THERE are times when I get unaccountably excited and the rest of the office looks as if I am a little odd. It happened today.

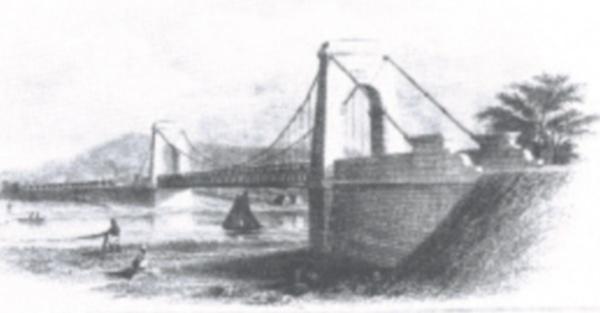

Word reached us that developers had stumbled upon the foundations of the world's first railway suspension bridge was opened over the River Tees on December 27, 1830.

What a piece of history! Particularly as as well as that historic first it was a rubbish suspension bridge with a great story to tell.

I can never understand why the railway pioneers, led by Joseph Pease, opted for a £2,300 suspension bridge (about £200,000 today according to the Bank of England's inflation calculator) when they decided to extend the Stockton and Darlington Railway from Stockton to their new Port Darlington (which became Middlesbrough). Suspension bridges had a horrible habit of collapsing - particularly those built by the man they commissioned, Captain Samuel Brown. (I wrote a history of suspension bridges a while back and I'll dig that out and post it up here, probably on Monday.) This bridge's other historic first is that it was the world's first railway bridge over a navigable river, and I guess that is the answer to my question: unlike a traditional bridge, a suspension does not require pillars and posts which ships could sail into.

The main span of the bridge was 281ft yet the whole structure only weighed 111 tons - yet the pioneers were expecting trains weighing 150 tons to cross it.

In tests, trains weighing a third of that caused alarming wobbles and damage: the deck rose up in the air and the pillars on the Yorkshire side cracked.

John Wall in First in the World quotes Hylton Dyer Longstaffe: "The first trial was made with sixteen wagons, upon which the bridge gave way, ie: as the 16 carriages advanced upon the platform, the latter, yielding at first to their weight, bnecame elevated in the middle so as by degrees to form an apex, which was no sooner surmounted by half the number than the couplings broke asunder, and eight carriages rolled one way, and eight another - the one set onward on their way, and the other back again."

They discovered that if they used chains to keep the wagons 27ft apart, this distributed the weight more evenly on the bridge and it didn't pitch and toss quite so alarmingly.

Still one driver is said to have been so scared that he refused to stay inside his locomotive when it went over the bridge. Instead, as he approached the bridge he reduced the engine's speed so that it was travelling at walking pace. He jumped out of his cab, sprinted across the bridge and then waited for the heavy engine to catch up with him on the safety of the other side.

After 14 years of anxiety, the railway gave up on the suspension bridge and Robert Stephenson built a more traditional bridge supported by cast iron girders.

We shouldn't mock too much, though, and this is what always impresses me about those early days of the Stockton and Darlington Railway. No one had ever done anything like this anywhere in the world. They were taking enormous leaps into the dark. They could only find out what worked by discovering what didn't. Such bravery and willingness to push back the boundaries of knowledge and experience is worth getting excited about.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here