Second of a six-part reprise of 46 years in journalism, Mike Amos recalls how he was nearly locked up for stealing ten shillings from the gas meter.

BACK in the Sixties, drugs were something you bought at Timothy White and Taylor’s. though they may better have been known as Beecham’s Powders.

Probably it helped explain why the crime rate was relatively low and why most of the recorded transgressions, the deadbeats and the drunk and dizzies, was really pretty small beer.

In three-and-a-half years on the south Durham patch, there was only one murder, a broken-hearted affair up at Stanhope where the chap handed himself in next day.

Armed robbery was almost unheard of, big league burglary rarely a problem until the night that they pinched Mrs Shafto’s Ming Buddha from Whitworth Hall, outside Spennymoor.

Rosa Edwina Marguerite Duncombe Shafto – funny how you remember these things – was a descendant of Bonny Bobbie. The Ming was worth an estimated £10,000, an awful lot of oriental treasure..

The case was given to Det Chief Insp Nobby Clark – he who memorably observed that, like Cockfield Band, he was just buggering about – and to Det Insp Charlie Organ, his able deputy.

It took them months, but finally they arrested a professional burglar in Leeds, returned the Ming whence it had come.

That same night it was stolen again, a forlorn Charlie Organ encountered outside the court next morning. His reaction wasn’t quite Buddha, but something pretty similar, nonetheless.

THE magistrates’ courts were different, too, not the matrixled, monosyllabic sentencing supermarkets that they have become today. They were human.

Bishop on Monday mornings was frequently enlivened by the appearance of George Henry Wilson, 21 Lane Head, Copley – something else committed to memory. George Henry was the town drunk, usually thrown off the last bus home and given B&B in the penitential suite.

Local industrialist George Cosgrove, nice chap, was bench chairman when George Henry, cap quite literally in hand, once more trudged up sobriety’s steps and into dry dock.

George Henry sighed; George sighed. “You again, George Henry?”

“Aye, Mr Cosgrove. It’s these young pollisses.”

The banter continued for some time. Finally the chairman resumed magisterial authority. “Why now, George Henry. We’ve had a bit crack on but what are we going to dee with yer.”

“Dee?” echoed George Henry, indignantly.

“You’re not ganna dee nowt are yer?”

The chairman sighed once more.

“No,” he said, “bugger off back home and don’t let me see you here again.”

THE late Ronnie Heslop, aka Rubberbones, may be as familiar to regular readers as he was to denizens of County Durham’s courts, the soubriquet earned after he became the first man to escape from Durham Jail.

It was 1961. Rubberbones, then in Ushaw Moor but originally from Page Bank – the village of the Great Flood – had used a teaspooon painstakingly to remove the grill from his cell floor, somehow squeezed into the empty and unlocked cell below and was off into the night.

He was on the run for several weeks, swam the swollen Wear to escape pursuing police dogs, was eagerly absorbed into Page Bank society (and into its long roof voids, too).

Though there were one or two further skirmishes with the law, he became a decent citizen and a likeable bloke. Many years later, however, John McVicar – an altogether harder and less agreeable nut – claimed in his autobiography that he, McVicar, had been first over the Durham wall.

I went to see Ronnie, the poor lad duly shocked at the unarmed robbery on his claim to fame. We wanted a photograph of him on Page Bank bridge; Ronnie wanted a fiver.

In all these years, and all thanks to John McVicar, it remains a lone foray into what the professionals call cheque book journalism.

IN 1969 I joined the Echo, chief reporter in the York office where we had four reporters, a photographer and a billet in the city centre.

All that was wrong with York was that it wasn’t in County Durham.

Two crimes come immediately to mind, the first at Elmfield Terrace where the tattooed toerag in the flat above removed all the shillings from my gas meter and tried to implicate me. “Your fingerprints are all over it,” claimed one of George Henry’s young pollisses. It seemed a little superfluous to suggest that, yes, well they might be.

The second, altogether more serious, occurred at 15 Rosemary Lane, just off Walmgate.

In those days, the night duty reporter made calls every couple of hours to police, fire and ambulance in the absurdly optimistic belief that they might actually tell us what was going on.

Then one night, all four of us enjoying a beer in the Three Cranes, they did. It was 10.15pm, 30 minutes to first edition deadline. A body, said the police, had been found in unexplained circumstances.

We knew the shorthand, grabbed a taxi to Rosemary Lane, between the four of us sorted out a pretty good story.

The investigation was led by the redoubtable Det Chief Supt Arthur Harrison, a fabled operator, but even he felt finally obliged to seek outside assistance, thus establishing a first and a last. It was the last time in England that a provincial police force called in Scotland Yard to help with a non-terrorist killing – and the first (and last) time that I’d yelled excitedly down the telephone to someone in Darlington that they’d really better hold the front page.

MARK Johns was murdered in February 1983, though it was five months before anyone realised.

In 1949 he’d become the world’s first full-time television critic, on the Express, later worked in public relations and as campaign director for Keep Britain Tidy. In 1973, citing exhaustion from the rat race, he bought the Bowes Moor Hotel on the A66, near the Durham/Cumbria border.

“Dick Whittington in reverse gear,” the John North column supposed.

As Mark’s guest, I stayed there several times. Clearly he desperately missed the journalistic society from which supposedly he had fled, usually he talked – or, effectively, delivered a monologue – into the small hours.

Bowes Moor seemed to have an awful lot of cuddies without hind legs.

The dream was dying, patrons few.

He disappeared that February owing £50,000 to Durham County Council for the mortgage and much else besides.

