Fifty years ago, the Oriental Museum in Durham City opened to help language students understand different cultures. Today, the museum houses collections of international importance enjoyed by schoolchildren, students and public alike. Steve Pratt pays a visit.

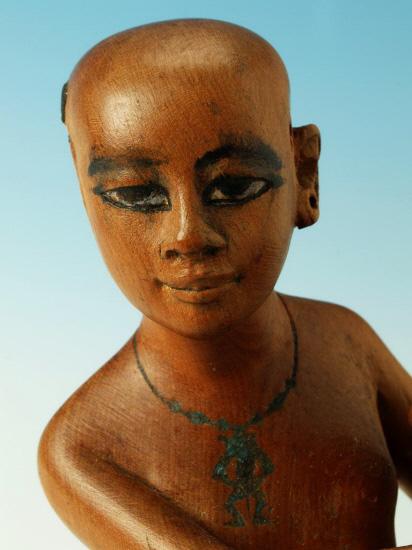

CURATOR Craig Barclay talks about her as if she’s real. “She’s absolutely beautiful. She’s travelled pretty extensively and regularly to exhibitions. I think she’s one of the most beautiful objects to survive from the whole Ancient Egyptian period,” he says, gazing at the little wooden servant girl in her exhibition case at Durham’s Oriental Museum.

She arouses interest whenever she leaves there because her features include tiny pieces of ivory, causing her to suffer the indignity of being inspected by customs officials enforcing export restrictions and legislation on the possession of ivory.

For the moment, she’s back home in her case, awaiting visitors celebrating the Oriental Museum’s 50th birthday, on Friday. Originally planned as a resource for teaching and research for Durham University’s School of Oriental Studies, the museum now annually welcomes not only students, but thousands of visitors from all over the world.

Mr Barclay proves a fascinating and informative guide as we tour the Elvet Hill museum, which, as the name implies, is built on a hillside.

This has led to an unusual tiered layout for what’s home to more than 23,000 objects from Egypt, the Near and Middle East, China, Japan, India, the Himalayan region and South- East Asia.

The story of the museum is linked to that of the university. “In the post-Second World War period, the university became more heavily involved in the teaching of oriental studies,” he says. “Part of the reason for this was obviously the events of the war had flagged up the need to have a core of people trained in the language and cultures of the Middle and Near East. The result was a huge expansion in the teaching of oriental studies.”

Professor William Thacker, first director of the School of Oriental Studies, believed that students couldn’t understand the language without understanding the culture in which it was spoken.

Taking a broad view of oriental studies, the school began collecting material to support the language teaching. Temporary space was found in the colleges, until the late Fifties when the momentum increased to create a permanent musuem. In 1957, the Lisbon-based Gulbenkian Foundation donated £60,000 – at the time the biggest grant received by the university – to build the first of three planned phases.

The Gulbenkian Museum of Oriental Art and Archaeology, as it was then known, opened its doors on May 28, 1960. It was sited in front of the school’s building, Elvet Hill House, and the original plan was to build two similar modules linked by walkways and Japanese gardens.

Funding has never materialised for those.

Admitting the public was something of an afterthought for what was essentially seen as a teaching museum, but has become increasingly important. Today, it’s very much a multifunctional institution with a collection of international importance that supports the university’s teaching, welcomes thousands of schoolchildren annually and is a tourist attraction, too.

Over the years, the museum has changed with the addition of a mezzazine level to house the Marvels of China displays. There’s a constant refurbishment of showcases and reinterpretation of objects to ensure the treasures are seen at their best.

All of which makes the museum “incredibly unusual”, says Mr Barclay. “We really don’t have any direct competition in the UK. The other thing to remember is that our collections are quite outstanding. We have two with ‘designated collection status’ – a collection of Egyptology and Chinese art and archaeology – so that places us in the premiere league of UK museums.”

