HIS book on North-East football has twice been named among the top 50 sports books of all time; two of his cricket books have won the MCC/Cricket Society’s top annual award.

Now the polymathic Harry Pearson, a man who can turn a phrase like Lionel Messi turns a defender, has focused his ever-observant gaze upon bike racing in Belgium, specifically in Flanders where it’s a regional obsession.

The courses are often cobbled, always discursive. Wriggle like a worm with a tummy rash, he supposes.

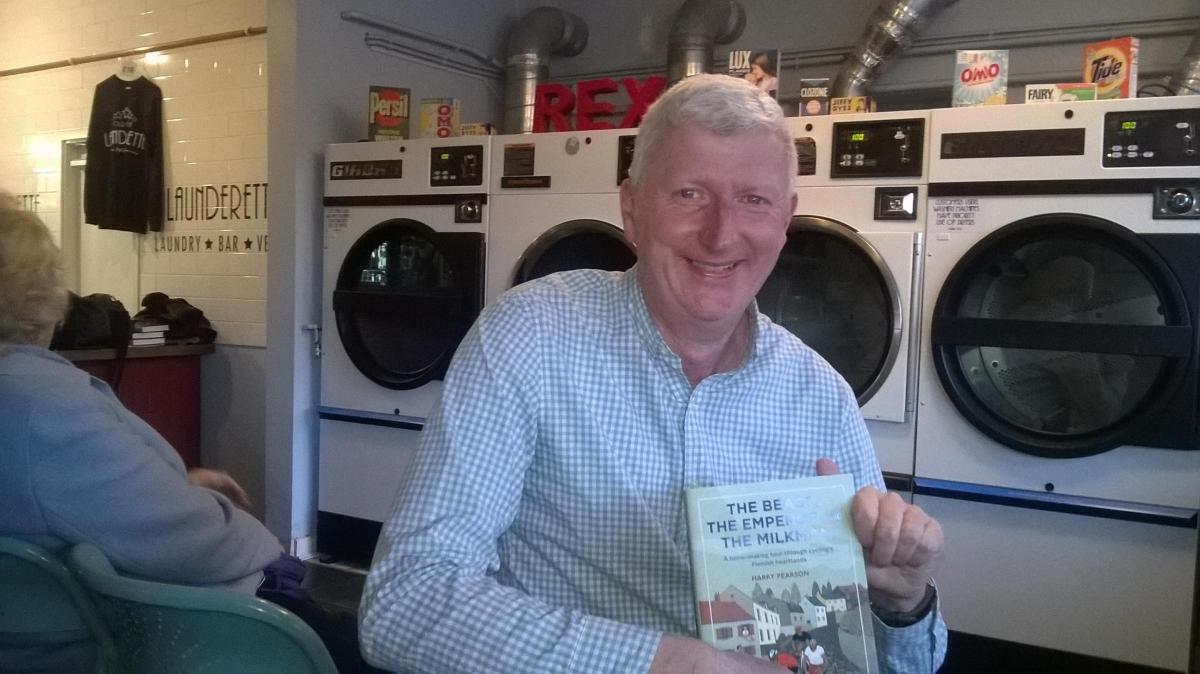

If the subject appears improbable – and it’s really not, Harry’s what’s apparently called a Belgophile – the venue for the book’s latest promotional evening is decidedly left-field.

It’s the Old Cinema Laundry at the top end of Gilesgate, in Durham, a place that really is what it says on side of the soap powder packet.

Opened in 1928 as the Crescent, the cinema became the 400-seat Rex in 1941, screened nightly until 1958 and after more adventures than a B-movie baddie was bought three years ago by Richard Turner and his wife Kathy.

There was a Rex cinema in Shildon, too. Had it been the Shildon Rex, there’d be a bloke coming round with ice lollies at the interval.

By day the Durham picture house is now a launderette – “fabulous” launderette, says the website – on many evenings an entertainment venue and bar.

Richard, who alternatively answers to Mr Wishy-Washy, is also a nurse, funeral celebrant and Air B&B operator. Kathy looks after the 9-5 laundry – “she does the hard work,” he admits – he oversees the entertainment.

He’d first encountered Harry, he tells the gathering, through his column in The Guardian. “It was good to have some intelligent football writing.”

Harry himself, born and raised in Great Ayton but now in Hexham, still travels by public transport and is fond of quoting lines attributed to Mrs Thatcher, that anyone who reaches 30 and is still travelling by bus must consider themselves a failure.

Apocryphal? It’s what comes of writing for The Guardian.

I’m in on the train, hoof the couple of miles up to Gilesgate, note that Durham seems rather less respectful of its bicycles than do the flying Flemings.

Several, chained to posts, are spread-eagled across the pavement – what health and safety call a trip hazard. The greater danger of an A-over-T episode, however, is from the silly busker playing a didgeridoo in North Road

The laundry can accommodate 55, seating of the uncomfortable sort that in former times might have been purchased for threepence, or two jam jars.

