NONE who sentiently lived through it is likely to forget the winter of 1962-63. If it were bleak down here, or over there, what on earth must it have been like in Tow Law? It was the Alaska of the North; up there they really did get the drift.

The question arises because of a magazine account of a remarkable railway journey to Tow Law, unscheduled and distinctly uncomfortable, seven years after passenger services were withdrawn.

It was mid-February, all roads impassable.

Blizzards were up to the eaves and probably to the oxters.

Fifty years on, it would have been a snow-go area or, worse, a white hell.

Back then it was simply a hell of a challenge.

In Crook, five miles down the hill, 20 or so mainly women workers from the Ramar Dress factory were stranded. Their homes were in Tow Law.

That’s when a message was sent to the railwaymen at West Auckland shed, already fanning steam’s dying embers, seeking urgent assistance.

The line from Bishop Auckland to Crook was still open. The extension to Tow Law, average gradient 1-51, had closed to passengers in 1956 although it still accommodated occasional coal trains.

Though the prospect was daunting, the snow plough special got the green flag. As Gordon Reed puts it in the February issue of North Eastern Express, it marked the end of an era – “like the last mass British cavalry charge in the Sudan”.

GORDON, now 80, was born in Consett and raised in Bishop Auckland where Bill Reed, his father, was secretary of the town’s football club. Gordon was a boilersmith at West Auckland. It was not, he observes, a shed for namby-pambies. “Rather it was an outpost of the Wild West.”

The winter of 1962-63, he recalls was a “dreary, long, cold and dark event, the coldest of the 20th Century”.

Where possible, they kept the locos inside, warmed by insufficient braziers. The water used for washing the boilers froze within minutes, the shed floor like a skating rink.

The train comprised two “Mogul” steam engines, running tender to tender, with two snow plough vans fore and aft. Inside them, cast iron stoves blazed defiantly.

One engine was driven by Geordie Oliver; Gordon stayed behind. Fred “Kitchener” Wood, the steam raiser, was given to observing that the wind was straight from the fell tops at Tow Law. He was about to discover its viciousness.

Following the plough, the snow busters left the shed at 3pm, the day already growing dark and the vans lit by a single tilly lamp. At Crook, says Gordon, the Ramar girls were told to try to find a seat, to hold on tightly and for heaven’s sake to keep clear of the by then incandescent stoves.

The departure from Crook was spectacular, the train joined by the station master and a policeman.

“After Crook West it was just a case of going for it,” writes Gordon.

“The snow was cascading onto the roof of the plough from the drifts. Two particularly severe drifts were felt, but the plough stayed on the tracks.”

At the long-closed Tow Law station, an anxious welcoming party awaited, disembarkation delayed because the platform itself was covered in 4ft of snow.

Whether the stitch-in-time ragtrade girls made it to work the following morning is probably a matter of doubt – but down at wild West Auckland, the snow plough train had returned to station, awaiting whatever might befall.

NONE doubts that it was pretty wild at Tow Law, too. Local resident Charlie Donaghy, then a teacher in Wolsingham, recalls that the school was closed and cut off.

“I went off walking with a couple of cameras, got some superb shots and sent them off to be developed.

They claimed to have lost them, which I doubt, and gave me three free films instead.”

Crook historian Michael Manuel, who has supplied the picture of Tow Law in one of its more extreme moments, remembers it, too.

“Crook Town were due to play Walthamstow Avenue in the Amateur Cup that weekend. We worked all night to clear the pitch and then the referee abandoned it at half-time.

There was hell on.”

Ramar employed 600 people, producing 40,000 garments a week, at a time when more than 1,000 people in the area were out of work. Michael offers recollections from Norma Parkin (“the Mrs Darts of Crook”) who worked there, but lived up on Stanley Hill Top – where the climate was pretty much the same as in Tow Law.

Roads closed, they’d set off to walk wearing the plastic that the dress fabric had arrived in and singing as they went. At Stanley, Windy Ridge, villagers would come out to join in the song.

