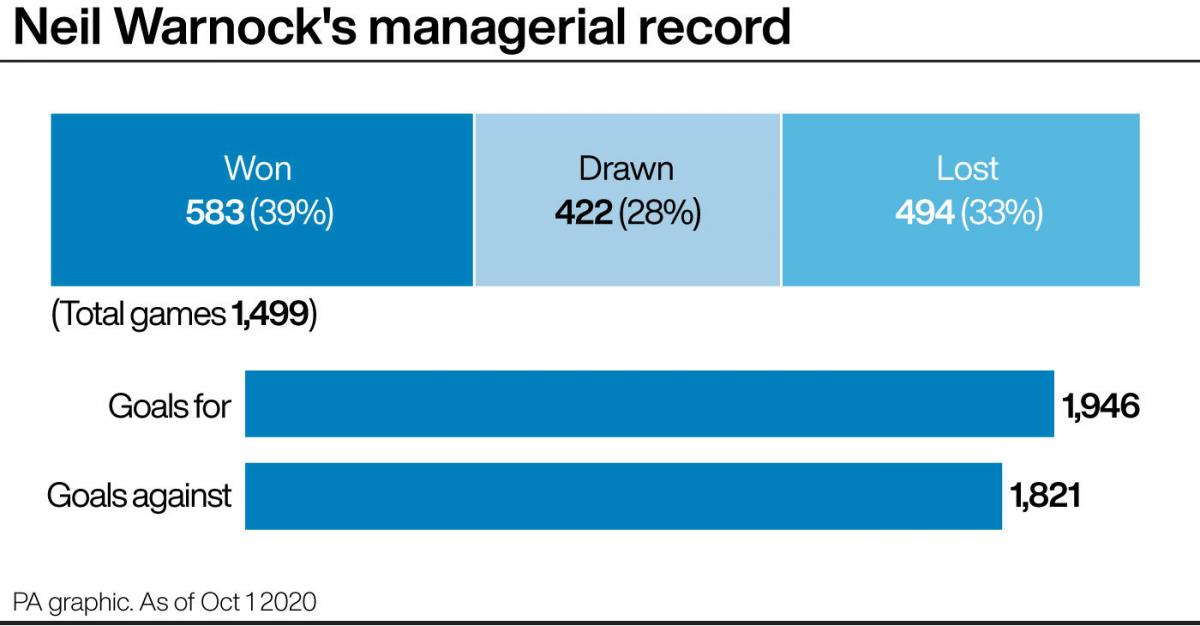

AT some point in the not-too-distant future, Neil Warnock will take off his tracksuit, forget about referees, and head off into the sunset as a former football boss. Let’s be honest, he’s threatened it plenty of times already. So, as he prepares to lead out Middlesbrough tomorrow afternoon in what will be a landmark 1,500th game in one of English football’s top four divisions, how would the 71-year-old like to be remembered when he does eventually decide to call it a day?

“Do you know what,” he said, thankfully back to full health after his recent bout of Covid. “I keep coming back to this one thing someone said to me when I was managing Cardiff. This bloke came up to me and said. “To be honest, we’ve never liked you. We didn’t want you here, but I’m glad you came’. That’s the sort of compliment I appreciate and enjoy.”

Warnock has always been the ‘marmite manager’, the figure opposition supporters love to hate. On plenty of occasions, he has been called things that could not be printed in a family newspaper. Often, to his face.

Yet, in the last few weeks, as news of his positive Covid test began to filter through, even the gruff South Yorkshireman has been forced to accept that perhaps he is more loved and respected than plenty would assume. From top-flight managers to fans on the street, people have rushed to wish Warnock all the best. If football really is a family, then perhaps he is the avuncular grandad whose stories from his rocking chair take on a new resonance as time rolls on.

Time. Warnock has spent four decades of it in football management, raging not so much against the dying of the light as at anyone and everyone who threatened to prevent his team from winning. He has witnessed so much that has changed markedly since the early 1980s, not least the advent of VAR and the change to the handball rules that has caused so much angst in the last few weeks, yet scratch below the surface, and the art of successful management remains largely unchanged.