On top of the washing machines are boxes of Blue Daz (“family size, 1/8d”), of Rinso and Omo and of Lux Flakes, penny-ha’penny off. On the wall there’s an advert for the Hoover Keymatic.

Harry holds forth from in front of the washers – or maybe they’re the dryers – a tall and athletic figure, confident in the knowledge that no one’s going to pick Brand X.

It has to be said that £9 admission, including a half of beer or a coffee, seems a bit steep to hear a chap read from a book that he then hopes you’ll spend the neck end of £20 to buy but it’s wonderfully crafted, his learning worn lightly, like lycra.

As may never have been supposed of early adventures on two wheels, the guy simply can’t fall off.

NAMING famous Belgians, or even interesting ones, has almost become a parlour game. Harry could probably list 100 without engaging top gear, and every one of them a cyclist.

He loves the sport as much as he loves the country, spent two months there at the height of the racing season – a war correspondent might imagine himself embedded – completed the set with a fondness for Belgian beer, even at 13 euros a bottle.

Once he even found someone with little interest in cycle racing. “In Oudenaarde,” he wrote, “this was pretty much like a Catholic priest saying he didn’t much hold with all that Holy Trinity nonsense.”

The mild surprise at Durham is that he doesn’t once mention Tommy Simpson – what jobbing journalists call the local angle – though the book certainly does.

Simpson was born in Haswell, near Peterlee, youngest of six children to a miner who became the local workmen’s club steward before moving to find work in the Nottinghamshire coalfield.

The bairn was 12 when he got his first bike – second hand, shared – 26 when he became world road race champion, 27 when the first cyclist to be voted BBC Sports Personality of the Year and 29 when, in 1967, he died while flogging up Mont Ventoux in the Tour de France.

Amphetamines, then legal but unadvisable, were found in his pockets, amphetamines and alcohol in his blood. Whether leading from the front, as so often was the case, the man they called Major Tom was by no means alone in his aberration. Performance enhancing drugs were outlawed shortly afterwards.

Simpson had settled in Ghent. “He endeared himself to the Belgians,” writes Harry, “by playing on caricatures of Britishness like wearing a bowler hat and carrying a brolly, far from the realities of the England he’d grown up in.”

There’s a much-venerated statue at the spot where he fell, a bust in Ghent, a little museum in the Nottinghamshire village to which the family had moved and, finally in September 2017, a memorial stone in Haswell unveiled by Sir Bradley Wiggins after a fund raising initiative inspired by Major Tom’s family.

The inscription’s simple: “Olympic medallist, world champion and pioneer of British cycling.”

OUT in the wash, the Laundry’s gigs this next few weeks include everyone from the Unthanks, of whom I’ve heard, to Steve Ignorant of whom, rather appropriately, I haven’t.

Just that morning, however, Richard had confirmed perhaps his biggest name yet, the September 28 appearance of folk singer Julie Felix, born in the US but long in England.

We’d heard her back in 2005 at Frosterley village hall in Weardale, proceedings interrupted when she developed cramp in her toes. “I know I’m over the hill but I kinda like it on this side,” she said.

Frosterley sold out all 120 tickets at £6 a time. Durham offers 55 at £22. By the time she gets to make her debut in a laundry, Ms Felix will be 81.

INCORRIGIBLY sidetracking, Harry also touches upon shinty, a brutal sport last mentioned hereabouts in 2013 when Fergie Macdonald, 75, reached No 1 in the world iTunes charts with The Shinty Referee.

With his whistle and his stopwatch and his kilt above his knee

He’s the roughest, toughest man around, he’s the shinty referee.

Here’s the coincidence, though – the song was recorded in Glenfinnan, at the Old Laundry.

ONLY Harry Pearson could write about bike racing in Belgium and peddle a certain best seller in pretty pedestrian Blighty.

There are still plenty of reminders of his roots, though, right from page two when he explains that Flemings are northerners. “They like ale and chips and complaining. I’m a Yorkshireman so don’t write in.”

On page 43 he’s explaining how he gained some fluency in sporting French – football French – nu hazing at the pages of L’Equipe and hoping for some sort of osmosis.

“This policy had worked, more or less, though it had skewed my vocabulary to such an extent that, while capable of a relatively fluent discourse on Paul Gascoigne’s latest crisis, I couldn’t buy a train ticket without pointing and making chuff-chuff noises.”

By page 64 he’s dusting down the phrase “Get off and milk it” – known to generations of irreverent Co Durham urchins and clearly to those in Great Ayton, too – and sixty pages after that comparing Flemish ladies who spoke no English but gave him large amounts of cake with his great-aunts on Teesside.

“They were doughty northern matriarchs whose prime aim in life was to ply men with unhealthy foodstuffs until they keeled over and were finally out from under their feet so they could get some washing done.” They’d have felt wholly at home in Gilesgate.

*The Beast, the Emperor and the Milkman by Harry Pearson is published by Vloomsbury (£18.99).

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here