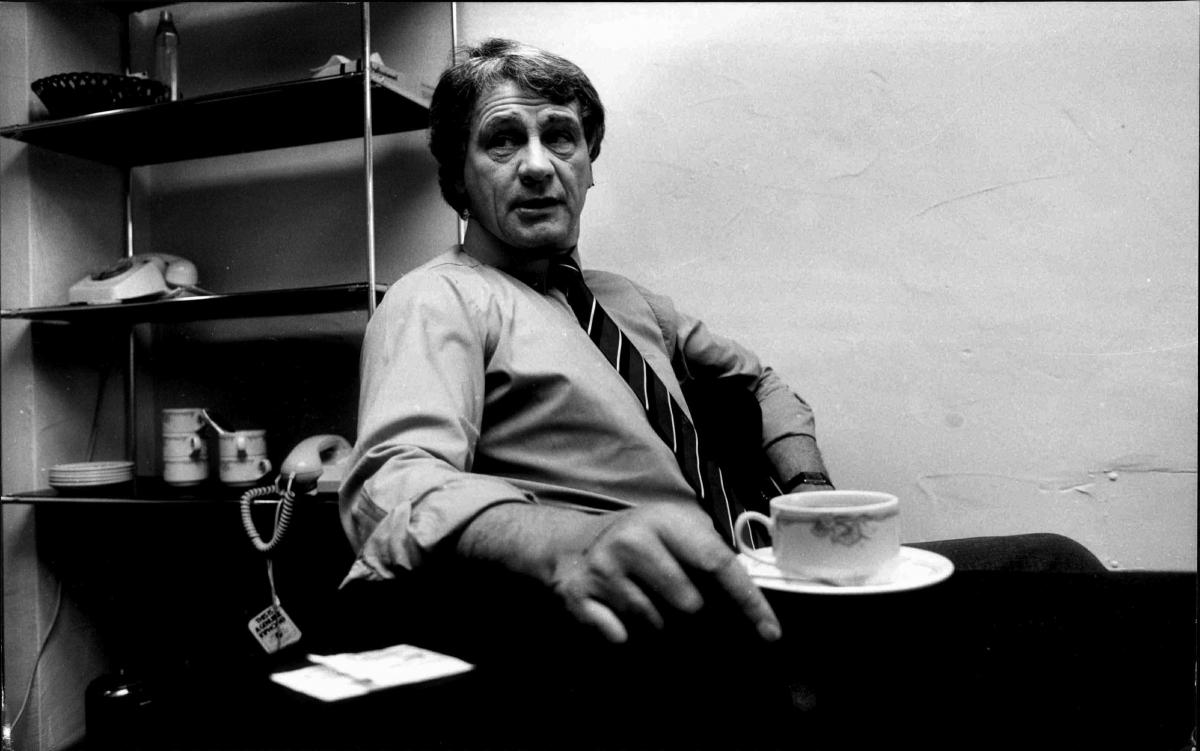

On September 24, deCoubertin Books will publish a new biography of Sir Bobby Robson.

Written by Bob Harris, who was Robson's friend, confidante and collaborator for more than 30 years, "Bobby Robson: The Ultimate Patriot" charts Robson's rise from humble beginnings in County Durham to become one of the most successful and popular figures in the footballing world.

Here, in two exclusive extracts in The Northern Echo, Harris examines Robson's early years, both on and off the pitch.

Like father like son as Bobby learned early lessons from his dad

Bobby’s coalminer father Philip was no penny pincher, far from it, but he was a good accountant and from him Bobby learned the value of a pound.

The Robsons were of Methodist stock and few of the family indulged in strong drink or tobacco. Bobby enjoyed the occasional cigar and the odd glass of wine with meals, but was was never a compulsive drinker like so many British footballers of his age.

One of the problems of the age was footwear, which was expensive to buy and expensive to repair. Kids often dragged their satchels to school in the rain with holes in their soles, letting in the wet and leaving their socks and feet damp all day. Luckily for the Robsons, Philip was an accomplished self-taught cobbler and was able to turn his hand to repairs when necessary. Given the amount of football played by the boys in the fields and in the backyard, it was a good job.