At its core, it still involves taking a group of young players and trying to mould them into a successful team, while all the while also trying to improve each and every one of them as individuals. Warnock has spent 40 years pursuing those related ambitions, occasionally failing, often succeeding, but always wearing his heart on his sleeve.

“You are what you are,” he explains. “I used to have this discussion with Arsene Wenger. Arsene was so passionate inside, but he just never seemed show it like me. I mouthed off, although I suppose if I’d had his players, maybe I would have been able to keep quiet. I said, ‘It’s alright when you’ve got players like you’ve got – I’ve got to shout at mine’.

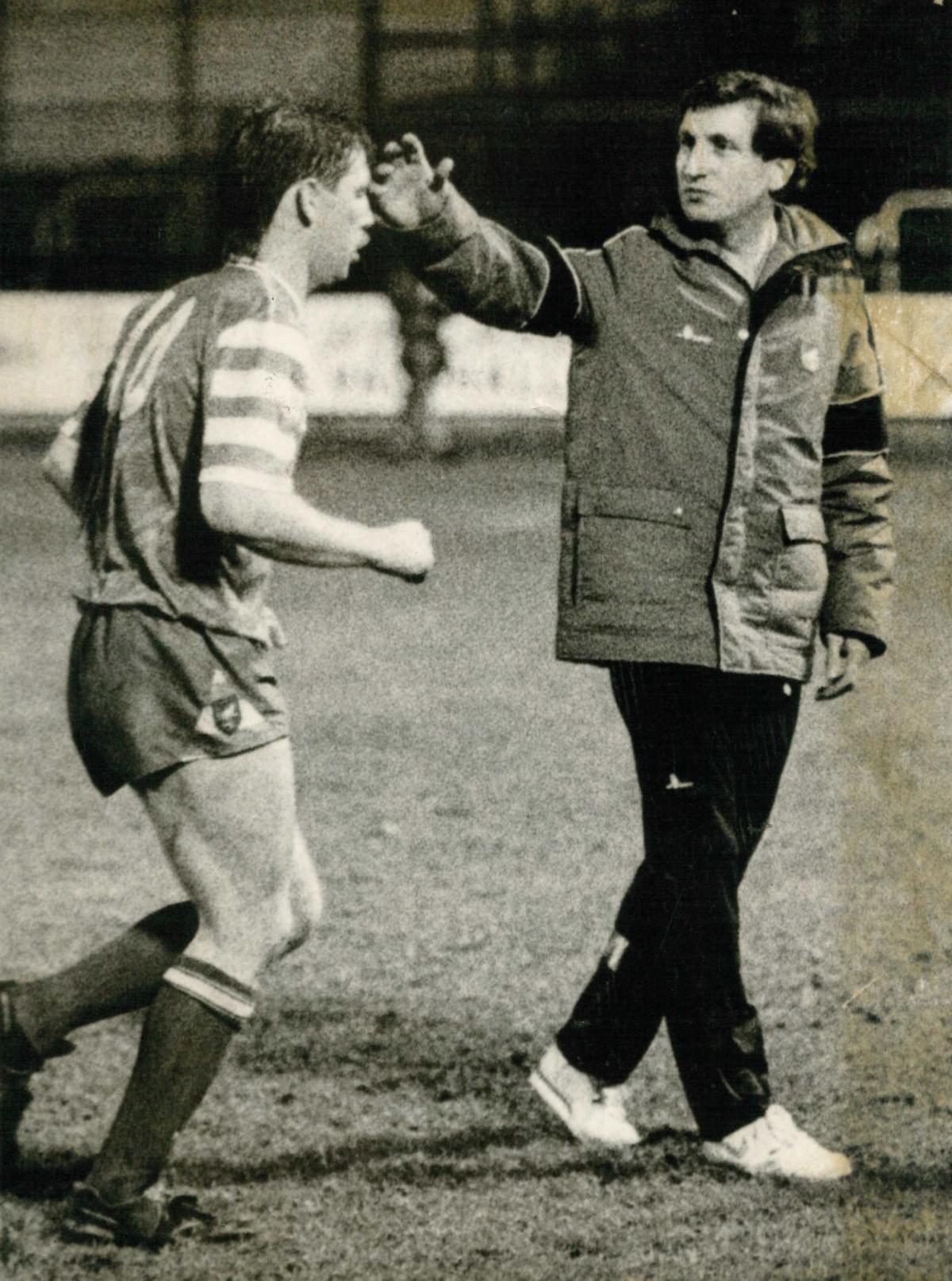

“You don’t lose that. When I managed my team at Hartlepool, the Under-13s at Seaton Carew, I managed the same way. I tried to make the players better than what they were, and I tried to give them a lift. I loved some of them, I gave one or two of them a rollocking, and that’s stayed the same.

“It’s the same whatever you do. Nothing’s changed now. The Championship seems to have been my number one league, and I’ve enjoyed it. It is a difficult league, but I do enjoy the rewards you get on a Saturday when you come out on the right end of a result and the fans are happy. It’s still a great feeling.”

Warnock has experienced the winning sensation on plenty of occasions over the course of his 1,500 matches, although it was not present on day one when he was in charge of Scarborough.

He had already cut his teeth in the non-league scene with Gainsborough Trinity and Burton Albion when he was appointed Scarborough boss in 1986, and along with his assistant, Paul Evans, he led the Yorkshire club into the Fourth Division as Conference champions.

His first game as a Football League manager pitted him against Wolves, and he can still remember the warm August afternoon as if it was yesterday.

“The first game? Easy. Wolves at Scarborough,” he said. “For some reason, they put the game on a Bank Holiday Saturday in August in Scarborough. Can you believe it? It was bedlam. I remember all the Wolves fans sleeping everywhere the night before. They were in every shop doorway, on the beaches, everywhere.

“I remember there was a fan who stood on the roof drunk and fell through it – he nearly killed himself, but fortunately he was alright. Steve Bull scored a couple, it was a 2-2 draw, and it was a great game.

