ON May 1, 1915, Emily Anderson and her daughter Barbara, who was a month shy of her third birthday, boarded RMS Lusitania at Pier 54 in New York.

Emily was five months pregnant with her second child and she was suffering from tuberculosis. She was returning to her native Darlington, where her parents still lived, in the hope that the better healthcare of home could help her through her pregnancy.

From the rail on the upper deck, Barbara, holding her mother’s hand, scanned the sea of faces down below on the dockside, searching for her father, Roland. He, too, was a Darlingtonian – his father worked as a fireman on the railway and lived in High Northgate – but Roland had emigrated to the US in 1910. He’d found work as a draughtsman and machinist in the Winchester Repeating Arms factory in Connecticut, a business that was booming due to the war, preventing him from joining the voyage home.

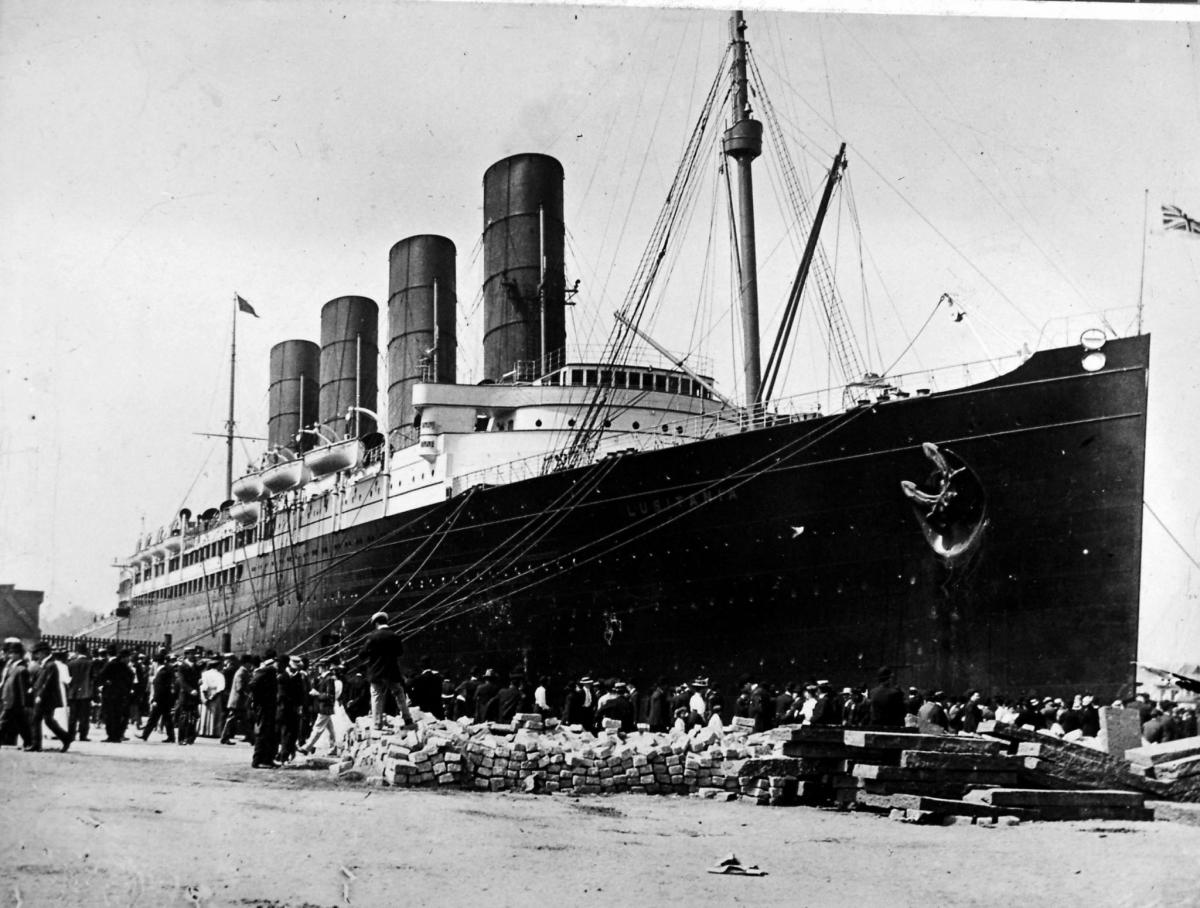

Barbara couldn’t locate him in the crowd, although the Lusitania, the fastest and most luxurious liner of its age, was not full. US newspapers had been reporting that even though it was a civilian ship carrying passengers from non-combatant countries, the Germans regarded it as a legitimate war target. German embassy staff even approached passengers on the dockside to pass on the warning, and even with Cunard cutting the price of second class tickets to $50, 900 of Lusitania’s 2,200 berths were unfilled.

Emily and Barbara were in second class, and as the ship left New York, the ocean was full of friendly warships which would protect it against the new submarine menace.

Most passengers dismissed the German warning as propaganda, yet there was obviously an air of unease on board. For example, on May 7, as they neared southern Ireland, the Lusitania emerged from a dense fogbank as Emily and Barbara joined the queue for the dining room, and an Irish gentleman shouted out: “Look, there’s a submarine! It’s coming towards us!”

