TRAVEL to The Turnstile, the estate that was built on the patch of land where Ayresome Park once stood, and you will find plenty of reminders of Middlesbrough’s much-missed former home. There is a street named The Holgate in memory of the raucous home end, and a bronze ball to mark where the centre-circle once stood.

Look to the floor though, and you will be led to the spot of one of the most remarkable moments in footballing history. Wedged between the lawns and gardens, a bronze cast of an imprint of a football boot, created by the sculptor Neville Gabie, marks the exact point, close to the penalty spot at the Holgate End, where North Korea’s Pak Do-ik struck the shot that beat Italy.

Tuesday marks the 50th anniversary of the moment, and even now, with the roll call of those who witnessed the feat at first hand fast diminishing, it has lost none of its ability to shock. There have been plenty of footballing upsets in the five decades since England hosted the World Cup finals in 1966, but few have matched the North Koreans’ group-stage win for sheer incredulity.

“The fall of the Roman Empire had nothing on this,” wrote The Northern Echo’s Jack Fletcher on the back page of the following day’s newspaper, with the sense of surprise accentuated by the extent to which the North Koreans were embraced by a Teesside public that quickly fell in love with them.

Fourteen years ago, the seven remaining members of the North Korean squad returned to Middlesbrough for an emotional visit that saw Pak Do-ik, who was an army corporal when he first travelled to England and then a gymnastics instructor later in his life, return to the spot that came to define him.

“It was the day I learnt football is not all about winning," said Pak. “When I scored that goal, the people of Middlesbrough took us to their hearts. I learnt that playing football can improve diplomatic relations and promote peace.”

That 2002 visit, with Teessiders falling over themselves to greet the North Korean players, underlined the enduring affection in which the players from north of the 38th parallel are still regarded. Yet for quite a while, it looked as though they would not be allowed to travel to England in the first place.

The Korean War had ended just 13 years before the start of the 1966 tournament – a formal peace treaty with South Korea was never signed – and with Britain refusing to recognise the communist North Korean state, the Foreign Office had initially argued against allowing North Korean players to compete on English soil.

FIFA intervened, and after flying into London, the North Koreans travelled to the North-East by train, with passengers reportedly bemused as they sang patriotic songs throughout their journey.

They stayed at the St George Hotel, next to what is now Durham Tees Valley Airport, and assigned a Teesside-based journalist, Bernard Gent, to be their press officer.