“You look at where Scarborough are now, just set up again as Scarborough Athletic, and compare it to where Wolves are, in the top eight in the country. It just shows how close things are in football, and what a small line it is between success and failure.”

So, over the course of 1,500 games, what other matches stand out?

“There’s probably one a season, to be honest,” said Warnock. “The play-off finals were very special, I’ve been fortunate enough to win four out of four, and they stand out.

“To be honest, one of the most difficult games I remember, if not THE most difficult 45 minutes, was against Middlesbrough when I was boss of Notts County. It was the play-off semi-finals, and we came up to Middlesbrough and should have been two or three up, but it finished as a draw.

“I always used to be worried about the lad (Stuart) Ripley, he was the type I wanted, quick and direct, and in the second game, I’m thinking, ‘We shouldn’t be in this situation at all’. I felt sick in the second half, but the lad I signed from Barnet, Paul Harding, scored a header and we went to Wembley and won again.

“I probably remember those difficult times more than the euphoria to be honest. I’ve only felt sick a couple a times, but another one was when I was at Huddersfield and we were 3-0 up in a cup game. I knew if we could get to Wembley it would be so fantastic because they hadn’t been to Wembley since the 30s.

“I remember some people had booked coach trips before we’d even played the second leg, and I found out and went bananas. We conceded two goals early doors, my captain came off and I had to put a kid from university on, and then the ref played ten minutes injury-time at the end. Eventually, we won 3-2 and managed to get to Wembley.

“It’s games like that I remember, that were pivotal in my career. If they’d gone the other way, something else would have happened in management.”

Now, of course, he finds himself at Middlesbrough, his 18th club of a remarkably colourful and well-travelled career.

He remains as driven as passionate as ever, perhaps even more so in the wake of his recent illness, which provided a powerful reminder of just how privileged a position he finds himself in, doing something he loves.

He insists he has no real regrets, but he does have a message for those who have let him go along the way.

“Whenever I’ve left somewhere, I’ve always had the same message for people,” he said. “Owners, players, fans, whatever. I say, be careful what you wish for. You won’t get a better manager than me...”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here