From child star to actress fiancee of Britain’s most famous tennis player, Darlington girl Mary Lawson crammed an awful lot into her short life.

MARY LAWSON was the railwayman’s daughter who became engaged to the greatest sporting star of her generation. She was born in a humble terraced street and died in the arms of her fabulously wealthy husband beneath a German air-raid.

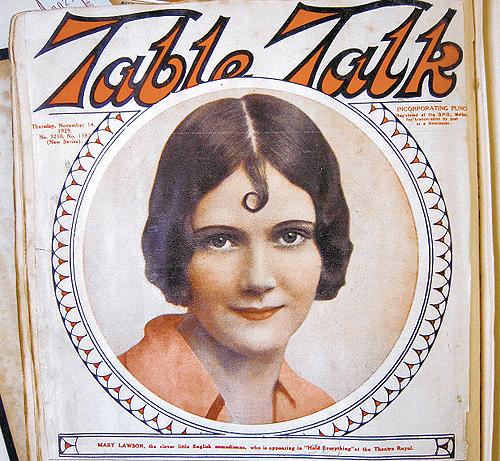

She was the child star with a little kiss curl. She first wowed audiences in the Scala cinema, in Darlington, but went on to win hearts in Her Majesty’s Theatre, in Sydney, Australia.

One stage magazine described her as a “petite, retrousee-nosed, earnest North of England girl”.

Others described her as Darlington’s Gracie Fields.

She starred in 14 films, and her life reads like a film script.

We laid out a synopsis a couple of weeks ago. Now, with the help of two scrapbooks compiled by her father and kept by her cousins, we can fill in some of the plotlines.

She was born on August 20, 1910, at 58 Pease Street, off Yarm Road, the third of three children. Her father, Tommy, was a North Eastern Railway cranedriver; her mother died when she was three and her elder sister, Dora, chaperoned her around the world.

Mary’s career began when she was five, singing God Bless My Soldier Daddy to injured servicemen who were billeted in the Feethams mansion in the Leadyard.

She later said: “When only six-year-old, I sang to the inmates of a Durham asylum. Evidently I pleased the audience, for one inmate gave me a huge bundle of newspapers and, wrapped up inside, was a new sixpence.

That represented my first stage earnings.”

Her regular booking was at the Scala – now a bingo hall off Eldon Street in Darlington’s North End – where she sang and danced while the projectionist changed the film reels. They called her “the Scala Pet”, or “Little Mary Lawson” – a nickname she never grew out of as she didn’t make it to five feet.

By 11, and still at Dodmire School, she had a burgeoning reputation in south Durham. The scrapbook, for instance, has a programme for the Middleton-in-Teesdale Agricultural Society Concert of March 1921, where she sang I Want a Daddy Who Will Rock Me To Sleep.

A year later, she made her professional debut in a musical comedy called Sunshine Sally, which opened at the Theatre Royal in Northgate, Darlington. Its star was Miss Dot Stephens, a well-known actress who was making her comeback, having lost a foot and all her toes in a railway accident.

Called “the pluckiest girl on the stage”, Miss Stephens amazed the audience by dancing and cycling on her wooden appendages.

But Little Mary Lawson stole the show with her rendition of Golden Curls.

After the Theatre Royal, Sunshine Sally toured the UK provinces.

Mary recalled: “It seemed to me almost impossible to believe that there were so many terrible places in the world as the Midlands towns where our company appeared.”

It meant an end to 12-yearold Mary’s full-time education – one of Dora’s chaperoning duties was to get her into a new school each week as the show moved around.

In 1925, the scrapbook reveals that she had made it to the capital for The London Revue at the Lyceum Theatre. Top of the bill was an American movie star called Pearl White, and Mary – “a diminutive dancer” – was paired with an up-andcoming Max Wall, who was two years her senior.

Together, they performed Nipper and Nippy, and ’Arry and ’Arriet.

Then Mary went into provincial panto, from where she was selected for the summer season at Frintonon- Sea, Essex, in The Lido Follies. It doesn’t sound glamorous, but the show was put together by Archie Pitt – married to Gracie Fields – who doubled Mary’s wages to £4 a week.

