NINETY feet below Worsall Hall, down impenetrably steep tree-lined banks, flows the River Tees. Today, the hall looks out across the river and over a peaceful, rural scene. Summer fields quietly wave at it from the floodplain on the Durham side.

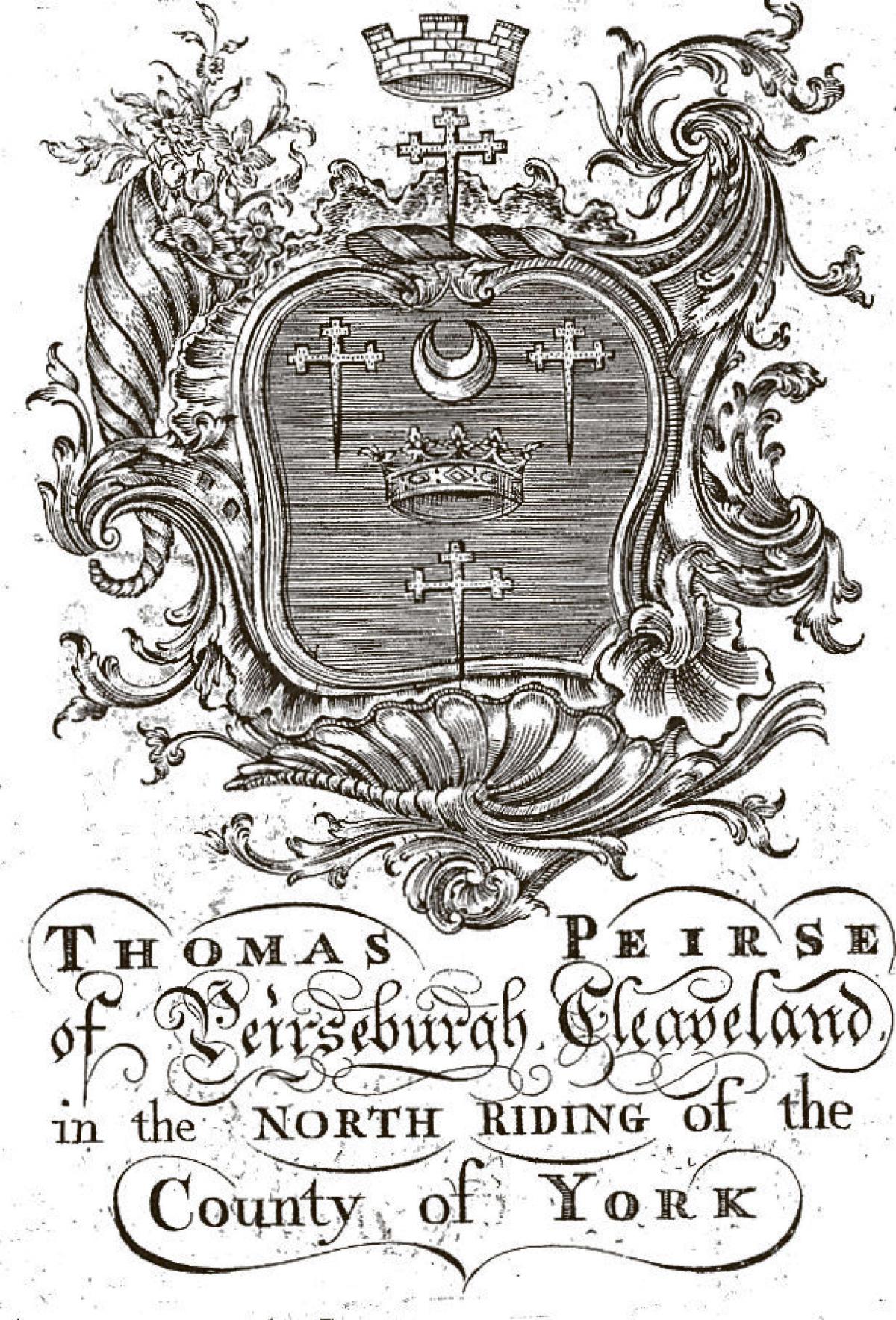

But 250 years ago, it was very different. The man who built the hall, Thomas Peirse, also built beneath it a port – Peirseburgh. Ships, laden with Norwegian timber and tar, pressed to his quayside, and from the landward side came trains of pack ponies carrying Yorkshire's finest produce – corn, cheese, bacon and hams, plus copper ore from Middleton Tyas and heavy pigs of lead from Swaledale – to be loaded aboard for export.

For a generation, Peirse and Peirseburgh prospered. However, it was never an easy prosperity, as Peirse had many battles to fight. And it may not have been a legitimate prosperity, for the respectable village of Worsall is riddled with rumours of smugglers' tunnels.

Peirse inherited the money that he sank into his port from his father, a Yorkshire gentryman and Durham coalowner who lived at Hutton Bonville – another deeply intriguing place, off the A167 between Northallerton and Darlington where today you can pick your own strawberries.

Peirse got the idea for his port from his uncle, Sir William Hustler of Acklam Hall, who built Newport on the Tees to connect his estate to the sea.

Aged 22, Peirse sank his inheritance into the riverfront at Worsall. He was either brave or mad. He decided to create a port which was, as the looping river flowed, 26 miles inland, and in doing so he took on the town of Yarm, three miles away, which for centuries had considered itself the pre-eminent port on the river.

But he could see that the roads into Yarm were in a terrible state. He could see that it would be much quicker, and cheaper, to get heavy goods like lead waterborne as early in their journey as possible.