Emily later told The Northern Echo: “Everybody laughed, with the exception of a few nervous ladies.”

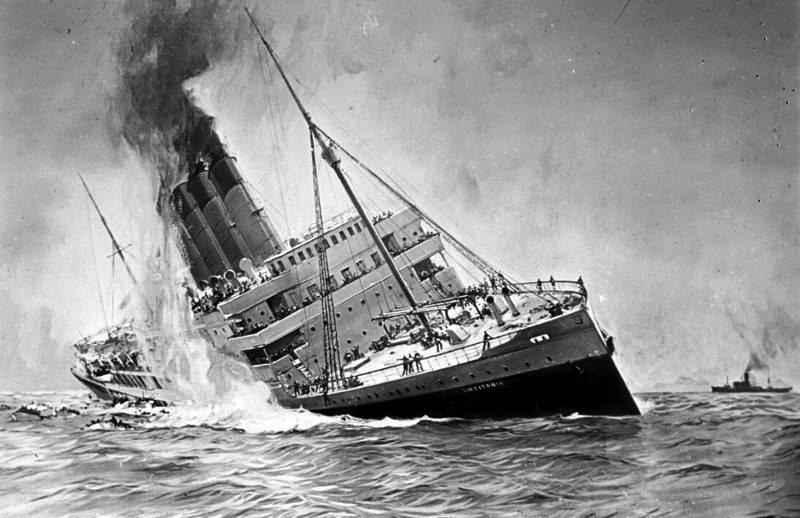

An hour or so later, at 2.10pm, those on deck really did see a German submarine, U-20, emerge from the water about 600 yards away. Lusitania was travelling fast up the Irish coast, so it had time to fire one torpedo.

It hit the liner’s starboard bow, and the noise of its impact was followed immediately by a huge, internal explosion. Within moments, Lusitania was listing sickeningly to starboard.

In the dining room, Emily grabbed Barbara. They left their puddings half-eaten, and hurried out on to the deck which was already at such a steep angle that they slid from one end to the other.

Perhaps fortunately, this brought them to part of the ship from which it was possible to launch lifeboats. Several had already got away, and only one remained.

“It was getting full,” Emily later said, “when one of the pursers who was in it shouted ‘throw the child’, and I threw Barbara into his arms. A little time after, I scrambled into the boat myself and took Barbara again.

“It was only then that I discovered that her right hand was tightly clutching something. It was a silver dessert spoon with which she had been eating her pudding when the first strike of the exploding torpedo shook the ship. She kept it tight all the time and it will always be a memento of the occasion.”

They were in Lifeboat 15, surrounded by the “doomed, piteous cries from hundreds of voices” of people in the water. The men in the boat rowed furiously to get away from the doomed ship, fearing they would be sucked down when the liner went under.

Within 18 minutes of being torpedoed, Lusitania disappeared beneath the water’s surface.

“We saw the suction of swirling water engulph (sic) one body in the gaping mouth of a funnel,” Emily told the Echo. “Then a torrent of filthy black brine shot, like a geyser, from the depths of the funnel and the lady was hurled out into the sea. We picked her up, blackened and dazed.”