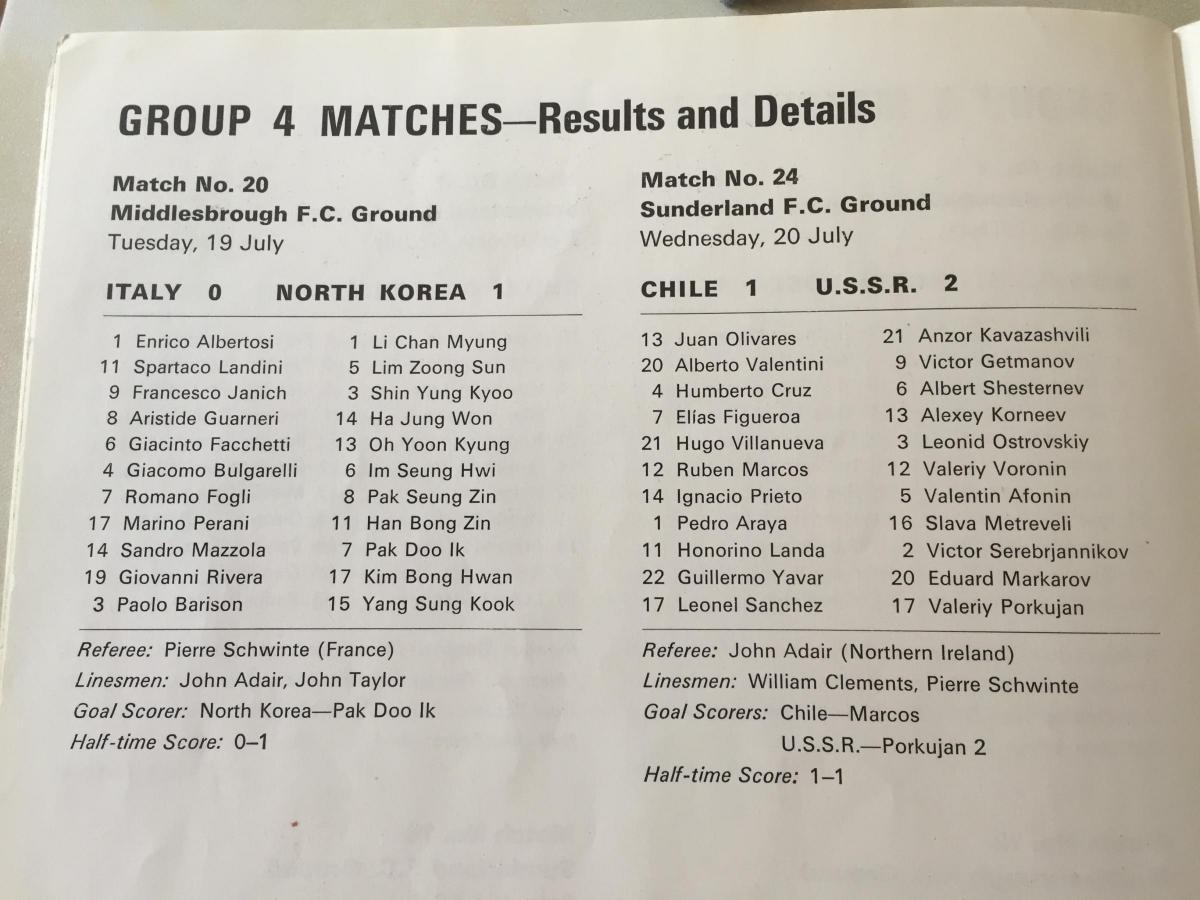

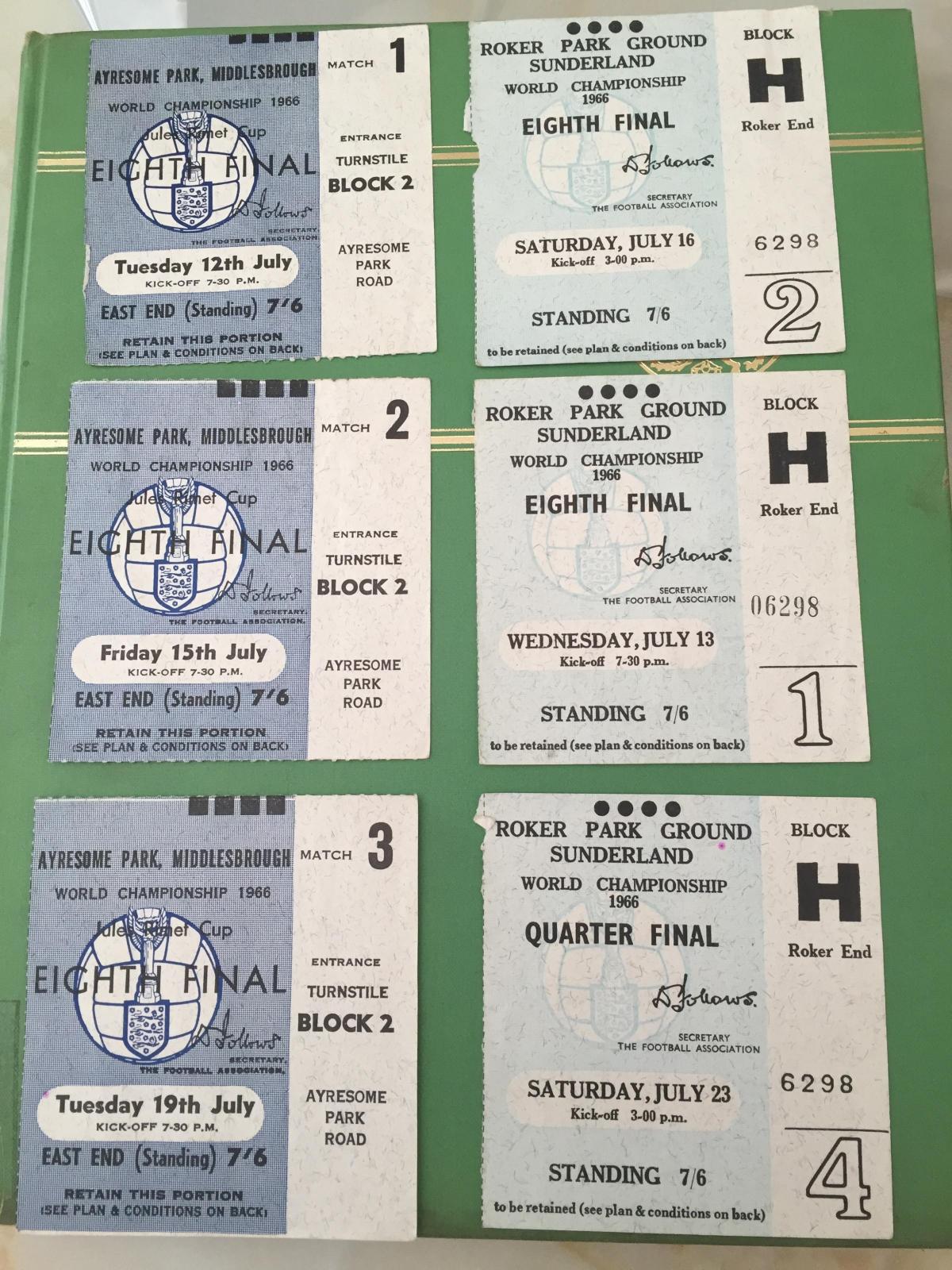

They played all three of their group matches at Ayresome Park, and while the first resulted in a resounding 3-0 defeat to the USSR, the second, a 1-1 draw with Chile, meant they went into their final group game with a chance of qualifying for the knockout rounds.

