Child soldiers in Uganda were forced to decapitate their parents. Football is helping rehabilitate them.

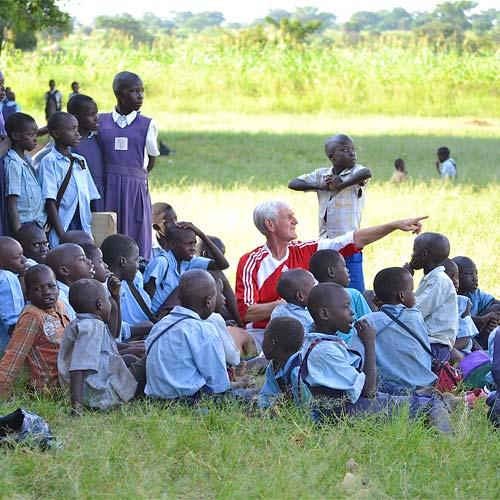

THE picture is utterly, wonderfully compelling. The guy in the Boro shirt and baseball cap is Bill Gates, millionaire tax exile and Middlesbrough’s centre half in more than 300 games in the 1960s.

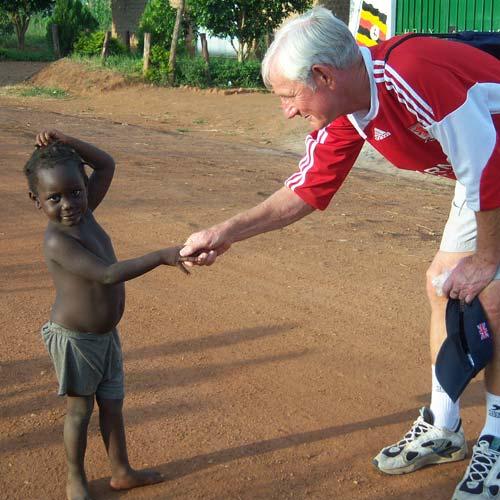

The little lad essaying a passable impression of Stan Laurel is from a tribal village in Uganda.

Bill and his wife Judith were visiting a programme there designed to rehabilitate child soldiers and run by Coaches Across Continents, a burgeoning, football-focused charity started by their son, Nick, and now helping 100,000 youngsters a year.

The little lad’s too young to have known front-line fighting with the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army, but perhaps not by much. Bill also met David, a 17-year-old who several years previously had been forced at gun point to decapitate both his parents with a machete, the alternative that he would be killed alongside them.

“It was so that he would have nowhere to go and be forced to stay with the army,” says Bill. “If I had to describe it in one phrase, it would be life changing. What with atrocities, poverty and what the rebel soldiers got up to, how could it be otherwise?

“Can you imagine the trauma that kid had to go through and still has to go through, yet everyone we met was cheerful and polite, from the youngest to the oldest.”

US president Barack Obama is said to have despatched 100 elite troops to find the Lord’s Resistance leader.

The former England youth captain, who had a knee replacement last year, is also happy to report that he scored four goals in a five-a-side game, though it has to be said that the opposition comprised three ten-year-old boys and two ten-year-old girls and that Bill was referee as well.

“I told him to be careful because the nearest hospital was ten hours away and within a few seconds he’s down on his backside,” says Nick. “He’ll be saying it was six goals soon.”

That he is a lone red shirt amid a sea of black and white – all the smiling faces, as might appropriately be said on Tyneside – is because the Sir Bobby Robson Foundation shipped hundreds of Newcastle shirts to the charity of which Sir Bobby was UK ambassador.

“It’s a cause that deserves support from governments, businesses, the football community and individuals,” said Sir Bobby shortly before his death, and could hardly have said it better.

NICK’S spending a few days at his parents’ place in Castle Eden, between a visit to Africa and flying off to a UN awards ceremony in Monaco at which Coaches Across Continents is one of three sports charities shortlisted for a worldwide award.

A few days earlier he’d had a meeting in mud hut in Uganda, given a live guinea fowl for his trouble. “I’m still not very comfortable at these formal occasions, I’d rather be in the mud hut,” he says.

