The home fires burn still in Reeth, a wartime headquarters for soldiers whose motto was ‘Only the enemy in front’.

REETH’S tranquil in the seductive summer sunshine, a chimney or two gently smoking skywards, the dray wagon assuaging the Buck Inn’s thirst all that disturbs the early afternoon peace. It hasn’t always been so quiet in that glorious Swaledale village.

During the Second World War it was home, first, to evacuees from Gateshead and Sunderland, later to hundreds of soldiers from the RASC, RAMC, Royal Engineers and, most memorably of all, the men they called the Reccies.

They were the Reconnaissance Corps – motto “Only the enemy in front” – formed into the Reeth Battle School and commanded for much of the time by Major John Parry, who brought his beagle pack with him.

Now those extraordinary days are to be remembered by the commissioning of a plaque outside what is now the upmarket Burgoyne Hotel but then was the commandeered Hill House, Battle School headquarters.

For all concerned it was quite an education.

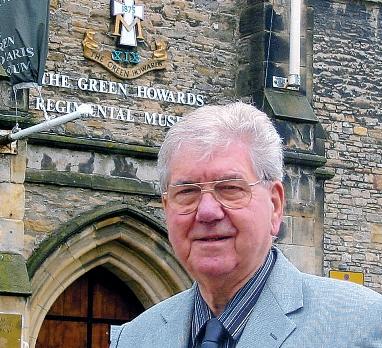

“I’ve got to 72 and still they’re not recognised in any way up here,” says parish councillor James Kendall.

“Most people in Reeth probably know more about the Hartlepool monkey than they do about what happened here during the war.”

The council, keen to back him, hopes to unveil the plaque on Armistice Day. “They were the Commandos of their day, all of them gave something, some gave everything,”

says James. “It’s right that Reeth should acknowledge them before all our generation is gone.

“People today tell their kids to be careful on the roads but back then we were growing up with Chieftain tanks and Bren gun carriers all over this little village.

“We knew there was a war because all our young men had left, but we didn’t know that a village full of Reccies wasn’t normal until they’d gone.

“If it hadn’t been for those boys, we might have had an army in jackboots and grey uniforms instead.”

KEITH JACKSON, a retired Methodist minister, was around 12 when the Reccies arrived, also recalls how – after the Dunkirk evacuation – the RASC had to march the 25 miles from Darlington railway station to Reeth and collapsed, exhausted, on the sunlit green.

“We weren’t scared of the soldiers, rather we emulated them. We’d make uniforms out of brown paper, rifles out of wood. If we needed barbed wire, we’d pull up a few thorn bushes and crawl through those.”

Some still recall the route marches up to Arkengarthdale Moor, the Reccies lined up four or five abreast for 100 yards along the top road, Major Parry as ever cracking the whip.

They talk of the assault course by the side of Arkle Beck – the Reccies named locations like Burma Road, Smoky Joe’s Cabin and Bridge of Sighs – the exercises with live ammunition and Very lights, the nightly mock battles that illuminated the sky like fireworks.

Keith remembers that they’d pile out of Sunday School, still in sabbath suits, and head for the handover- hand assault course across the Swale. The result, and the occasional immersion, was inevitable.

Major Parry once ended up in hospital, it’s recalled, after a similar fall from grace. “They’d do all sorts, often overturning their dinghies into the Swale, the fastest flowing river in England,” says Keith.

“I don’t know how they survived.

They reckoned that Major Parry was a bit mad. Probably it helped to be.”

Barbara Buckingham recalls that her family adopted the Reccies’ cat, called Minniehaha, when the Battle School finally closed. Family cats have carried the name ever since.

“They just never seemed to be still,” says Keith Jackson, “always jumping about, always doing things at the double. They really were the front line. They had to learn how to bash through anything.”

The officers were billeted at Cambridge House, up on the Arkengarthdale Road – “a bit exotic,” says James Kendall – the NCOs at Hill House. The local kids did pretty well out of it.

“We’d always be stopping by the sergeants’ mess, getting a bottle of pop or a lump of slab cake,” says James. “No one in Reeth went hungry when the Reccies were there, but I wonder the poor troops got any food at all.”

They’d have film shows under canvas at Woodyard Farm, concerts in the Conservative Club which had become Home Guard headquarters and is now the Memorial Hall.

Keith’s father was in the Home Guard – “I still remember his rifle in the corner of the house”. He himself became a corporal in the school cadet unit. “It wasn’t that I was military, just in the spirit of the thing.

I’d go marching with the Reccies in Richmond, sometimes be a bit cheeky and wear my uniform to get into their shows.”

Barbara Buckingham remembers the shows, too, recalls Reeth’s “indignation”

when some became a bit too risque for the family audience they’d invited.

She also remembers the minor damage inevitably caused to civilian property during military operations – “informal, amicable compensation arrangements were made, usually involving a bottle of whisky.”

The Battle School disbanded soon after the war finished. Sixty-five years later, some still keep in touch.

Some married local girls. “Top of my head I can think of at least three,”

says James Kendall.

Reeth, lovely Reeth, returned to blessed normality. The home fires burn still, the serenity disturbed only by the dray lorry, assuaging thirst at the Buck.

Lion-heart who knew when to back off

RECCIES’ commander John Parry, born in Ireland in March 1921, died while fishing for salmon on the River Spey 81 years later. He appears to have been quite a lad.

“A character? Oh most definitely,” says James Kendall.

Called up in 1939 with the rank of second lieutenant, he’d become a major when posted to Reeth Battle School in 1943.

