Durham-born Richard Smith’s story is an extraordinary one. Released by Sunderland as a teenager, his dream of a career in professional football was shattered, but through the assistance of the Professional Footballers’ Association, he is studying medicine at America’s world-renowned Harvard University. Now he wants to help footballers recover from their injuries as an orthopaedic surgeon.

THERE is a photograph of Richard Smith at Sunderland’s Stadium of Light which acquires further poignancy each year.

The image shows him next to Jordan Henderson and a fresh-faced goalkeeper by the name of Jordan Pickford. Since their time together at Sunderland’s Academy a decade ago, though, their careers have taken distinctly different paths.

While Henderson, Liverpool’s admirable captain, and Pickford, Everton’s goalkeeper, are now both established England internationals, Durham-born Smith was added to the list of the thousands of players who wash through the system every year, their dreams of a professional career broken.

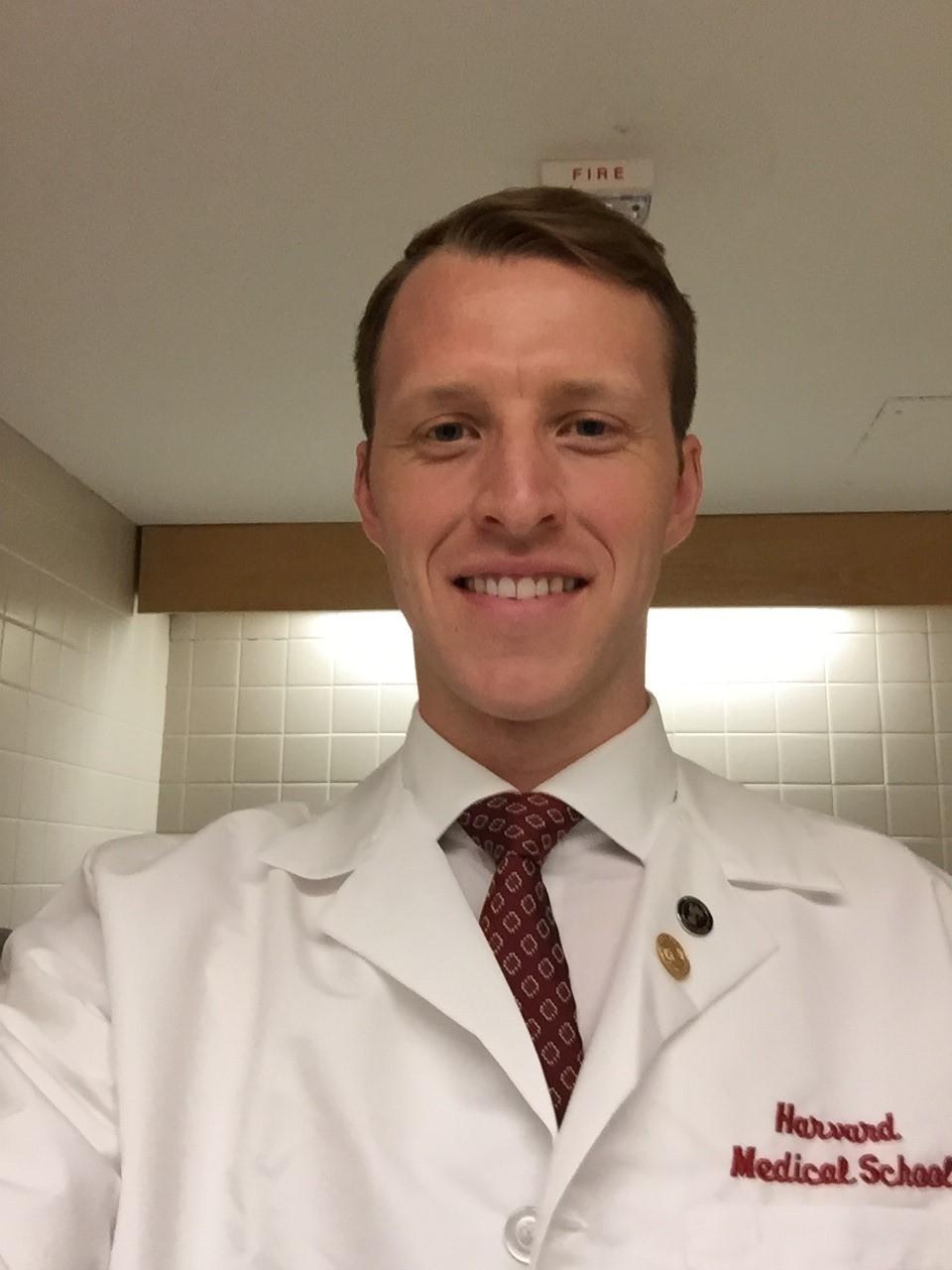

Instead of become a professional footballer, ten years on he is at Harvard Medical School in America training to become a doctor.

“I think that’s why the picture is there, to show that there is life after football, and that success is not necessarily defined by playing in the Premier League or as a professional footballer,” he said.

And sometimes, the starkly unequal nature of the game means these boys can be parachuted from the rarefied environment of swish, multi-million pounds youth complexes into non-league football.

As a young footballer, everyone is selling the dream to them.

