For two weeks in August 1984, Easington was under a virtual state of siege as the first miner defied the strike and went back to work.

Marjorie McIntyre talks to former NUM lodge secretary Alan Cummings about the dispute which changed his home village forever.

LIKE Margaret Thatcher, Alan Cummings is the child of a greengrocer, but there the similarity ends. While Baroness Thatcher followed her father’s example and went into politics, Alan refused to heed his dad’s advice and instead went down the pit.

Born and bred in Easington Colliery, Alan was just 15 when, in 1963, he began work at the village pit. “My dad tried to persuade me to stay on at school, but for as long as I could remember I wanted to be a miner and it is a decision I have never regretted,’’ he says.

The articulate pitman rose through the ranks at his National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) lodge and by 1976 – already a veteran of two major skirmishes with the National Coal Board in 1972 and 1974 – he had been elected to the powerful post of lodge secretary at Easington Colliery.

It was a position which placed him at the heart of the coming dispute, as miners in Yorkshire became the first to walk out over the pit closure programme announced by Ian MacGregor in March 1984.

On March 9, with the axe beginning to fall and fearful for the industry’s very existence, the NUM invoked its obscure Rule 41, which allowed mining districts to make their own individual decisions to strike.

Nottingham miners voted to stay at work, but at Easington more than 1,800 members of the NUM decided to stand up and fight for the future of their colliery and became the first pit in the Durham coalfield to down tools on March 12.

At Easington, picket rotas were drawn up, miners’ wives organised a free cafe and, with the rest of the Durham coalfield joining the strike, both sides dug in for the battle ahead.

Communities united behind their pitmen and life in the strike-hit villages took on a normality of its own, a normality which was to last through the spring and the early hot summer of 1984.

In August, however, amid angry scenes, Ken Seed, a member of Cosa (Colliery Officials and Staff Association) took the decision to return to work at Wearmouth colliery. In a costly publicity campaign, strikers were offered cash inducements and free transport to return to work. The strike had remained solid at Easington until suddenly, in mid-August, pickets watched on as a specially-hired bus completed several runs through the east Durham mining villages ready to pick up any miner wanting to return to work. Empty runs continued on a daily basis until August 20 – the fateful morning when one of the pickets cried “there’s someone on board”.

It was Paul Wilkinson, a 28-year-old power loader who had transferred to Easington Colliery from Kelloe a few months earlier. For several days, the solitary strike-breaker was brought to the pithead only to be turned away at the colliery gates by the sheer force of picket numbers.

But at about 8.30am on August 24, when most of the Easington men were on picket line duty elsewhere, police road blocks sealed the two entrances to the village, an armoured convoy of police vans sped into the village and Mr Wilkinson was escorted into the colliery through its pithead baths entrance.

Alan sent out a call to his members who returned to Easington via small country lanes, to be met, for the first time in history, by riot police on the streets of a North-East village.

Fearing what lay ahead, Alan and lodge chairman Bill Stobbs, went into the colliery manager’s office warning of the consequences and pleading for Mr Wilkinson to be taken out of the pit.

The request was refused and when Alan passed the news on to the now swelling numbers of pitmen, he recalls: “All hell broke loose between the pickets and the hundreds of police officers in riot gear. A lot of men got into the colliery yard and, unfortunately, there was damage done and a number of cars were overturned.

‘I did my best to make sure none of my lads got hurt, but things were nasty for about 45 minutes.

One lad got severely beaten and he was taken to the manager’s office where he was arrested, but charges were later dropped and compensation paid to the injured man.”

At about 3pm, Easington’s MP, the late Jack Dormand, also attempted to intervene in a bid to quell the rising anger in the village. By then, five policemen and three miners had been injured, four pickets had been arrested and half a dozen cars overturned.