That summer – 1928 – the Daily Mail launched its Search for a Seaside Stage Star. Gracie was either impressed by the 17-year-old or wanted publicity for her husband’s show and so sent a telegram to the Mail’s theatrical correspondent William Pollock advising him to have a look at Mary.

When he labelled her “the most promising girl I have seen”, it was as if Simon Cowell had pronounced her the winner of The X Factor.

Within weeks, she was snapped up by a London impresario who put her in cabaret at the Mayfair Hotel, in Berkeley Square. Within months she was catapulted into the West End as a replacement for a US leading lady, Zelma O’Neal, who had unexpectedly been called home.

When Mary’s father, Tommy, heard, he took time off from driving his crane and travelled through Friday night from Darlington “to see me make my debut in the heart of theatredom”.

She was in the musical Good News at the Carlton Theatre and her big number was The Varsity Drag.

“She was so successful that at the end, the whole of the cast, principals and chorus, crowded round and cheered the 17-year-old girl who had won her spurs,” said the Daily Express.

Good News toured the provinces, including two weeks at Newcastle Empire Theatre. The papers wrote it up as a homecoming, and in a brilliant piece of PR, every journalist called on Mary’s humble home in Pease Street where they all found her doing the cleaning.

“In her handbag was a contract guaranteeing her an income of nearly £3,000-ayear, but a visitor might have mistaken her for any of the 50 shilling-a-week typists and shopgirls living in the same street,” wrote one.

“Attired in a plain skirt and a thoroughly sensible jumper – with sleeves rolled up for the fray – she dashed about energetically and washed and scrubbed and dusted”.

THE lucrative contract sailed Mary and Dora off to Australia, via New York, for a year. She returned a superstar. She walked back in to the West End, received endorsements – “Miss Mary Lawson finds it essential to start the day on Shredded Wheat” – and moved into movies.

In May 1934, she was engaged to a cameraman, but then the tennis star Fred Perry visited her on the set of Falling In Love. They fell in love and that August became engaged.

It was a sensation – particularly as the engagement only lasted eight months as Perry – the last British male to win Wimbledon – furthered his career in the US.

Said Mary: “Publicity has killed our romance. I am sick and tired of the ridiculous rumours and of being rung up time after time about some story or other.”

She soon found a new love.

She appeared in films with stars as famous as Stanley Holloway, Vivien Leigh and Bud Flanagan, but only had eyes for the producer of The Toilers of the Sea, Francis WLC Beaumont. The dramatic film, in which a steamer crashes onto Channel Islands rocks and the hero grapples with an 8ft octopus, was shot in Sark where Beaumont’s mother was the Seigneur – the feudal ruler.

In November 1937, he asked for a divorce from his wife on the grounds of his adultery with Miss Mary Lawson, and the following year they married. Only Mary’s father and sister witnessed the ceremony as Beaumont’s mother, Dame Sibyl, was far from happy with the match.

Tragically, it didn’t last long. On May 4, 1941, the couple were with friends in Liverpool. For the eighth consecutive night, the city was struck by an air raid. As the sirens wailed, Dora and their friends retreated to the shelter while they stayed in their room.

As the Echo reported on its front page, when the house was struck by a bomb their friends survived, whereas they died.

Mary was only 31.

Her star had faded a little as none of her films were successes, but she was still sought after on the stage.

As the curtain dropped sadly, poor Dora was left alone. It is believed her soldier-boy had perished in the First World War, allowing her to sacrifice her life to her sister who died in the Second.

“I seem to have nothing to live for now,” she told the Echo. “We were so much together.”

Dora lived near Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire and returned to Darlington in the early Nineties to spend her last year in a nursing home in Abbey Road. She regarded the town as home, and had regularly visited her brother, Francis, and his wife, Edith, and their three children; Mary, Mike and Barbara.

Mary now lives in Westonsuper- Mare, while Mike and Barbara remain in Darlington.

They have their famous aunt’s scrapbooks, the locally-made dressing table that sailed with her to New York and Australia, a trinket box given to her by Fred Perry and one faded memory.

“When I was about two or three,” says Mike, 71, who is two years older than Barbara, “I remember her visiting in a sports car and we sat in the dickie seat at the back, but that’s it.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here