THE boys of Bede went to war on April 19, 1915, cheering crowds waving them off from Newcastle station in railway carriages on which had been chalked “Up the Bede” and “Bede v the Kaiser”.

But it was an unequal fixture. Poorly trained and ill-equipped, on April 25, 1915 – just six short, violent days later – nearly all of these Durham teachers and students were either dead, wounded or captured in their first, and only, taste of trench warfare.

Of the 102 Bede boys who boarded those railway carriages 100 years ago tomorrow, only 21 were able to gather a few weeks later and hold up a chalkboard to the camera saying: “Bede – all that was left" (below).

The College of the Venerable Bede was founded in 1841 by the Diocese of Durham to train schoolmasters. Fitness and sporting prowess were part of the college’s ethos, and all students were expected to join the college Volunteer Rifle Company, which was formed in 1875. In 1908, it was re-organised into the Territorial Force in the 8th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry, training in the Gilesgate Drill Hall, out on the Durham moors and at their annual camp.

They were at camp in North Wales on August 3, 1914, when they heard that war was imminent. They clattered home in a train, arriving at Durham station at 1am and marching down to the Market Place where tables had been set out with a meal for them (their officers were refreshed in the Rose and Crown Inn in Silver Street). They spent a last night in their college before being formally mobilised the following day, and sent to the east coast, near Whitburn, to guard against invasion.

These Bede students and recent graduates were in A Company of the 8th DLI, and were commanded by Captain Frank Harvey, head of Gilesgate Council School and a member of Bede staff who was known as “Captain Cardboard”.

Above: the Bede boys larking about at camp just days before the outbreak of the First World War. Herbert Tustin is at the centre of the back row

After eight months of coastal duty and training, the 8th were waved off to the front by the patriotic crowds at Newcastle station. At Folkestone, they joined a troopship, and at Boulogne they were loaded into horse trucks and rattled through the French countryside to Cassel, about 12 miles west of Ypres.

Usually, novice soldiers were slowly introduced to the horrors of the trenches. They would do more training before being placed in a quiet area on the front with more experienced troops to break them in.

But, on April 22, just as the Bede boys arrived at Cassel, the Germans unleashed the first gas attack on trenches north of Ypres. A hellish yellowish-green sulphurous cloud of chlorine was blown over the French troops, causing immediate asphyxiation and 6,000 casualties, and opening a four mile hole through which the Germans threatened to flood. The Canadians beside the collapsing French lines urinated on cloths and held them over their faces as they bravely tried to stem the German tide.

Reinforcements were needed immediately.

As April 23 dawned, the 8th received its emergency call-up.

With the noise of the distant guns getting louder, the Durhams marched to Steenvoorde, where they gathered in a field, were issued with dressings and phials of iodine to treat the injuries they were going to sustain, and those who had not yet done so were ordered to make a will. Then a fleet of red, London double-decker buses carried them towards the guns.

“The moon shone down on a strange scene for us – a faint mist covered the ground,” wrote Capt Harvey. “Our buses swayed and bumped along the uneven pave. The men were in excellent spirits, and sang and cheered like boys out for a school treat.”

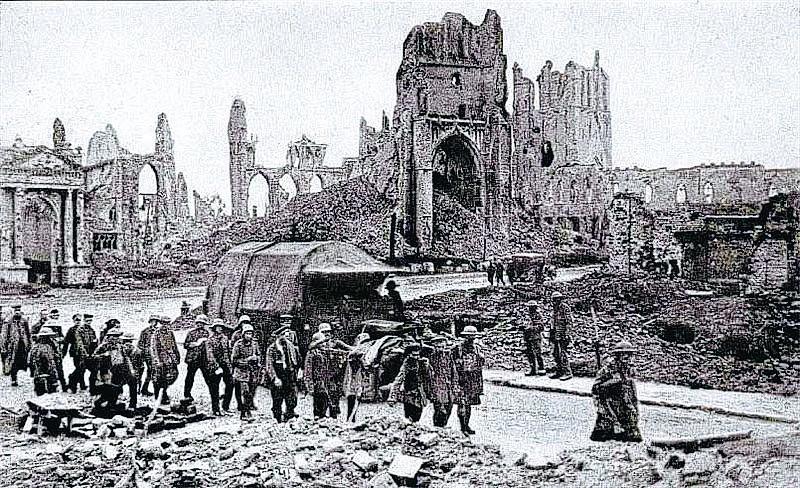

The buses dropped the teachers off near Ypres on April 24, and they marched through the ruined town, its buildings collapsing into the streets, dead humans and horses blocking the roads, German missiles flying overhead, and gassed and injured Canadian soldiers streaming in the opposite direction. Then it started to rain, heavily, soaking their greatcoats.

