. He was only 21, but his little rhyme gives a fascinating insight into what men like George and Fred Vitty of the DLI went through exactly 100 years ago today.

n With many thanks to George’s grandson, John Alderson, who still lives in Fir Tree.

MOST of the 22 DLI members who died in the gas attack are buried in Potijze Burial Ground, near Ypres. One of them, Pte Donald Little, of Fulwell, Sunderland, was only 16 so he, like Fred Vitty, must have lied about his age.

Many of the fatalities came from Gateshead and Sunderland, but they also included Pte Fred Ditchburn, 23, of Browney Colliery, Durham; Pte George Gough, 35, of South Street, Ferryhill; Pte John Hutchinson, 22, of Cassop, Coxhoe, and Pte Benjamin Sedgwick, 27, of Belmangate, Guisborough.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here