Rain – and wind – threatened to stop play at a village day with a Stars and Stripes theme.

IT’S ten o’clock on Sunday, July 4. American Independence Day. Though the Stars and Stripes flies full-blown at one end of the village green, there’s a Union Flag at the other.

“We thought we’d better,” someone whispers and quite right, too, for Barton Carnival is essentially, quintessentially, a celebration of the English village.

They’ve asked me to open it, those fair-few words to be followed – they hope – by an open-air songs of praise service before the fun begins.

So what’s the plan? “Oh I don’t know,” says one of the organisers, “it’s on the doo-dah over there.”

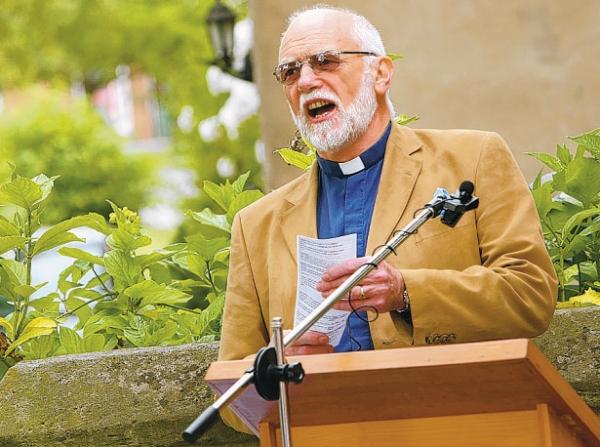

Rain’s in the air, the wind getting up quite conspicuously. “One of the keys to an open-air service is good imagination, so think 75 degrees, blue skies and no passing tractors,”

says the Rev Alan Glasby, who lives in Barton, but is team rector of another dozen parishes thereabouts.

The last bit, in truth, may be an approximation.

It was drowned out by a passing tractor.

Barton’s just about in North Yorkshire, between Darlington and Scotch Corner on what once was the Great North Road – church, chapel, cricket ground, shop, school, two pubs, two-storey village institute and a ford across the beck where once I saw a senior clergyman go so spectacularly Armageddon over Titulars that he may never again have been able to conduct a baptism without being reminded of total immersion.

Pretty perfect really.

Once there was a bad-neighbour quarry, too, so wretchedly ill-managed that in 1965 the folk in Lime Kiln Cottage protested that damn great rocks were being hurled up to 300 yards into their garden and against their garage wall. How much longer before they hit the house, and felled its occupants?

It made a cracking tale, the first proper story I ever wrote, day two – I remind the carnival crowd – of a journalistic jolly that continues yet, whatever they say about sin and first stone.

“Mike must have started his career when he was three,” says Mr Glasby, kindly.

Getting on 100 are gathered beneath the trees outside the Methodist chapel. The service begins with Louis Armstrong singing Wonderful World, followed by optimistic, summertime hymns like Morning Has Broken and For the Beauty of the Earth.

“You’re singing into the wind, you’ll have to sing twice as loud,”

urges Mr Glasby, a keen cyclist who retires, on his bike, next May.

Beb Davies, a Methodist local preacher from High Coniscliffe, delivers a lively and challenging address.

“There’s not going to be any rain,” she insists. “There’ve been so many people praying for good weather, it wouldn’t dare rain.”

She says nothing about the wind, though. It’s getting pretty gusty among the gazebos on the green.

Mrs Davies describes her address as a sermonette, which in Methodism means anything under a quarter- of-an-hour. They do like their 20 minutes, the Non-conformists.

She’s brought a picture of a sadfaced clown, called The Real Me.

“Perhaps he only puts on an act to please other people. Sometimes we laugh and joke when all we want to do is cry.

“Sometimes people really are twofaced.

Not us, of course.”

THE service lasts 45 minutes. By the end they’re battening, Bartoning, down. One tent’s already being dismantled before it’s blasted back towards the exhausted quarry.

Madame Zelda the fortune teller is looking worried. “I told them two days ago that it would be like this and they wouldn’t listen,” she says affably. “I think they thought I was just trying to get out of it.”

She’s doing a brisk trade, nonetheless, bears a serious resemblance to local lad Jimmy Corps, only bustier, bonnier and more brazzened.

There’s face painting, a blues band, a dog show. Pictures of dog breeds are stuck to tree trunks like Wanted posters in the Old West. Lots wear cowboy hats, as if anxious to validate the theme.

The bookstall has lots about cycling.

I contemplate buying something for the rector (who’s a good chap) as a sort of early-retirement present until the gears change and the realisation occurs that it’s he who’s trying to get shot of them all in the first place.

Paul Evans, a Shildon showman, emerges from the Funhouse with a gift, a bottle of Fuller’s Vintage Ale so strong that the bottle has to be kept in a box lest it escape.

“Keep it upright for four days, then enjoy,” says Paul. Sounds fun to me.

At noon I’ve to head for Richmond to talk to some cricket folk – and have lunch – but promise to be back at 3.30pm for the tug-of-war across the beck.

‘YOU missed the high drama,” says the doo-dah lady at the moment of our return, indicating a large tree felled a couple of hours earlier.

“It was really looking dangerous,”

she says. “We had a little parish meeting, talked to a policeman, thought we’d better not take any chances. Fifteen minutes later it was gone.”

It’s hardly rained, though. No more than a few drops, anyway.

Things are packing up, Madame Zelda dragging herself down to the beck, King Willie v Half Moon. Half Moon eclipsed? King Willie dethroned?

The beck’s almost dry, barely enough water to fill a single persons goldfish bowl. Some of Stanley Holloway’s lines from Albert and the Lion roar incorrigibly to mind: They didn’t think much to the ocean The waves were all fiddlin’ and small; There was no wrecks and nobody drownded, Fact, nothing to laugh at at all.

The Half Moon win 2-1. No one so much as gets his feet wet. Health and safety would probably forbid it, anyway.

Cliff Howe, one of the organisers, is looking at the tree. “We’ll sell that tomorrow,” he says.

Cliff rings on Tuesday to report that they’ve raised more than £1,000 for church, chapel, and the institute which his great grandfather helped negotiate from Sir Henry Havelock- Allen, the squire, 103 years ago.

Someone else telephones on Wednesday to report that I’ve won something in the raffle and that it’s waiting to be collected in the Half Moon.

It’s going to mean another visit to the pub. As probably they reflect at summer fetes throughout the land, it’s an ill wind, is it not?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article