Leaving Ypres, they marched through the night towards the front, the noise getting louder, the Very lights getting brighter and the stream of casualties turning into a torrent.

Just before dawn on April 25, the 8th DLI stopped at Boetleer’s Farm at the top of Gravenstafel Ridge. Two companies – the Bede boys in A and the Durham Pals in D – were selected to walk down the ridge, picking their way past dead bodies, to the partially-flooded trenches. The shattered Canadians in the trenches were delighted to see them, and showed them how to wet a cloth and place it over the face to protect from gas.

Then the Canadians left, leaving the Durhams – who had never fired a shot in anger – beside the gap in the lines through which the Germans were about to flood.

At 9am, the Germans began bringing up reinforcements. They sent up aircraft to work out the strength of the British newcomers. Excitedly, the Bede boys took pot shots at the planes, giving away their positions. The aircraft dropped glittering paper onto their trenches, marking them out as targets for the German guns.

At 12.30, the bombardment begun, and the German infantry began advancing towards the Durhams.

“These young students and their comrades, totally without experience of the horrors of war, were seeing their friends suffer appalling wounds and deaths. Some collapsed into the bottom of the trench, covering their faces, shaking and crying, only to be encouraged by their fellows to return to the parapet and rejoin the fighting to keep the enemy at bay,” says DLI historian Harry Moses, who is giving a talk today on the Battle of Gravenstafel Ridge.

Without a telephone, A Company had no way of getting word back to headquarters – runners who tried to take messages up the slope were easy pickings for the German guns.

So the toll was immense.

Pte John Huggins, 28, was killed. After studying at Bede from 1905-07, he’d become a professional footballer, playing seven times for Sunderland and Reading, only to return to teaching at Wheatley Hill Council School.

L-Cpl Robert “Barney” Robson, 26, was so badly injured that he died in a German dressing station nine days later. He was from West Hartlepool and had been teaching at Middleton-in-Teesdale Council School when war broke out.

Pte William Arnett, who’d been teaching at Ferryhill Dean Road Council School when the war began, was so badly injured that the Germans captured him, amputated one of his legs and sent him home to Ripon where he died on September 23.

Cpl Joseph Watson, 21, was born in Heighington and lived in Shildon where his father was a railway shunter. At Bede, he’d been captain of rowing, but at Gravenstafel he fell, severely wounded, in a shellhole, crying out for water. Attempts to throw bottles to him failed, so his friend, Pte Joseph Atkinson of New Shildon, crawled out to him.

Unfortunately, Atkinson was killed outright and his body never recovered, and Watson was rescued only to die of his injuries on May 10.

Above: Wooden crosses mark where the Bede boys were first buried at Gravenstafel Ridge

There were similar stories of sacrifice up and down the Durham trenches. So many stories that as the day wore on, withdrawal became inevitable. As dusk began to fall, the Durhams picked their way back up the slope, losing more men on the way.

There were some survivors, of course.

Pte John Barclay, who’d been teaching at West Auckland primary school, made it to the bitter end of the war in 1918 only to die in his hometown of Penrith on December 14, 1918, of influenza.

Two teachers at Corporation School, Darlington, Pte William Bannerman and Pte JH Knaggs both made it through, and Captain Cardboard also survived.

And then there are the extraordinary stories of Pte Weymouth Wash and Pte Herbert Tustin, who were both captured by the enemy. Pte Wash was held until December 1917 when he managed to escape by bribing a German with some bread and soup. He resumed his teaching at Butterknowle and then went into coalmining.

Pte Tustin was held in PoW camp near Munster and, inspired by word from home that “a young lieutenant” was paying too much attention to his intended, Sybil, spent 16 months digging tunnels and trying to cut through electrified wire to escape. He made it out by scrabbling 10ft over the hospital barbed wire fence, lacerating his hands, and then, living off the land, crept through 50 miles of German countryside to Holland where he was returned to Newcastle via the sea.

Sybil, whom he’d met when she’d been teacher-training at the female College of St Hild in Durham, had had no truck with the young lieutenant, and was waiting for Herbert. She accepted his proposal of marriage, and went with him to Middleton-in-Teesdale where he became head of the village school – the only happy result in this terrible fixture between Bede and the Kaiser.

With many thanks to Harry Moses, of Aycliffe, for his help with this article

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here