Parry also knew of a pack of foot beagles in Sheerness, Kent, that urgently needed a new home. He approached his commanding officer at Catterick – Col Billy Whitbread, he of the brewing family – and gained permission to bring the hounds.

His Daily Telegraph obituary, May 12, 2002, records that the only way he could move them was by public transport. Parry packed the pack into a London taxi to Kings Cross and bought 16 “dog”

singles to Darlington. The hounds lived behind Cambridge House, in Reeth.“I expect he went out for a few foxes with them. You certainly knew they were there,” says Keith Jackson.

Parry’s Reeth duties, says the Telegraph, were performed with great vigour. “His organisational skills and flair for using a combination of high explosive and live ammunition, provided vital training for young soldiers preparing to face the dangers of battle ahead.”

War over, Parry got a job with Whitbread’s, achieved senior status before taking a post with Conservative Central Office. He was awarded the CBE.

He remained a country sports enthusiast. On one occasion – it’s said – he was in an apparently empty farmyard when he heard a noise from behind an unusually high stable door and, on further exploration, came face to face with a large and not especially friendly lion.

The man who lived by the maxim that none was in front but the enemy beat a hasty and doubtless prudent retreat.

Signat’ure pitch

THE stirring tale of the Reccies’ crew was picked up – if not magnetically, then at least methodically – at a brass band concert in Reeth Methodist church.

There’s a story there, too.

Leyburn, next dale down, has had a band – on and off, high notes and low – since 1841. When George Lundberg resurrected it seven years ago, they had five pieces of music. Sixty per cent of the recruits could neither play an instrument nor read music.

Such was the score.

Now they’ve 43 members, plenty of youngsters, 1,723 pieces of music – they bought Horden Colliery band’s library when that folded – have new jackets that alone cost £10,500 and a swiftly growing reputation.

George is both conductor and catalyst.

“An inspirational teacher,”

someone says.

Earlier this month, they marched the South Stanley banner into Durham Big Meeting, 6.15am start from Low Row, played a Salvation Army compilation in front of the balcony at the Royal County and brought a tear to many an eye.

“We’re a community band,” says George, 62. “The dales community has been very supportive of us.”

He’s a retired teacher, also conducts the united parish choir, plays the organ and voluntarily edits the smashing little Reeth Gazette, a monthly magazine.

“He’s wonderful, one of those people who just holds the community together,”

says Keith Jackson.

The July Gazette has a picture of young James Hutchinson, ingenious fancy dress winner at Arkengarthdale sports. He’s an oil slick or, more properly, “How BP brought oil to US shores”.

Acoustically, Reeth chapel’s fine.

It’s space that’s the problem. If not quite of grievous bodily harm, there’s a serious risk of a thick ear from a trombone slide.

They’re in good order, including George’s daughter Emma – principal cornet – and Freddie, her six-weekold son.

Freddie Lundberg? The name didn’t mean much to George, not much of a football follower, but it would to Arsenal fans. We love you Freddie, because you’ve got red hair… They’re terrific, everything from Robbie Williams to Wilson, Keppell and Betty, from Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White to Wind Beneath My Wings.

Freddie’s briefly wakeful, makes his presence heard, is soothed by Old Man River and thereafter just keeps rolling along.

The band’s first CD was Overt’ure, a nod (of course) to Leyburn’s river.

The second, Signat’ure, was recorded over a weekend in Arkengarthdale chapel. They sell a few after the concert, tenner apiece, hope to sell a lot more.

Details of that and of how the band plays on, at leyburnband.com THE concert was to raise a few bob for Reeth chapel, still energetically led and promoted by 80-year-old Keith Jackson, a water engineer until ordained in 1986.

Visitors sometimes outnumber locals.

“Last month I gave the bread and wine to 28 Roman Catholics,” he tells last Wednesday’s gathering.

“I’m not sure if the Pope knows about that.”

Methodism, not least in the Darlington circuit, faces a singularly challenging future, however.

There’ll be much more of that next week.

IT would thus be remarkably churlish not to mention the ever-excellent cream teas available at Ingleton Methodist church, between Darlington and Staindrop, on the next four Saturdays from 2.30pm to 5pm.

“Warm fellowship, too,” promises June Luckhurst.

LAST week’s column grumbled that an otherwise memorable dining car journey on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway had been slightly, metaphorically derailed because the locomotive at the front – no fire in its belly – was a diesel, called Charybdis.

Charybdis was a mythical sea monster, operating in treacherous tandem with another called Scylla. If Scylla didn’t get you, Charybdis would. It was a rock and a hard place.

Paul Dobson in Bishop Auckland draws attention to a song called Wrapped Around Your Finger by The Police – “a popular beat combo in the late Seventies and early Eightis”

– which includes the verse:

You consider me the young apprentice

Caught between Scylla and Charybdis,

Hypnotised by you if I should linger

Staring at the ring around your finger.

Paul has even offered to sing it.

The offer has politely been declined.

…and finally, a note from Shildon lad Bob Whittaker, who became a familiar face on both Tyne Tees and breakfast television and now runs his own television production company from Alnmouth.

Bob’s wife Marrisse, a former Byker Grove scriptwriter, has for the past six months been developing a virtual granny website, hoped to launch in September but – alarmed at reports that bus passes for Over 60s are to be scrapped – has now started an online petition. Details on virtualgranny.com

Bob fails to declare an interest.

The former Auckland Chronicle cub now qualifies for a bus pass himself.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article