When his car was found abandoned near Hull docks, everyone – not least Jo, his 21-years younger wife – simply assumed he’d fled to Europe.

That July, however, two youths – former Bowes Moor employees – were arrested in Darlington for a minor burglary. “While we’re here,” they said, “we might as well tell you about the murder”.

Directed to a shallow grave, police immediately began digging on the nearby moor. The youths had blasted Mark from the staircase as he walked below.

The hotel has had several subsequent owners, none of whom seems to have lasted long. When we passed a few weeks ago it was again empty, sorrowful and for sale.

Blag and baggage

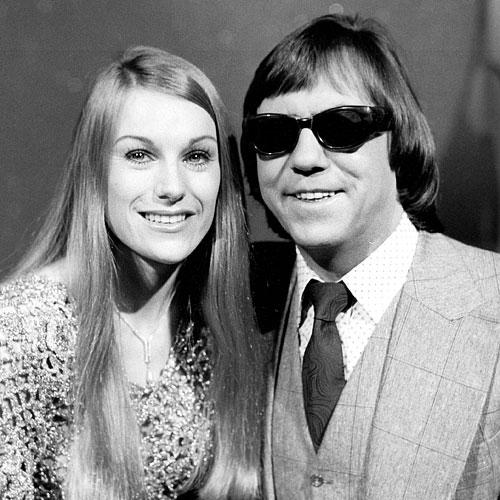

IT’S shortly after 11pm, a clear Spring evening in 1973. Last bus habitually missed, I’m walking home towards Shildon when an elderly Thames van pulls alongside and a chap in dark glasses leans out to ask directions to the GR Club.

Since I’m headed that way, I’m invited to jump in.

The club owner’s already outside, looking (shall we say) a little anxious. The duo are the cabaret, the place is full – it didn’t take much – and they’re running late.

The turn, it transpires, are Peters and Lee.

Welcome Home. their first hit single, has reached No 1 in the charts a few days previously.

The club owner is (of course) George Reynolds.

It wouldn’t be a crime and punishment reprise without George Reynolds.

Lennie Peters, who’s blind – and whose nephew is Charlie Watts, the Rolling Stones drummer – politely suggests that, since they’ve kept their side of the bargain despite hitting the high spots since the booking was agreed, they might have a small increase on the fee.

“I booked you when you were no one,” says George, contract in hand. Peters and Lee, top of the pops, play Shildon for £12.50.

WE’RE old friends, both Shildon lads more or less, cheek by non-judgmental jowl in the corridors of Bishop magistrates court and in sundry other courts of justice.

Once I was his best man. Not the time he married at a posh castle in the Highlands, the time before that. The time he married at Bishop Auckland register office.

For George, blowing safes (and associated activities) was often little more than a game of cops and robbers – like the time he blagged a quarry explosives store at Bolam, above West Auckland.

The police rang round the newspapers, asked us to print an appeal for witnesses, anyone who’d seen anything suspicious. Many had indeed, the police switchboard illuminating like Blackpool on an autumn afternoon.

Not only had they spotted a big blue van parked on a nearby road, but the big blue van had both a large dolphin and a Shildon telephone number, 2779, on the side.

George owned the Dolphin Coffee Bar, named after his beloved alsatian, had a telephone number approximately between 2778 and 2780.

The polliss paid a visit to his split-level bungalow.

George claimed that the van must have been stolen. Asked what it was again doing outside the house, he replied that the thieves must kindly have returned it.

Memory on this one may be errant, but I’m pretty sure he got off.

BACK in the Seventies there was a charge of being a reputed thief loitering with intent.

May still be. They used it when nothing else seemed likely to stick. Tony Hawkins was a reputed thief, all right.

Tony was a Willington lad, registered trade mark burgling Co-ops through the front door.

One day he jumped bail, had it away on his toes as old Arthur used to say in Minder.

George rang our house a few days later, around midnight. Tony wanted to give himself up, he said, but not before telling his side of the story. We were to meet George outside the King Willie in ten minutes.

Hawkins, hiding beneath a proggy mat in the back of the same blue van, poked his head from beneath it in the manner of Kenneth Williams accosting Tony Hancock in the Test Pilot.

“Hello,” he said.

Undetected by whichever member of Shildon constabulary had drawn the back shift short straw we headed off road to Brussleton Folly, long gone, where Tony insisted that it wasn’t all at the Co-op after all.

At 3am it was time to hand himself in to Bishop Auckland police station, the only problem that the van was stuck in the mud. Tony and I pushed, back wheels spinning, becoming ever more filthy.

George sat in the driver’s seat like Lord Muck, though the analogy may be inappropriate. Tony may have been confessing, but he certainly wasn’t coming clean.

We arrived at the police station an hour later.

The duty constable glanced up and at once put down his Beano. “We’ve been expecting you, Tony,” he said. The rest of us went back to bed.

THEN George became chairman of Darlington FC – saved them from oblivion, it should be recalled – built them a handsome stadium but, like Icharus, flew too close to the sun.

Though ever-garrulous, he no longer waxed so lyrical.

The guy, further to pillage Greek mythology, has two Achilles heels. The first is women, and by no means alone in that, the second that he surrounded himself with yes men when he desperately needed someone to say No. Or at least Whoa.

In the inky trade it’s possible to become acquainted with a great many well-known people, thus you speak as you find. George, to me, has always been generous, honest, straightforward, loyal and (not least) jolly good copy.

A law unto himself, maybe, but we are friends yet.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here