Negotiations are under way with a major museum in China to send them an exhibition of Chinese material made for the western world and unavailable in China itself. Two years ago, a hugely successful exhibition of Egyptology was sent to Japan.

“Our eyes are constantly on the rest of the world. We raise the profile of the university far afield, as well as that of Durham and the North- East in general,” says Mr Barclay.

FIFTY key treasures will be highlighted in the book being published to mark the museum’s 50th birthday. “Art workers, academics and other contributors will see things that are familiar to us through fresh eyes. There are always new things to learn. One of the things about working in a museum is you never know it all,” he adds.

Much of the Egyptology exhibition came from the 4th Duke of Northumberland’s private collection, one of the finest of the 19th Century.

“He didn’t so much buy material in Egypt itself but from auction sales in England. But he had a very discerning eye and, as a senior member of the aristocracy, a very deep pocket which allowed him to put together an absolutely fantastic collection. He bought very, very well – particularly material with fine inscriptions because he was very interested in languages”.

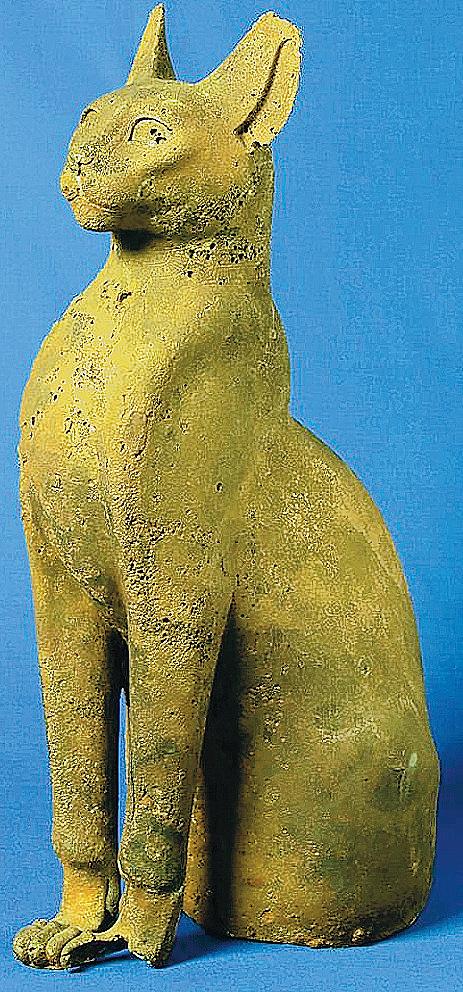

Mr Barclay shows me a lifesize bronze cat, created as a sarcophagus, which contained the remains of a mummified cat inside when discovered.

“That’s slightly gruesome but doesn’t stop it being beautiful. There is another very famous cat, but I prefer ours. It may not be as glitzy, but then it’s not restored.”

Much of the Chinese ceramic collection came from Malcolm MacDonald, son of Ramsay Mac- Donald, and a politician and diplomat in his own right. “In the post-war period, he was Britain’s main man in East Asia. He fell in love with Chinese pottery and collected very, very skilfully. He ultimately became Chancellor of Durham University, and when the time came to find a home for his collection, perhaps it was inevitable it would come to us.”

Only a fraction of the museum’s collections can be on show at any one time, although more is being made available to the public on the internet.

Nothing, however, beats getting close to the objects. We pause by a cabinet housing a sword owned by a king of the headhunters in Malaysia. “Looks like it’s done quite a lot of business,” remarks Mr Barclay, surveying this lethal weapon.

■ The exhibition, Seek knowledge, even as far as China, opens to the public on Saturday and runs until September 26. Events, workshops and family activities will run throughout the summer. For details, visit durham.ac.uk/oriental museum or phone 0191-334-5694 The Oriental Museum is open 10am-5pm Monday to Friday, noon-5pm at weekends and on bank holidays. Entry £1.50 adults, 75p children (five-16) and over-60s, and free for children under five and students.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here