On and off for many a year, it has been the column’s irregular custom to convene a gathering of the FA Cup Escape Final Committee (and Scotch Pie Fest), its direction northwards, its intention obvious.

Roads high and low pointed last Saturday towards Dumfries, home for the final five of his 37 colourful years to Rabbie Burns and much more recently to Allan Ball, a Hetton-le-Hole colliery electrician who became a Scottish football legend.

Dumfries is the base of Queen of the South, the dear old Doonhamers – facing Raith Rovers a week ago in the Scottish Championship play-off second leg – and of The Little Bakery, makers of the World Champion Scotch Pie.

That none of the 80-odd entrants appears to have been from south of the Solway is simply unnecessary proof that it’s a very small world.

The plan was to catch up once again with the goalkeeper they called Big Allan – in the unlikely event that there be confusion with he of Blackpool and England – the sad discovery that he’d died last July, aged 75, minutes after being told that QoS had beaten Edinburgh City 4-0.

It filled the Scottish papers, made nothing here. We missed it – the best laid plans o’ mice and men gang aft agley, as Rabbie himself observed. We hasted back, nonetheless.

Allan Ball was an inside forward with Sunderland schoolboys, took the jersey when the goalie – some kid called Jimmy Montgomery – got injured, never again left his posts.

He played a few games for Bishop Auckland, a 15-year-old deputy for the great Harry Sharratt, had a short spell with Durham City but was never happier than at Stanley United – £5 a week as an apprentice at South Hetton pit, £6 in his boot from the Northern League amateurs.

“You could still be cold at Stanley in July,” he once recalled. “In that respect it was like Arbroath. I was never warm at Arbroath, either.”

He’d been on night shift when a scout called John Carruthers all but hollered down the shaft, came up share his corned beef sandwiches – it was 2am – and signed for £100.

Other familiar Northern League faces who crossed the border at much the same time included Arnold Cates, George Siddle, Michael Barker, George Brown and Jock Rutherford.

At first while still playing working down the pit, Allan made 819 Queen of the South appearances, 507 consecutively, was one of just two Englishmen to play for the Scottish League, ran a motors business in Dumfries and became an honorary club director.

In 20 years he was booked just once, by well-remembered ref Tom “Tiny” Wharton for a mild profanity. It was Christmas Day. You couldn’t blaspheme on Christmas Day, said Tiny.

We last met in 2008, QoS – managed by former Sunderland centre half Gordon Chisholm – having reached the Scottish Cup final after beating Aberdeen in the semi. Queen of the South 4 Cocks of the North 3, said the headline in The News of the World – and a great week for Allan.

A few days earlier he’d been given the all-clear after a direct hit from a golf ball caused cancer of the eye. “That was a big win, too,” he said.

His favourite memory was of a Scottish Cup quarter-final at Ayr, in which he was convinced he’d broken his leg in the first half.

Club chairman Willie Harkness insisted he continue, told the trainer to strap it up but not to take the boot off lest they couldn’t get it on again. Two down, the Doonhamers fought back to 2-2 but conceded a penalty with four minutes remaining.

Allan flung himself to his right, pushed it away. “People used to say it was a fantastic save but it was the only way I could go.

“I used to say to Johnny Graham, who took it, that it was goalkeepers who were supposed to be thick. If he’d put it on my crocked side they’d have been in the semi-final.”

Queen of the South won the replay, Allan watching from the stand with his broken leg in a pot.

Did he regard himself as English or Scottish, we ask in the Palmerston Park club shop last Saturday

“Baith,” says Archie McDonald.”

“Neither,” says Donald Cruickshank. “He was a Doonhamer.”

We’d interviewed John Carruthers in 1995, two years before his death. Born in Dumfries, he’d played briefly for Carlisle United under Bill Shankly, earned his badges as a scout at QoS and was persuaded to join Bobby Robson at Ipswich.

“I’m 69, been around a bit and never met a better man in football than Bobby Robson,” he said.

While unattached he’d also spotted the young Kevin Beattie, contacted Shankly – then at Liverpool – and was asked to send him down. Beattie missed the train, Shanks growled dismissively.

“Probably it didn’t help,” said John, “that Kevin got his bookmaker to make the call.”

The second border crossing came in 2000, when former Newcastle United full back John Connolly was appointed the Doonhamers’ manager and again looked to the Northern League.

We’d watched the Anglos in a pre-season friendly at Stenhousemuir, travelling fans not wholly impressed. “If we’d wanted a team of Geordies we could have signed Jayne Middlemiss,” someone wrote to the Dumfries and Galloway Standard.

Alex Wilson, the Palmerston Park PA man, had hoped the newcomers wouldn’t take offence at being called English bastards. “They call us English bastards,” he said, “and we’re from bloody Dumfries.”

Dumfries is a riverside town of 33,000 or so, the watchword A-lore-burne adopted by both town and football club. Translations vary, from “Stand by to repel boarders” to “Up to the oxters in clarts.”

