YOU’VE heard of 15 minutes of fame? Jim Elliott had his, almost set your watch by it, at Highbury on April 8, 1972. Then he headed to Kings Cross, a one-way ticket back to Bishop Auckland.

The boy they called Flash – inherited from his dad, a Powderhall sprinter – was a 16-year-old apprentice with Wolves, brought on as a 76th minute sub in their 2-1 defeat against Arsenal.

His ability was both immense and well recognised, half the big clubs in the land sedulously seeking his signature. “There were fellers coming every night. Every time I got home from school there was someone different,” he recalled when we chatted at his mum’s house in Bishop in 1991.

After Highbury, he went back to playing for Witton Park Rose and Crown. “These days it would be called an attitude problem,” he said, “but I just wanted to be at home with my mates.”

Jim, whose funeral was held yesterday – he was just 63 – had recalled that thrown-to-the-Wolves afternoon back in 1991.

“Bill McGarry was the Wolves manager, 38,000 in. I was terrified, I thought I’d only gone for the ride out. Arsenal had two stewards on every door and half of them thought I was a kid trying to get in for nowt. Every one of them stopped me.

“I was a young lad from a little place like Witton Park in strange lodgings in a big town. Derek Dougan was an absolute gentleman but a lot of the other players just ignored you. People say I was stupid to pack it in, but they’ve never had to try it.

“I had this reputation for drinking and being a bit of a lad, but it wasn’t really fair. Maybe the smoking had something to do with it.”

It wasn’t that Wolves didn’t want him back, just that he preferred Bishop, the boys and (let’s be honest) the beer. “Fair enough I smoked when I was 15, fair enough I liked a game of cards at the Aclet but that was just a couple of bottles. I wasn’t anything like as bad as people made me out to be.”

Nor did he reflect his nickname. Nothing at all Flash, or fake, about Jimmy Elliott.

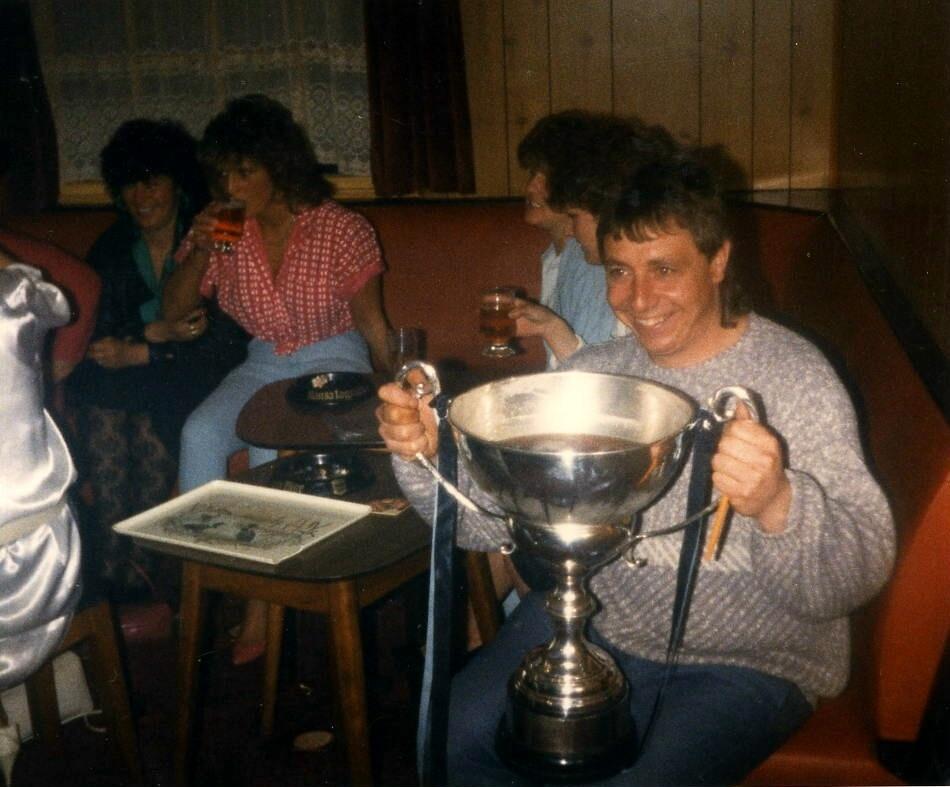

He was a Witton Park lad, helped the village school to the county small schools cup, joined the triumphant parade around the village. “It was a sensation and quite right, too” headmaster Roy Thomas once recalled.

Later he played for Bishop Auckland Boys alongside Evenwood lad Barry Bolton, who went on to play for Chelsea and for Ajax.

