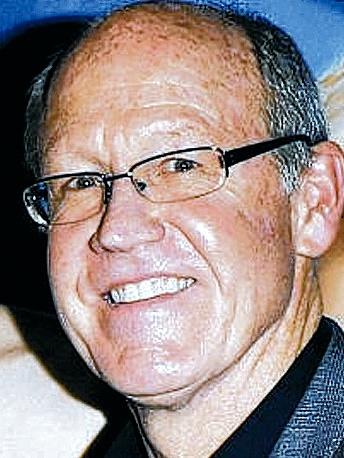

The man who created the Little Mermaid, Aladdin and the Beast has been called one of the greatest Disney animators ever. Glen Keane tells Steve Pratt he embraces computer animation, but remains an artist at heart.

NO ONE embodies the meeting of hand-drawn and computer animation as Glen Keane does. With 35 years service at Disney, his career straddles both the old and the new.

Oscar-winner John Lasseter, who holds the creative reigns at Disney/Pixar, calls him “one of the greatest Disney animators ever” – a reference to Keane’s creation of such characters as little mermaid Ariel, the uglier half of Beauty and The Beast, Pocahontas, Aladdin and a dreadlocked Tarzan. He’s taking the legacy of the original Disney animators into the computer age, while continuing to hand-draw the “old-fashioned” way.

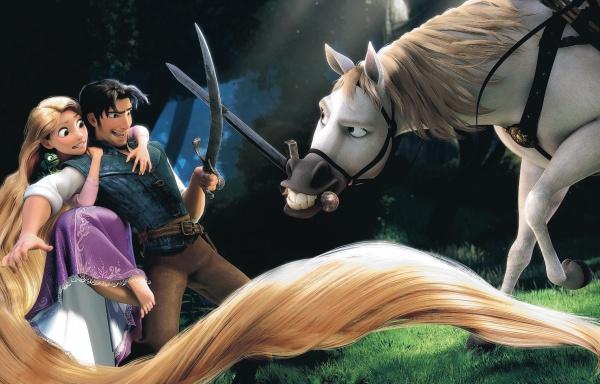

Tangled, the studio’s take on the fairy story Rapunzel, and Disney’s 50th animated feature, is truly a blend of hand-drawn and computer art, thanks to animation supervisor and executive producer Keane.

He originally presented the idea to then- Disney boss Michael Eisner in 2002, as a traditional animation. “I showed him my drawings and he said, ‘yes, I love it, let’s do this movie’, but he wanted to do it on the computer,” recalls Keane, visiting this country for the London premiere of Tangled.

“I pointed to the drawings and said, ‘Michael, do you like them?’ and he said ‘I love them’. But I said, ‘you can’t do this in the computer’. And he said that’s the point – I want you to find a way to take what you love in hand-drawn and put it into computer animation.

“Now, he may not have been giving me that challenge for artistic goals, but I thought it was an honest challenge that I couldn’t say no to.”

As the son of Bil Keane, creator and cartoonist of nationally-syndicated US comic strip The Family Circus, he was exposed to art from an early age, with his father encouraging him to learn how to draw, not just cartoons, but anatomy and real life.

He intended to be an editorial cartoonist, but his portfolio was sent to the wrong place in college and he ended up at the school of film graphics – animation – by accident.

Despite his love of drawing, he’s always loved computer animation. After he and Lasseter saw an early version of Tron in the Eighties, they investigated animating backgrounds by computer and characters being hand-drawn.

Keane thought that what he loved in handdrawing wasn’t possible in the computer. Now it is, with programmers responding to his demands.

For example, symmetry – the computer creates perfect people, more like robots. “Typically, you design one side of the face, duplicate it to the other and you’re done,” he says. “But you don’t meet two people the same, every side of a face is different. So we started to design Rapunzel asymmetrically.

“For example, the teeth were sculpted, making them unique. Perhaps one eye is a little higher than the other. It was really important that computer animators’ tools had the same kind of flexibility as hand-drawn animators.”

The results amazed even him. “I never would have believed it possible. I can see every animator in the animation of the character. It’s not a mask, it’s not a puppet. They’re animating that face, putting themselves in there.”

For six months, he thought Tangled wasn’t going to work. After a year, only 40 per cent of the animation was complete. “And it was incredible, this collective learning took place and in the last two months the most amazing scenes – 60 per cent of the movie – were animated.”

Not just the look, but the movement of humans needed to improve. “Every time a computer generated (CG) character moved across the screen, it seemed like they were floating and I always felt they were like puppets.”

Everybody told him to try animating on a computer. “So, for one day, I did and it was painful, so difficult. He worked to find ways to make computer characters more human, such as a slight expansion of the chest and raising of the shoulders when someone breathes in.

“You think this isn’t a CG digital figure, there’s lungs inside and a warmth to the skin. We really looked for those kind of tangible things.

“I felt we really challenged the animators to have something so specific they wanted to achieve in their acting and wouldn’t accept anything less.”

HE was able to instil a new enthusiasm in the animators, many new to the studio, by reminding them of the Disney heritage.

“They were breathing Disney air as part of this system of Disney animators,” he says.

He related the principles of animation taught by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, two of the legendary Nine Old Men of Disney’s early animators.

“I was constantly remembering the notes from Ollie. He would tell me things, I would write them down and pin them on my desk.

He’d say don’t animate what the character’s doing, animate what the character’s thinking.”

A digital tablet enabled him to show Tangled animators what he meant by drawing over a frame of animation which was used by computer animators to improve the scene. The process fits into Keane’s philosophy of embracing the computer and putting your personal touch on it.

And next? “I think I’m going to do something with a pencil. I really like drawing. I feel the traditional Disney animation needs to grow, to move in a new direction.

“Maybe by using the computer, it can be liberated and you can celebrate hand-drawing.

I’ve always loved the computer, but there’s something so personal in drawing.”

As he’s shown in Rapunzel, it is possible to have the best of both worlds.

* Tangled (PG) is now showing in cinemas.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here