“To be told at 18 that the thing you love most in life is not there anymore is devastating,” said Smith, who attended Framwellgate School, before joining the youth ranks at Sunderland, who helped win the Premier Youth League Championship in 2006-07.

“When somebody tells you that you’re not good enough then that is a very difficult thing to hear.

“I felt crushed and the dream evaporated in front of my eyes.”

He adds: “Having been relatively successful on the pitch and in the classroom, it was the first time that I’d experienced failure. I did ask myself whether I’d wasted two years of my life for nothing.

“It was a very dark time – the most difficult experience of my life.

“A large percentage of Academy players never make it, so that’s why the Professional Footballers’ Association do play such a crucial role helping these players go through difficult and uncertain times.”

After leaving Sunderland Smith, now 29, dropped into non-league and was in the Durham City team which won the Northern League first division in 2007-08.

Ten years on and, at the time of this interview, he is at the end of a punishing 12-hour weekend shift at an accident and emergency department.

He is at a hospital in Boston, the capital of Massachusetts, as part of his practical training.

If all goes to plan he will graduate as a doctor in two years, with his eventual goal to operate as an orthopaedic surgeon.

Often he is physically and mentally exhausted, but the adrenalin drives him on, just like it did when he chased the football dream.

“Working in a medical team is a bit like football because it is very team orientated, the senior consultants and junior doctors work collaboratively like a manager and his squad.

“Things can get tough, you are at the sharp end of life and there are times when it does get very emotionally challenging.

“Helping somebody to get better is the greatest of rewards, but when a patient doesn’t make it, then that can be devastating, and it encroaches into your own personal life.

“You do face death sometimes and that’s hard.”

Smith, though, says he will always be very grateful to the PFA for their help and guidance.

He added: “The academic costs in America for medical school are very high, so the PFA, in particular Pat Lally, have been incredibly generous in supporting me in so many ways.

“It probably would not have been possible for me to attend Harvard Medical School without their generous and unstinting support.

“Certainly, if I came home to England, I would consider becoming an active member of the PFA union. It is a fabulous institution, doing so much for so many and they are often under-appreciated.”

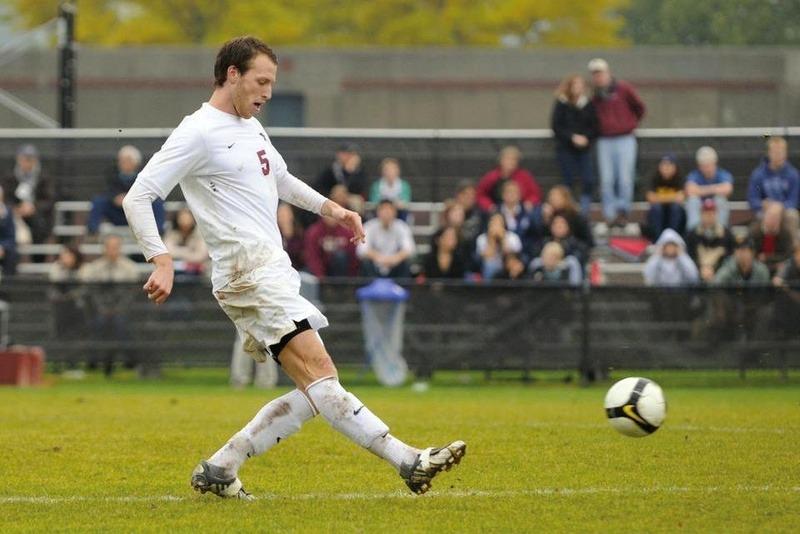

Smith admits his rejection by Sunderland did make him mentally stronger for the next chapter in his life. And it was his former youth coach at Sunderland, Kevin Ball, that encouraged him to make that giant step to a new life in America, where he has combined a successful stint in college football with his medical studies.

“I probably knew deep down that I wasn’t going to make it at Sunderland,” he admits. “But even if I didn’t play professionally, I didn’t want to bounce around in non-league.

“It did harden me. I came out of that experience more resilient and better prepared for life.”

Richard already had a PHD in Musculoskeletal Injuries at Oxford University under his belt before moving to America.

He added: “My time at Sunderland exposed me to many different types of bone injuries. I closely experienced and witnessed many of them. “Orthopaedics provides an opportunity to help people get back to doing what they love.

“That can be a football injury or just walking a few steps in the garden with their grandchildren again, so they too can continue doing what they love doing.

“The possibility of having such an effect on a person’s life is very rewarding.”

When he talks about Henderson and Pickford there is a genuine pride in his what they have achieved.

“I’ve seen hundreds of players, but I’ve never known two footballers who had more of a raw passion for football,” he adds. “They were diligent, committed, fiercely so, and they took it to another level really.

“Jordan Henderson is a great lad and loves the game more than anybody and he deserves the success he is enjoying with Liverpool.

“What I’m doing, studying to be a doctor, is the most challenging thing that I’ve ever done.

“But I’ve still got the bug, you know. I’d love the opportunity to play professional football when I graduate.

“I don’t think that I could ever lose that boyhood dream.”

He says: “On the flip side, I hope that my experience can help demonstrate that there can be life after football.

“I cannot thank Sunderland and the Professional Footballers’ Association enough for all their support.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here