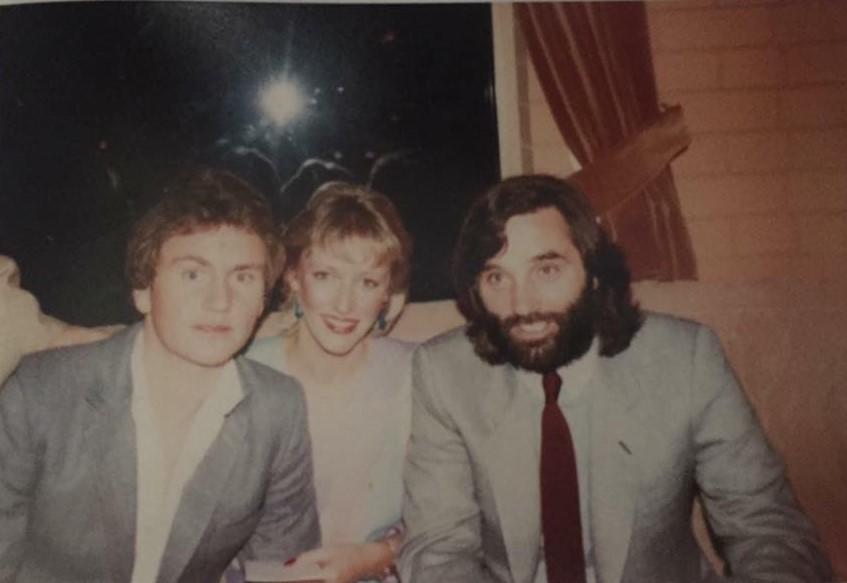

Witton Park historian Dale Daniel, who provides images of the young Jim, also sends a photograph of Bolton with a yet-better remembered footballer. Whether the young lady is one of Barry’s or of Besty’s is unknown.

At 15 years and 265 days, Jim had become the youngest player to represent the amateurs of Bishop Auckland in the Northern League, scoring in a 4-1 win at Penrith and finding a quid in his boot.

“That £1 got me into the town hall dance that night, three shillings I think, so maybe we had a couple of drinks,” he said.

Over subsequent years we’d usually meet on a late night No 1 bus, Jim returning from a game of dominoes – a dab hand, they reckon – and the amount in his debut boot steadily increasing. Inflation, presumably.

After deciding that he didn’t want to leave home, he scored three times in a couple of games for Newcastle United’s Ns side, was told he’d be informed of the next, never got the call.

Thereafter he was content to play for pub teams in the Bishop Auckland area, even that terminated at 30 when he suffered a serious back injury at work.

The consultant told him he might never walk again. “Aa could have told thoo that,” said Jim.

Friend and former team mate Mike Rudd recalls a player way ahead of his time. “He was a joy to watch, someone with genuine skill who was doing things fifty years ago that television pundits now drool over. He was also a genuinely funny guy, at the forefront of everything.”

Jim, who never married, lived alone at Leeholme, near Bishop Auckland. He was found dead at home – “a terrible tragedy,” says Mike Rudd, “and a terrible waste of talent.”

Last week’s piece on former England footballer Dave Thomas – now registered blind and a Bishop Auckland schoolboy a few years before Jim Elliott – stirred particular memories for John Coe in Willington.

John was centre half, “Ticer” Thomas right half in the district team in 1963.”The Crook and Bishop Auckland teams had just been amalgamated and there’d been a trial match between the two sides,” John recalls. “I still don’t know which way Dave went. I hardly even saw him.”

The goalkeeper, another Willington lad, was big Martin Burleigh, later of Newcastle United, Darlington, Hartlepool and one or two more and last heard of as a painter and decorator in Ferryhill.

Is he still painting the town red (and various other colours)? Anyone know what happened to him? Martin’s now 68, Dave Thomas is 69 today.

To Willington last Saturday, perchance, where the programme recalled former Sunderland manager Alan Durban’s improbable appointment as the Northern League club’s team boss in 1984-85.

“If the appointment had surprised the football world,” the programme adds, “the next appointment left it stunned and shaken.”

That was the flamboyant Malcolm Allison, previously Middlesbrough’s manager, known worldwide but banned from all football at the time after failing to pay a £250 FA fine imposed after comments to the referee following a Boro game.

Like Billy Bunter, Big Mal insisted that the cheque was in the post, but thought it wiser to maintain a watching brief until it actually arrived.

Like Durban, he stayed for ten matches of which half were won. After showing Willington, Durban became manager of second division Cardiff City. Allison became national coach in Kuwait.

Among several readers to commiserate over Somerset’s all-too familiar second place in the county cricket championship – also noted in last week’s column – John Raw in Bishop Auckland offers a story from former Somerset and England quickie Fred Rumsey’s latest book.

Fred was the county players’ union rep, offered to intervene when Aussie all-rounder Bill Alley was declined a contract for the following season.

Alley declined, explaining that his eyesight was beginning to go, so he was taking up umpiring instead. He stood it, and made the test panel, for many years thereafter.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here