Burns died there after several years of writing, drinking, chasing smugglers and sowing his porridge oats, his 13th child (approx.) born on the day of his funeral.

These days it’s more cosmopolitan. There’s a Polish shop, a Kurdish barber, an Italian ice cream place and a Chinese restaurant and no matter that both the barber’s and the restaurant are – see you – called Jimmy’s.

To add to the global appeal, the Kurdish barber’s on English Street.

The Little Bakery, globally triumphant, may not be small, either, It’s run from an industrial estate by Kerr and Neil Little, father and son, selling everything from macaroni pie to tattie scone rolls, from bridies to haggis and peppercorn sauce pies.

From the Upper Crust, a baker’s shop in the town, a chap carries six hot scotch pies, one on top of another in separate paper bags in the manner, proud and precise, of the chap bearing the Burns Night haggis.

Probably he says braw, but that can’t be verified.

The lady of this house supposes them a bit too greasy. I think they’re delicious but not greasy enough. We’re Jack Spratt and his missus, and that’s how we rub along.

The Globe Inn, much patronised by Burns himself, has temporarily been taken over by a group of Scousers, who may suppose it something to do with Kenny of that ilk.

What Rabbie would have made of their accents, or they of his, can only be imagined.

The Scottish Championship play-off doesn’t concern events at the top of the second tier, but the bottom. QoS, now managed by former Sunderland and Middlesbrough player Allan “Magic” Johnston – the last man to score a competitive goal at Roker Park – finished second last, above Falkirk on goal difference.

Raith, second in the third tier, trail 3-1 from the first leg of the play-off.