So in 1732, at the same time as he started work on his hall, he started work on his port, building a stone quayside, a warehouse and a granary. He acquired a sloop which could carry 20 tons of wheat and which had a retractable mast so it could sail under Yarm bridge.

And it worked. Yorkshire Dales leadminers got their minerals to market much quicker, and grocers in Bedale and Northallerton saved £4-a-year by buying in through Peirseburgh.

By 1750, Peirse had three round-bottomed boats that could carry 20 tons each and a bigger sloop, the Cumberland, which could carry 40 tons. Much of his cargo went to Stockton where it was loaded onto sea-going ships, but the Cumberland was large enough for coastal traffic up to Newcastle. In 1738, records show that Peirse sent four shiploads of Yorkshire wheat to Rotterdam; in 1745, he sent a boatload of corn and oats to feed the king's army in Scotland before the Battle of Culloden.

Terraced cottages were built in Peirseburgh for the port-workers to live in, and pubs were built for them to drink in – The Ship Inn at Worsall still bears a watery name despite being landlocked. Parish records show that between 1732 and 1767, there were 93 births, 85 deaths and 45 marriages at Worsall, suggesting that it was a surprisingly large community.

Yet the Tees itself does not really help the sailor. In Peirse's day, it was tidal as far as High Worsall. At high tide there was enough water to sail a boat on, but there were too many bends and too many shallows to allow for plain sailing.

To eradicate the shallows, Peirse dug out the shingle from the riverbed which, he discovered, he could sell to builders.

To overcome the bends, Peirse's ships were haled (CORRECT), or tracked – a rope was attached to them and they were pulled along by men on the bank.

All of which mightily aggravated the people of Yarm. Not only was this newcomer stealing their trade with his port, but he was selling off their shingle from their river, and his men were trampling all over their riverbanks as they hauled his ships.

So they took him to court in 1738. They accused his men "of wanton destruction of gates, styles and fences", of destroying the salmon fishing and of "depasturing" the fields. Peirse lost at York Assizes, and was ordered to use either fishing rowboats to tow his ships up the Tees, or "to warp" them – stout posts were erected on the riverbank around which sailors hauled ropes to move their vessels forward.

Peirse ignored the judgement. At first, the men of Yarm were too cowed to confront his men – he had gangs of eight or ten men hauling the ships, knocking down fences and pushing any protesting farmer out of the way.

But in the 1750s they united behind landowner Thomas Bellassis, the Earl of Fauconberg, and they won another victory at York Assizes.

Peirse countered by taking the case to Durham where, in 1757, he won by claiming that "haling or tracking" a boat was the historic right of any man along the banks of the Tees.

During his 20 years fighting his neighbours, Peirse had been fined £250 and paid out even more in legal costs – large sums, but to him they were worthwhile investments in his lucrative trade.

Peirse was clearly a man prepared to ride roughshod over the law and his neighbours. So what are we to make of the tantalising tunnels of Worsall? There is one, rediscoved in 1958, running from the centre of Peirse's hall down to the riverbank; there is another, rediscovered in 1961, running from the Ship Inn down to the riverbank, and there are rumours of a third running from what is now Peirseburgh Grange down to the riverbank (the Grange was built in Peirse's time as the Maltkiln Inn).

The Customs officials, who collected the duty due to the king on imported goods, stayed in the Maltkiln. Perhaps the tunnels helped Peirse spirit away goods like wine or tobacco that he didn't want the Revenue men to find. Rumours of smuggling abound – right across to Croft-on-Tees where a little patch of grass by the bridge is still inexplicably known as Smugglers Green.

Perhaps it was these nefarious sidelines that allowed Peirse to prosper, but when he died in 1770 times were changing.

In 1747, the road to Yarm was turnpiked – the turnpike trustees were obliged to keep the road in decent repair – and in 1764, the first bridge was built over the Tees into Stockton. Therefore, the trains of ponies could reach the sea-going ships without using the port at Peirseburg.

Plus from 1767 there were plans to build canals and then railways along the Tees Valley, which would render the port redundant. And then in 1771, perhaps the greatest flood of all time had water standing 20ft deep in Yarm. Peirseburg must have been devastated.

Peirse's son Thomas inherited the port and Worsall Hall. In 1779, with debts of £56,000 and assets of only £33,000, he was declared bankrupt.

The hall was auctioned along with the port, which included one ship plus "20 tenements, a good inn and malting, a large well built granary, commodious quays or wharfs, a timber yard and other conveniences for carrying on a very extensive corn, timber and iron trade".

Not that Thomas minded too much. He married Constance, the heiress of Acklam Hall, and, as his great-aunt's will stipulated, changed his surname to Hustler so he could get his hands on her fortune.

At Peirseburgh, lead-dealers tried to revive the trade, but the tide of history had turned against them. In 1808, the Reverend John Graves wrote that "the trade is now lost, in consequence the population is much decreased, the village impoverished and many of the houses uninhabited and falling into decay".

In 1893, Low Worsall church was built out of stones from the quay. In 1935, the last port cottages were demolished, and in 1940, the water board built a riverside pumping house on top of Peirse's warehouses to satisfy the thirsts of the Teesside chemical industry.

So today there is not a lot left to see. But next Saturday, as you wander down to the site of the quayside or as you stand in Peirse's walled garden in the shadow of his hall, with his tantalising tunnel running beneath it, there will be plenty of historical stories growing from your fertile imagination while your eyes are looking at the specialist plants.

- Memories is indebited to Owen Evans of Worsall Hall for his help with this article.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here