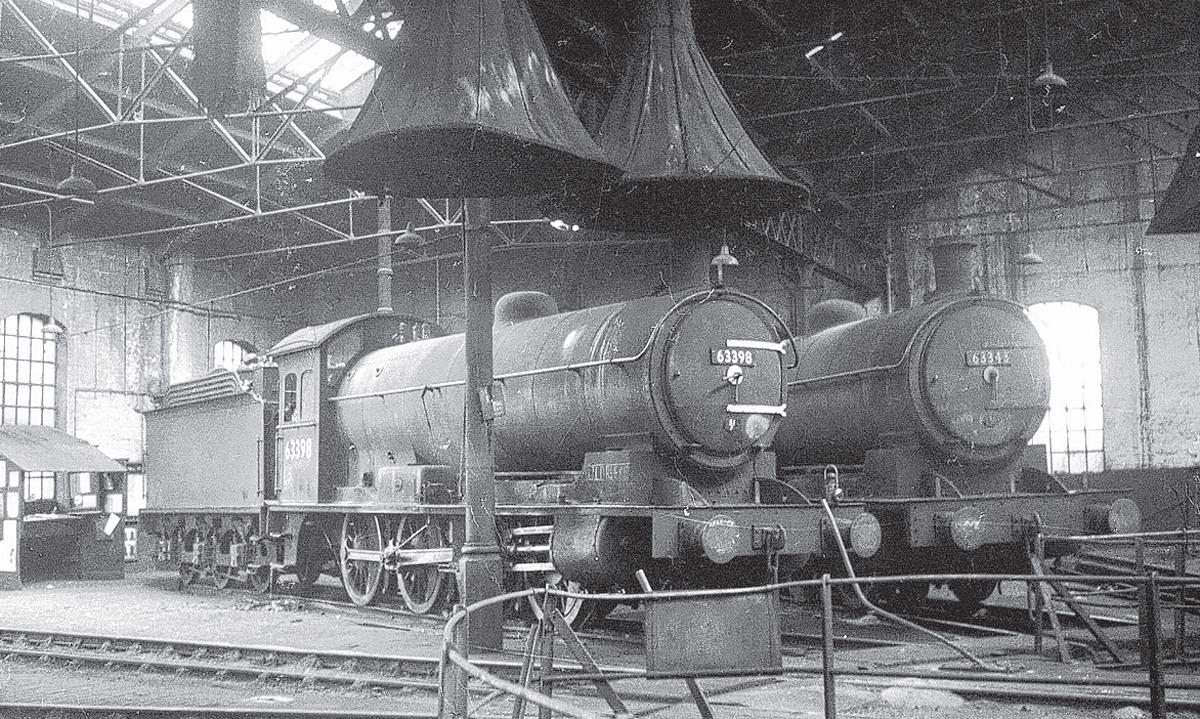

Frank Tweddle, perhaps better known as Darlington FC’s historian, also gives illustrated talks on West Auckland shed – code 51F – where he’d take smashing pictures.

Frank would hitch illicit footplate rides, knows lots of stories, can’t recall the day they rescued 20 freezing damsels in distress. Could it be that Gordon has his lines crossed a little?

HE’S long in Leeds, still volunteering one day a week on the Keighley and Worth Valley Railway and another at the National Railway Museum in York.

Though a little hard of hearing – “all boilersmiths are” – he remains in canny fettle.

“It certainly happened,” Gordon insists. “”It may have been some other time as well, but I’m pretty sure it was 1963.”

Frank Hoggarth, still in Tow Law and at Ramar in 1963, can’t recall the cold comfort special, either. “I usually went in by car.

There’s many a time we had to abandon it and get a lift back with the council man or something, but I don’t remember a train.”

Robin Coulthard, the North Eastern Railway Association’s archivist, has been unable to find an account from 1963, but turns up The Northern Echo front page from January 10, 1959.

Back then the weather was almost as awful, but that appears to have been a “real” train with carriages – and 60 grateful passengers – and not a couple of hastily dragooned snow plough vans.

Was that the same occasion which Gordon remembers, or did the wild West Auckland gang ride to the rescue at least twice?

Memories of crew or passengers very greatly welcomed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here