After a couple of hours adrift, the Andersons were picked up by an Irish fishing boat, Wanderer, and taken to safety. They were among the 764 survivors. But 1,201 people died.

The Germans protested their right to attack the liner which was contributing to Britain’s war effort and was within the war zone, and the Lusitania, which had not received the expected warship escort when she entered British waters, was later found to be carrying an undisclosed cargo of munitions.

Nevertheless, there was a chorus of condemnation at the murder of unarmed civilians, many of whom were citizens of non-combatant countries. The Daily Express – perhaps not the most impartial of observers – called it “the world’s greatest and foulest crime”, and in neutral America, which lost 128 of its civilians, there was outrage. Tellingly, afterwards the Germans scaled back their attacks on civilian shipping.

Within a couple of days of the sinking, the Andersons made it safely to Darlington and were put up in the home of Emily’s parents – Mr and Mrs Robert Pybus – in Woodside Gardens (we guess this was in the west end of town).

Four months later, Emily gave birth to a boy, Frank Roland, who was never very well. He died, aged five-and-a-half months, with neither his father, still stuck in the US, nor his big sister, Barbara, seeing him.

Emily herself could not shake off the TB. She took a turn for the worse in early 1917, and died in Darlington on March 11, aged 28. For the rest of the war, Barbara was raised by her two sets of grandparents, and she became close friends with a girl called Eileen.

In 1919, with the ocean safer, she returned to her father on board the Lusitania’s sister ship, Mauretania. It arrived in New York on Christmas Day and Roland had a Christmas present waiting for her – a new doll, which she christened Eileen after the friend she had left in Darlington.

She had also left her inscribed dessert spoon in Granny Pybus’ home in Darlington, and it disappeared when the house was cleared after her death – no one in the area has a Lusitania spoon that might be it, do they?

Barbara, who married and had two children, died in Connecticut in 2008, aged 95, the last but one survivor of the Lusitania disaster.

A SMALL contingent from Sedgefield is going over to Liverpool next weekend to pay their respects to an engineer from their village who lost his life on the Lusitania, having joined the crew only three weeks before the ill-fated voyage.