We meet at Horden – Horden v Whitehaven, to be exact. The former east Durham coalfield has problems of its own, goodness knows, but he’s impressed by the immaculately maintained former Colliery Welfare ground.

Chances of winning the UN award? “It would be the equivalent of Boro winning the Champions League,” he insists.

He’d attended Millfield School in Somerset, had trials with several Football League clubs, graduated from Harvard University, started soccer camps in the US and had a season in 2004-05 as Middlesbrough’s director of business development.

“Genetically I think I’m programmed backwards. I have my mother’s football ability and my dad’s brains,” he says.

Coaches Across Continents began in 2007, its aim to use football as a tool for social development. Next year they expect to be operational in 20 countries, among more than 100,000 youngsters.

“On average we now have a request every day,” says Nick, 44. “The hardest thing is having to say no.”

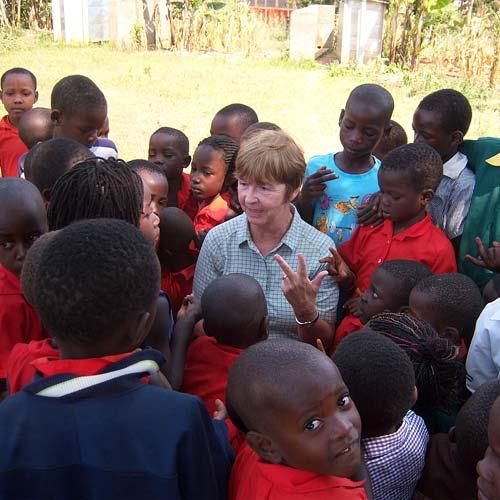

The charity won a Global Sports “Best Newcomer” award in 2009, grows apace. The aims are educational, teaching teachers and coaching coaches. “We are trying to relieve conflict, to use football in a way that is unique. Football is a very powerful tool, but it’s important that we know how to use it.

“Some charities try to create professional footballers, but we’ve no interest in that. We try to help boys and girls grow up happily. The greatest reward is to see a kid smile.”

Though there were offers of support from everyone from the United Nations to Prince Albert, they didn’t win in Monaco. “The funny thing is that they served guinea fowl,” says Nick. “I couldn’t stop laughing; I just wondered if it was mine.”

BILL Gates was a miner’s son from, Dean Bank, Ferryhill, his younger brother Eric a future England international. Judith Curry was a shopkeeper’s daughter from Spennymoor. Both attended Spennymoor Grammar School, had barely noticed one another until the school trip to the Olympics in Rome.

That’s where he bought her a red rose – “the blonde from Shildon had turned him down” – and where they threw three coins in the Trevi fountain.

He was 17, she just 16; within months they were married.

Though eyebrows were raised, the fountain was richly to bless them.

On November 26 the couple they said were too young will celebrate their golden wedding. “A few people will be surprised at that, assuming they’re still alive,” Bill concedes.

Still they’re globe trotting, still holding hands in the pub. “Of course our feelings for one another have changed. It’s a very good thing that they have,” says Judith.

He captained England’s youth team, made his Boro first team debut the week before his 17th birthday, still devoted afternoons to studying accountancy, opened his first sports shop in 1974 and, 13 years later, sold the 12- store Monument Sports chain for £4.4m. They’ve long lived in a beachside villa in the Cayman Islands, returning to England each summer.

He is not, of course, to be confused with the still-richer Bill Gates, he of the Microsoft touch. “People get quite disappointed when they realise I’m not the other one,” he once told the column.

“When I’d finally convinced an air hostess that I wasn’t Microsoft Bill, she wondered rather plaintively if I might be his father, instead.”

Judith went to Nevilles Cross teacher training college, was a head at 29, opened a new school in Middlesbrough at 30, was just 36 when she became a schools inspector in Sunderland, gained a doctorate, became a lecturer at Durham University and was a visiting professor at American universities.

The golden wedding will be celebrated in Australia, most family able to join them but not his parents, 88 and 90, who still live in Staindrop.

“Dad says it’s ower much clart on,” says Bill. “Besides, who’s going to look after his allotment?”

Too young? “Of course we were too young, but I’m still awfully glad that we did it.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here