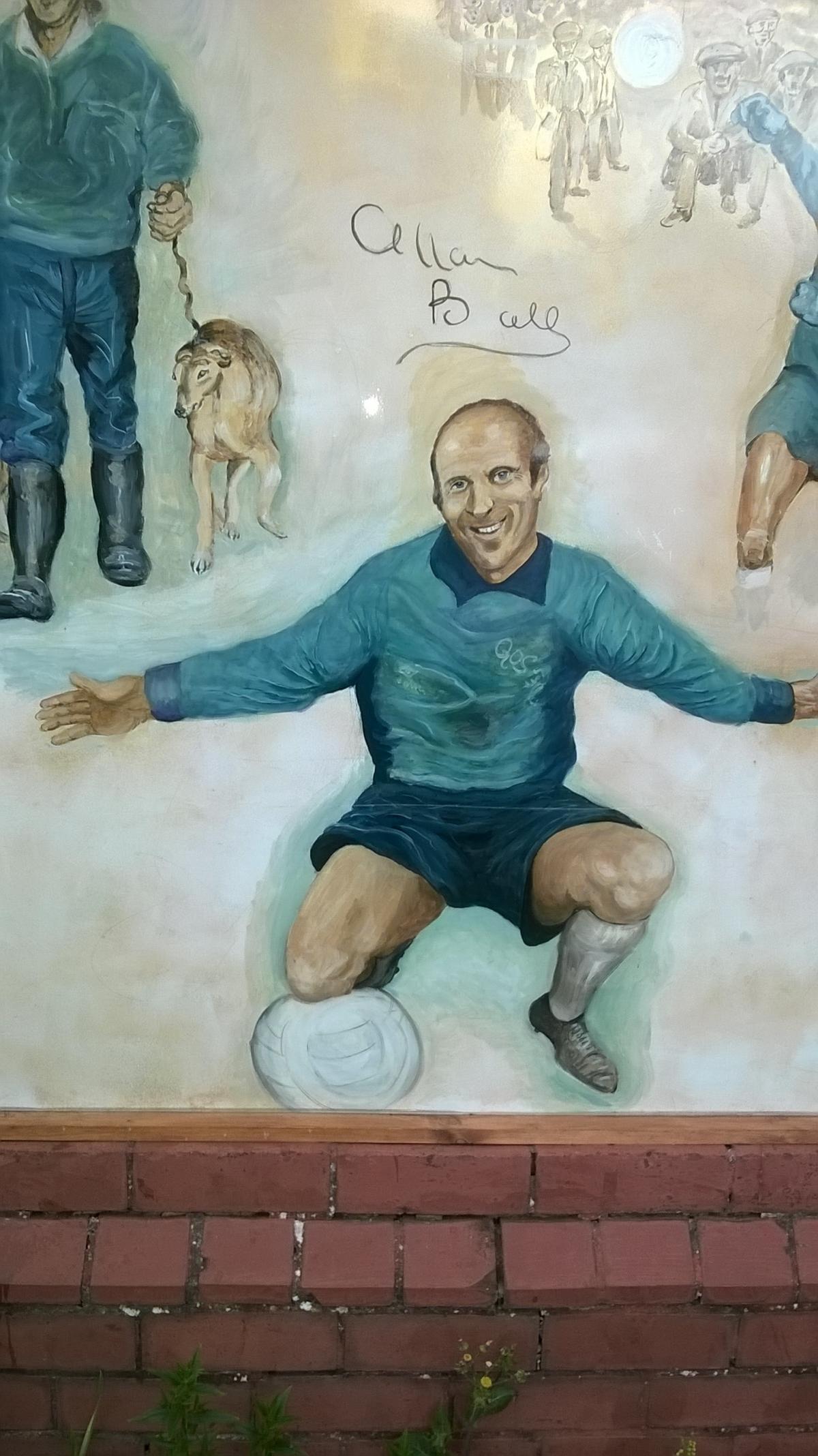

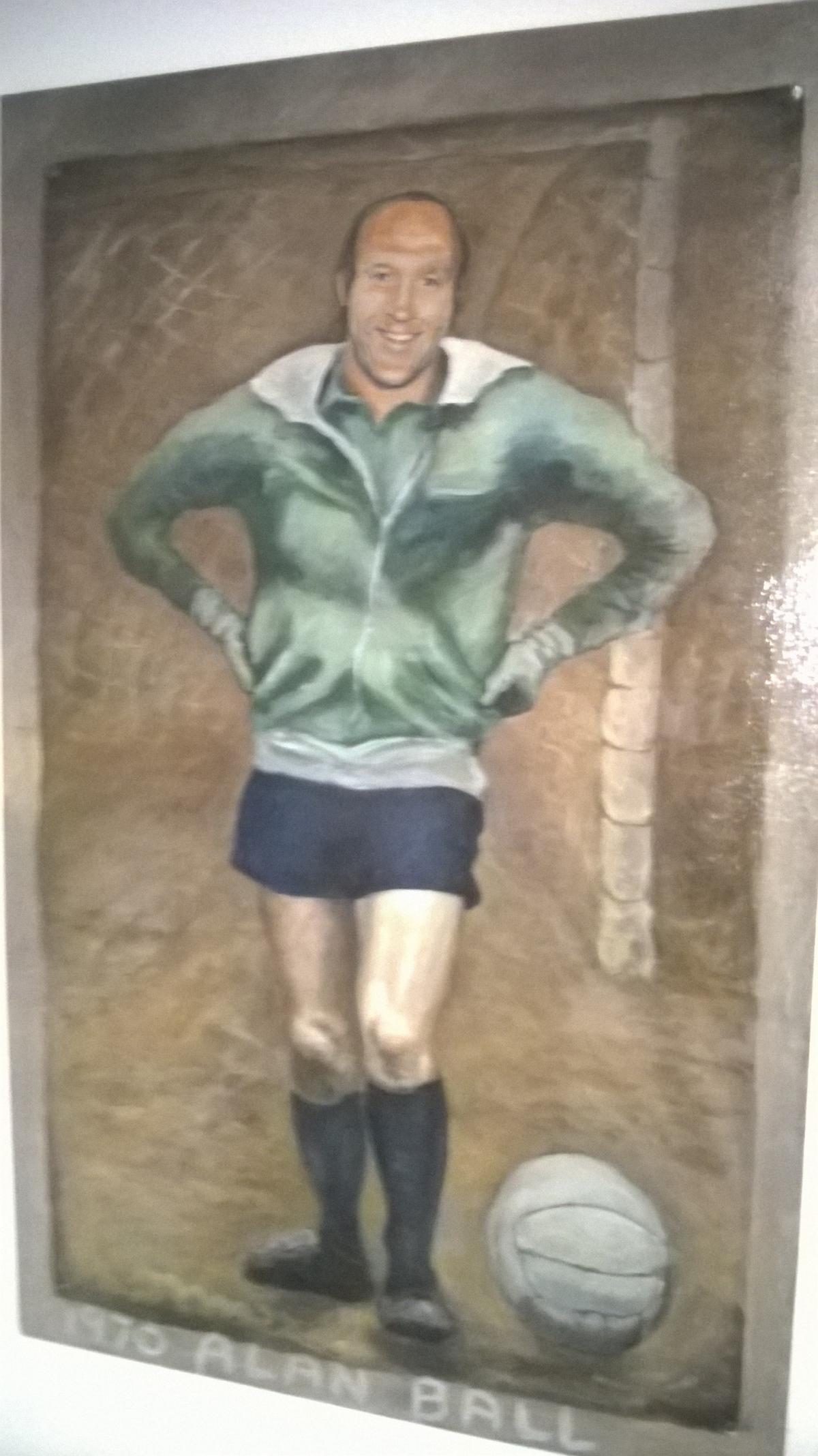

On the ground wall nearest the prison, a sequence of murals includes several of Allan Ball. There’s also a lengthy set of ground regulations – “large flags must be accompanied by a fire safety certificate.”

There’s another mural in the corridor near the club shop. “Other than Roy Henderson the best goalkeeper we ever had,” says Donald Cruickshank. Roy Henderson must have been some goalie.

The Palmerston Park crowd’s 2,240, barely a quarter full. Despite the exhortations of Dougie the Doonhamer, the mascot, the game ends goalless.

Queen of the South survive for another second tier season. Big Allan, bless him, would have been delighted.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here