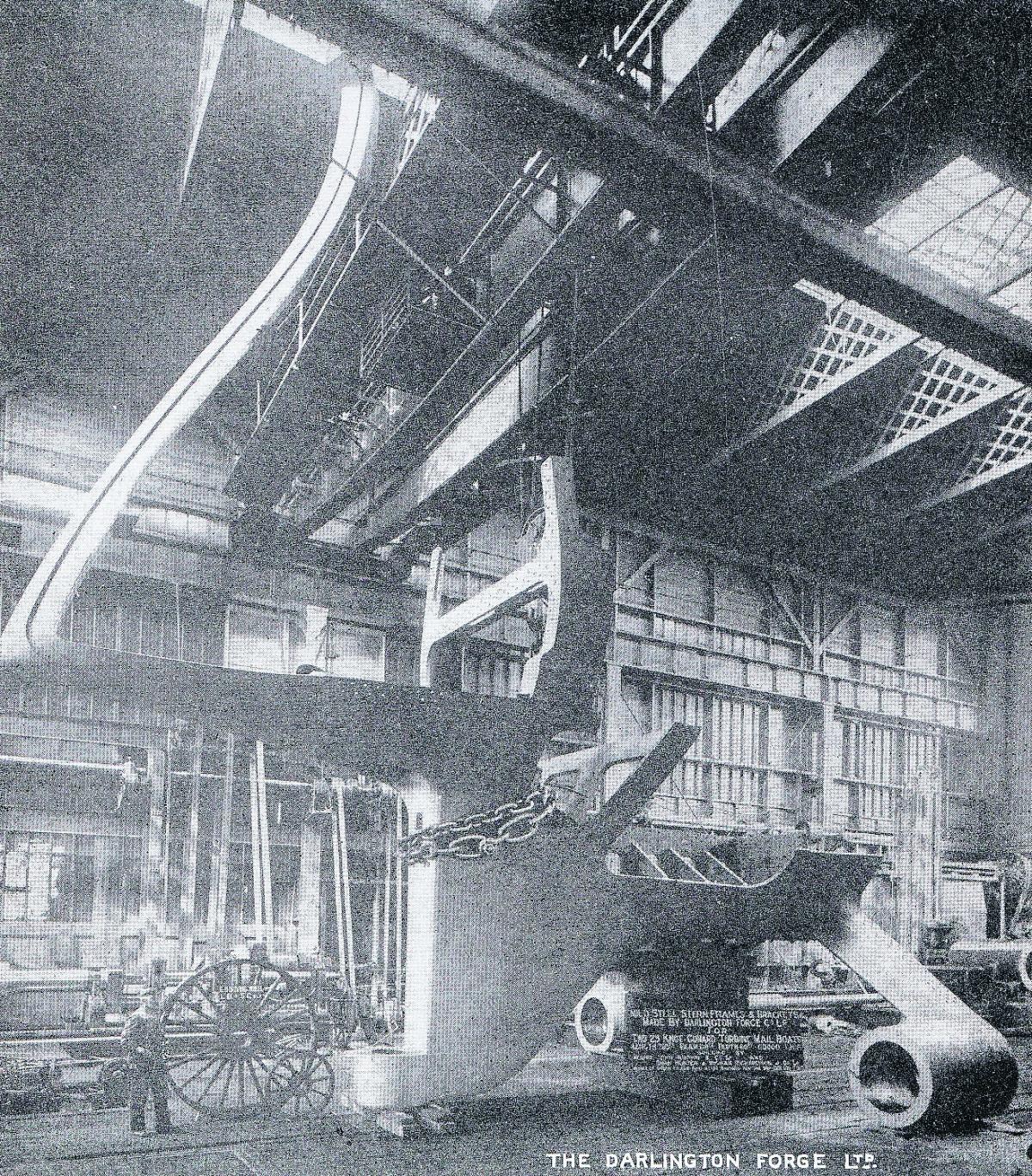

William Affleck Anderson (who was no relation to the Darlington Andersons) was born in Sedgefield in 1881. His father was clerk of works at Winterton, the Durham County Asylum which stood on the road to Fishburn, and his brother worked there as superintendent engineer.

William followed the family engineering line, and became a marine apprentice with Richardsons, Westgarth and Company in Hartlepool. In 1907, he joined the Cunard line, and on April 12, 1915, he was appointed Senior Fifth Engineer on the Lusitania, based at Liverpool, on £12-a-month.

Five days later, aged 33, he embarked on his maiden voyage for New York – it was Lusitania’s 201st crossing. Ship and Fifth Engineer arrived safely on April 24, and began preparing for the 202nd crossing, which left Pier 54 on May 1.

They, of course, never reached Liverpool. Eleven miles off the coast of southern Ireland, Lusitania was torpedoed. The engineer didn’t survive, and his body was recovered from the sea. It was landed at Queenstown, given the reference number 52, and shipped to Liverpool.

On May 15, he was laid to rest in Kirkdale Cemetery, which is where the Sedgefield contingent will find him on Saturday. The party is made up of Town Councillor Chris Lines, and Alison Hodgson from the Local History Society, plus Year Four pupils Charlie Lines and Joe Whitehall from Sedgefield Primary School, which is studying the Lusitania link.

“His name is on the Sedgefield war memorial, and he is one of 42 men who died from Sedgefield in the Great War,” said Cllr Lines. “We will be laying a wreath to mark the 100th anniversary of his death because it is important that we, and the younger generation, remember the sacrifices from long ago which our lives today are built upon.”

The Lusitania records show that on November 29, 1915, the items that were found on William’s body were handed over to his widow, Lillian. She appears to have been living temporarily with their children at a relative’s house in Park Road, Consett.

She received £1 2s 6d which was found in coins in William’s pockets, along with a pair of razors. The Liverpool and London War Risks Insurance Association granted her a monthly pension of £6 7s 3d to compensate for the loss of her husband.

BLOB If you are related to any of the Andersons on the Lusitania, please let us know.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here