They had won over an initially sceptical Teesside public, partly because of their underdog status, partly because of their adventurous, committed playing style, and partly no doubt because they played in red, just like Middlesbrough.

On the morning of the Italy game, The Northern Echo reported: “If willing a team to win means anything – and I have no doubt it does in the Oriental mind – then Italy will have to watch out at Ayresome Park tonight.

“For the one certain thing about the last of the World Cup games on Teesside is that North Korea will enjoy vocal encouragement just as lusty, and perhaps almost as fanatical, as if they were performing before their own Asiatic brethren somewhere on the top side of the 38th parallel.

“One of my abiding soccer memories will be the mighty roar which greeted the Koreans’ equalising goal two minutes from the end of their match against Chile last Friday night. It must have rattled the test tubes at ICI Wilton. It could scarcely have been more enthusiastic if Boro’ had been winning promotion to the First Division.”

A crowd of 18,727 turned out to watch the game against Italy, and while there was a healthy contingent of Italians present, the vast majority of neutrals were firmly behind North Korea.

Italy suffered a body blow when the influential Giacomo Bulgarelli was stretchered off with torn knee ligaments in the 35th minute – with no substitutes allowed in those days, they were forced to play for an hour or so with ten men – and just six minutes later, North Korea were ahead.

Pak Do-ik controlled a pass on the right-hand side of the penalty area, burst forward five yards or so, and angled a shot across goalkeeper Enrico Albertosi and into the right-hand corner of the net. It might be apocryphal, but it is alleged that the crowd reaction resulted in the strip lighting in the press box going off.

Lifelong Boro fan John Flynn reminisced about his favourite match at the time of the North Koreans’ visit in 2002. “I was at the game and remember a tremendous atmosphere,” he said. “The Middlesbrough fans got behind the Koreans and were delighted when they scored. I remember some ice-cream sellers at the match, who were Italian, and they threw down their cornets at the final whistle in disgust.”

North Korea’s qualification for the quarter-finals still hung in the balance, but was confirmed when the USSR beat Chile in the final Group Four game at Roker Park.

Italy, who had been certain of qualification, had booked their quarter-final accommodation in a Jesuit seminary, and when they no longer required it, the North Koreans were able to take it on instead. Brought up in a strictly secular Communist society, North Korea’s players had never seen Christian iconography, and a number spoke of their terror at seeing statues of a man with nails in him. A handful even claimed they could not get to sleep.

It is estimated that around 3,000 Teessiders travelled to Goodison Park to support North Korea against Portugal, and an even greater shock than the one they had secured against Italy looked on the cards when goals from Pak Seung-zin, Li Dong-woon and Yang Sung-kook fired the minnows into a 3-0 lead.

Portugal stirred though, inspired by the peerless Eusebio who scored four goals, and eventually ran out 5-3 winners. They would go on to lose to England in the semi-finals.

The North Koreans returned home, and for more than three-and-a-half decades, that was the end of their story. In the late 1990s, however, a film maker, Daniel Gordon, spoke to the North Korean authorities requesting permission to shoot a BBC documentary about the events of 1966.

After a four-year wait, he and his producer, Nick Bonner, finally received a visa to travel to Pyongyang, and their film, ‘The Game Of Their Lives’, was premiered in Sheffield in 2002.

“The Korean authorities were quite curious and pleased we wanted to do something fairly neutral about their country,” said Gordon. “And the players were really delighted because they thought they had been forgotten about by the rest of the world.

“The first thing one of them said to me was, ‘Is the mayor of Middlesbrough still alive?’ I knew there was a strong bond, but didn’t think it would have lasted that long.”

Gordon and Bonner were both invited to attend special screenings of their film in Pyongyang, and one evening, while in the company of some of the Stalinist state’s ruling elite, they suggested it might be nice for the surviving members of the squad to travel to England.

To their surprise, their invitiation was accepted, and while the North Korean players visited London to see the Houses of Parliament, a trip to Middlesbrough was always going to form part of their trip.

“Their only experience of the West is Middlesbrough, and it has made a massive impression on them,” said Gordon, in an interview with The Northern Echo. “Time has not been too kind to the team. Many of them have subsequently died. Life is hard in North Korea and, according to the US, the average male life expectancy is only 51.

“They came back to Britain because many of them wanted to see Middlesbrough again before they died – not in a morbid way, but to remember the joy they had there.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here