Because Philip spent little or nothing on his own social life, there were always coppers to spare for a family holiday, another rarity in the neighbourhood. A few pints after a shift down the mine soon bled the money away for most families. The Robson family would go away every summer, first of all to the local resort of Whitley Bay and then, later, when there was a little more cash coming in from the boys and from Philip’s regular promotions, the glamour of Blackpool, the Las Vegas of the North of England.

The financial acumen he learned from his father was to carry forward in Bobby’s life and a skill that became particularly useful in his days as a manager. He hated waste of any sort. He treated every penny spent as if it were his own, particularly at Ipswich Town where the money was tight. At Portman Road each signing and every wage increase, including his own, was carefully weighed up. As a result, Ipswich finished in the black every year he was in charge apart from the summer they invested in building a new stand at Portman Road, money well spent and supervised by their diligent manager.

Bobby was happy to pass on his frugality to others and when Ipswich were playing Derby County at the old Baseball Ground he insisted on the Ipswich board joining him on a visit to the local mine at Swadlincote, where his brother Tom was working. It is funny just to think of the upper-class Cobbold brothers John and Patrick being dressed up in coveralls, wearing hard hats and carrying miners’ lamps – it’s likely they couldn’t wait to get back to their bottle of Sancerre and let their manager get on with the accounting and the managing.

Why Bobby Robson turned his back on the superstars of Newcastle United

Bobby’s performances as an underage player were attracting attention from the scouts who watched games at all levels in droves looking for the next Jackie Milburn. Wor Jackie came from down the road in nearby Ashington, the same village that produced Jack and Bobby Charlton. The slightly built Robson looked a good bet to follow in his footsteps.

When he was 15 he was invited by both Middlesbrough and Southampton for trials and did enough to tempt both clubs into making offers. Saints followed it up, but in the end he chose the more local club in Boro and signed on schoolboy terms.

During this period Newcastle lost a lot of local, promising youngsters who saw a difficult path through to the first team, and history is littered with top players who quit the North-East to find their fame elsewhere, places where there were more opportunities to make the grade in first team football. Robson, the Charlton brothers and the talented Howard Kendall are just a few of the names who left the area before they had made a professional appearance in the game.

He was far from satisfied with the attention he received from Middlesbrough, with invitations to travel to Ayresome Park for training and, more importantly, for games, all too rare and when they came back to him on his 17th birthday to sign professional terms, he stunned them by telling them he wasn’t interested.

With Philip insisting that he served his apprenticeship as an electrician, he was a grown man by the time it needed a decision and the choices on offer were wide and varied. Although he admitted he would have crawled on his hands and knees the 17 miles to Newcastle United, he made the decision that they were so full of the superstars of their time that opportunities would have been few and far between for him to make an impression.

Southampton were back, Middlesbrough were desperate, as were the other local rivals Sunderland. Also in the frame were Lincoln, York, Blackpool, Huddersfield and Fulham. All had something to offer this budding young man who was determined to become a successful professional.

Everyone, especially Philip, naturally assumed that St James’ Park would be his destination, but Bobby learned another footballing lesson that was to stand him in good stead when he went into management. He elected to travel south to London and Fulham because their manager Bill Dodgin had taken the trouble to drive north himself to talk to Bobby and Philip personally, not leaving it to a local scout.

Bobby met Bill for the first time when he finished his shift at the colliery and found the Gateshead-born manager, who had first tracked him when he was at Southampton, sitting outside the house with his mam and dad. Neither were keen to see their youngest move away from home, but Bill had a persuasive tongue and he convinced Bobby that he would have a much better chance of making it at Craven Cottage where they encouraged young players and brought them into the first team, whereas at Newcastle he would always be subservient to the big stars brought in for big money.

Bobby was convinced but his dad wasn’t, and it was only when Bill agreed that the youngster should carry on his electrical apprenticeship in the south that the deal was struck. Philip wanted his son to have something to fall back on if he failed to earn a living as a footballer and it meant that Bobby travelled to the banks of the Thames as a part-time professional, training in the evening with the other part-timers, instead of in the morning when the seniors went about their business.

- Bobby Robson: The Ultimate Patriot by Bob Harris is published by deCoubertin Books on September 24, priced £20. The book also includes a foreword by Gary Lineker.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel