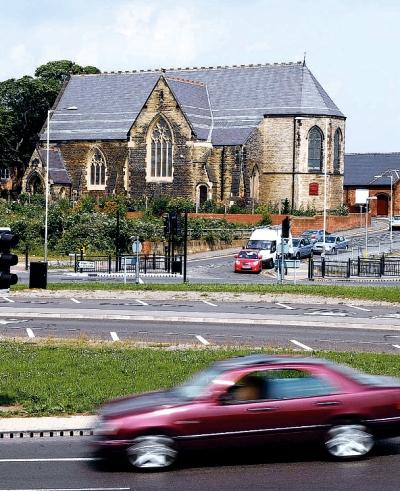

Twenty years ago, St James the Great in Darlington was on the brink of closure. Now, largely thanks to the hard work of its priest, the church is full of vigour.

WHEN Fr Ian Grieves became vicar of St James the Great in Darlington, he arrived with a rather unusual message from the Bishop of Durham. “Don’t worry if you have to close it,” Dr David Jenkins told him.

A little over two decades later, Fr Grieves remains incredulous. “That was his mission statement to me, a 32-year-old about to become a parish priest for the first time. What sort of an incentive was that?”

Mind, you could see the bishop’s point. The church on Albert Hill had an average congregation of 20, a hall that was in danger of falling about their ears and a church building in scarcely better repair.

Traditionally, too, St James the Great was what folk call “high” – high enough to be giddying, so high that they felt emboldened to reject the vicar offered them by Durham.

“Dr Jenkins kept talking about Anglican ethos,” recalls John Bowman, then a churchwarden and among those summoned to Auckland Castle. “He told us that this parish was committing suicide.”

Today, as Fr Grieves celebrates the silver jubilee of his ordination to the Anglican priesthood, everything seems wholly life-affirming. The church could hardly be more vibrant, more full of vim, more greatly in contrast to the oft-dispiriting picture.

The electoral roll is 250, the weekly congregation well into three figures, the worship uplifting, the music magnificent, the incense swinging and the social life every bit as active and as carefully considered.

It’s one of precious few parish churches where Sunday worship remains positively thrilling. Slightly to paraphrase Mark Twain, reports of its impending self-sacrifice seem greatly to have been exaggerated.

“It’s about hard work,” says Fr Grieves. “A lot of clergymen aren’t working. A lot are dross.”

“Fr Grieves talks a lot about not being slapdash,” says John Bowman.

“I don’t think anyone could call us slapdash.”

The parish remains part of the Anglican Communion, part of the Diocese of Durham, but in the porch there’s a poster proclaiming the forthcoming Papal visit to Britain.

Already they’re exploring the socalled Ordinariat, Pope Benedict’s invitation to Anglican parishes chiefly disaffected over the issue of women priests and bishops to seek full communion with Rome.

“We’ve always been high church,”

says John. “All that’s changed is the name of the bishop. We don’t pray for the Bishop of Durham any more. We pray for the Pope.”

FR Grieves is affable, approachable – companionable, even – but still mindful of his position.

None calls him Ian. “I’m not firstly their mate, I’m their parish priest,” he says.

He was a Sedgefield lad, attended Ferryhill Grammar School, became a teacher but felt increasingly drawn to ordination.

His first selection conference rejected him, the bishop suggesting that he might prove himself by working as a volunteer for the Mission to Seamen in Swansea. He received £10 a week.

“I existed on faggots and peas, enjoyed it, but after a year couldn’t expect my parents to support me any more.” At the second selection conference, he was accepted.

“It was grudging,” he says. “They thought I’d be some prissy, fussy high church clergyman.”

He became a curate at St Mark’s in Darlington, moved to Whickham and was invited to come to Albert Hill. Physically it was low level, spiritually flat, ecclesiastically vertiginous.

“We’d not really heard of him. I remember looking him up in Crockford’s Clerical Directory and thinking ‘Oh’,” says John Bowman.

Oh? “We needed a worker and Fr Grieves has given us every minute, works non-stop, visits faithfully.

He’d never have made a married man. He’ll clean the toilets, sweep the floors, never ask anyone to do what he wouldn’t do himself.”

Barry Taylor, a churchwarden who’s been at St James’s for six years, talks of the buzz around the place. “Father has a way of bringing people in. We always say that if you come three times, it’s like there’s a piece of elastic on your back. You’ll always come back.”

Linda Hannant, the verger, was among those already there when the new man arrived. “I’m sure that the church was pretty near closure; now everything is totally regenerated. So much of that is down to Fr Grieves.

Everyone loves him here.”

The vicar seems a bit surprised that they should highlight his pastoral work. “How can you call people special if you don’t even visit them?” he says.

THE 25th anniversary mass was actually on Tuesday evening, followed by what St James’s calls a buffet supper and what others might suppose a coronation banquet.

It was also the feast of St Peter and St Paul. As might reasonably be supposed, the saints took precedence.

Unable to make it – football business, and in June for heaven’s sake – the column invited itself to last Sunday’s 10am service.

“It’ll be dumbed down ahead of Tuesday,” said Fr Grieves. It’s not, of course, but even if dumb and dumber, St James’s services would speak eloquently for themselves.

The only small quibble – about which he, too, may be having words – is that the proper request for silence before the service seems increasingly to be ignored. They’re rabbitting on all sides.

The service is led by Fr Grieves, assisted by Fr John Payne and Fr Ray Burr. “The assistant priests over the years have been an inspiration and a real help,” says Fr Grieves.

It’s the day of the big game, which may explain the chatter. As if to underline his mortality, the vicar confesses that he has no interest in football and will probably spend the afternoon shifting furniture or something.

Fr Payne, in his plain-speaking sermon, talks of the need to juggle different roles. “For a priest to balance his personal life and his priestly life is more of a struggle than many appreciate,” he says.

The choir has more academic hoods than Carols from Kings, the choreography perfect, the music so compelling that Mark Mawhinney, the organist, is applauded at the end.

The months after Easter are what the Church calls Ordinary Time.

There’s nothing remotely ordinary about a service on Albert Hill.

The service lasts 75 minutes, followed by coffee and biscuits in the hall across the road and a chance further to chat with Fr Grieves.

Though already it seems to be a case of “when in Darlington, do as the Romans do”, he insists that they’re not rushing headlong across the divide. “We’re exploring it, there’s no secret about that, but we’re not going to hurry. I don’t see how it’s going to work, but I have to find a way of keeping these people together.

“They need someone to care for them, to nurture them, and that’s not going to happen in the Church of England’s plan for localities for Darlington.

He anticipates spending the rest of his working life there. “I will get this parish to a situation where it is safe, secure and where it has a priest to follow me.

“Whoever would have thought that 20-odd years ago, when they thought we should close it down?”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article