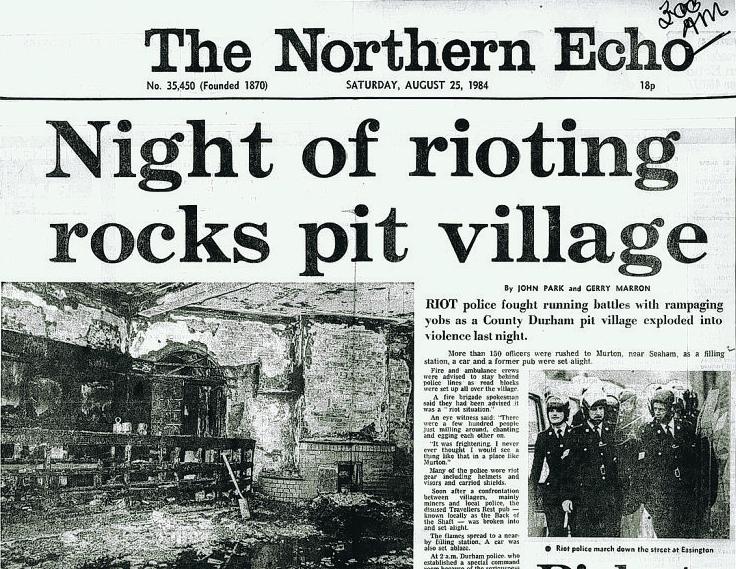

That night, the frustration and violence spilled over again in nearby Murton, where a full-scale riot broke out. During sporadic skirmishes throughout the night, the empty Traveller’s Rest pub was broken into and set on fire, the flames spreading to a neighbouring petrol station, as 150 police officers took on pickets, who overturned cars in the street and set them on fire.

In Horden, a 200-strong crowd vented its anger at a number of targets, including the windows of a taxi firm which carried working miners.

The mood had changed. The following day another huge police presence was on duty in Easington, many of them officers from far-flung counties such as Northamptonshire and Gwent, who would remain for the rest of the strike.

“The spectacle of police in riot gear lining the streets day after day was shocking for those living in the village.

A flash point came every morning as Wilkinson was brought into work in a heavily armoured bus ominously driven by a man in a ski mask,’’ says Alan.

“We became a village under siege; children and old folk were terrified by the lines of police, wearing riot helmets and with shields and batons drawn, and for the law-abiding people of Easington all trust in the police was gone.’’ In what became near wartime conditions Alan and his pickets used CB radios to signal messages of where police convoys were as they escorted Mr Wilkinson, and later his father, to work each day.

Still living in the colliery house he bought with his late, beloved wife, Lynne, and where they reared their son, John, Alan still harbours deep bitterness against the “scabs” who he blames entirely for the miners’ ultimate defeat.

“We were not fighting for money, but for our jobs and the future of our communities, and though there was only a handful of them, the scabs gave succour and confidence to the Tories who would never have beaten us if we had stuck together.”

By February the following year, with the trickle back to work continuing, Alan knew they were staring defeat in the face and prepared for the bitter prospect of leading the proud pitmen back to work. “We had led them out and it was our responsibility to lead them back.’’ The pitmen’s fears for their industry were to prove prophetic and on May 7, 1993, Easington was the last pit in the Durham coalfield to close.

“The irony is that in the two months before we were shut down Easington Colliery had made a £3m profit and had at least 20 million known tonnes of coal in its seams,” says Alan.

With recently-announced new moves to restart the coal industry in the region, he reflects wistfully: “We were right to try to fight for our pits, and we will never forget the sacrifice those thousands of men and their families made, nor the legacy left by Mrs Thatcher’s government of decimated communities, devastated economies and the deteriorating health of the beleaguered people of the Durham coalfield.”

Though the industry has been wiped out, Alan, who is president of the village’s colliery band, a school governor and an advocate for former pitmen, still fights on for the community he still believes in.

“Despite the closure of our pit, this is still called Easington Colliery and it will, I can assure you, remain so.’’

■ TOMORROW: Tory MP Michael Fallon on the lessons he learned during the strike.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here