LIKE Santa Claus three months early, but timed perfectly nonetheless, Mr Roger Jennings arrives bearing gifts.

Roger lives in Stockton, is headed to Richmond to stock up on Taylor’s pies, delivers four hefty volumes of a 1960 publication simply called Association Football, comprehensive from Arsenal to Zeppelin.

The Zeppelin connection was poor old ‘Pools, bombed during the war and said in the book still to be seeking compensation from whoever it was that did it.

It’s the day before a week’s break in Somerset – the county of Combe Florey, Huish Episcopi and of the Demon of Frome – and thus perfect holiday reading.

It may not be said that every word of those 2,000 well-illustrated pages has been digested – there are Quantock Ales to sup, the wonderful West Somerset Railway to explore, adopted county cricket about which to cavil – but it’s been hugely diverting, even so.

The temptation, indeed, was to head today’s column Jennings and Somerset, a nod to Mr Anthony Buckeridge’s schoolboy stories from another age, though they were Jennings and Darbishire.

The one above may just have to suffice.

THINGS were different in 1960. Managers wore trilby hats and trainers long white coats, goalies wore gloves only when it rained and players even smiled for the camera – so long ago that the book clings consistently to the O-level English notion that a football club is singular. Darlington plays – played – at Feethams.

The FA remembered the Sabbath but wanted nothing to do with it, the maximum wage was £20, the record transfer fee £45,000 for Albert Quixall, Manchester United fans could watch Bilbao in the European Cup for 3/6d and, the pools’ £75,000 ceiling recently raised, a widow woman won £300,000 for a stake of one-and-a-tanner.

The English game was also becoming a mite worried about Johnny Foreigner, and in particular Mickey Magyar and Bertie Brazil.

Geoffrey Green, co-editor and football correspondent of The Times, supposed that all we’d given football in the previous 30-odd years was a change in the offside law – from three defenders to two – and the long throw-in, credited to Newcastle United left-half Sam Weaver.

“British football in its style and tactics has found itself a prisoner for the past 30 years,” wrote Green. “The world has caught up and even passed us in performances.

“The British game has become sterile in thought and composition. What was good enough for their grandfathers is good enough for them.”

Six years later, England won the World Cup.

THOUGH not published by the FA, football’s encyclopaedia seemed greatly to bear its imprint. “A monumental work, every aspect of the game covered in a most exciting fashion,” wrote Sir Stanley Rous, the FA secretary, in the foreword.

Green also noted that in 1902 the Association had been run by a secretary and two clerks and that by the late 1950s it was “30-strong.” At the last count it employed more than 900.

The amateur game was extensively covered, chiefly by a gentleman called Norman Ackland who’d written as “Philistine” on the Westminster Gazette and as “Pangloss” in the News Chronicle and who appeared unalone in the belief that the game ended at Potters Bar.

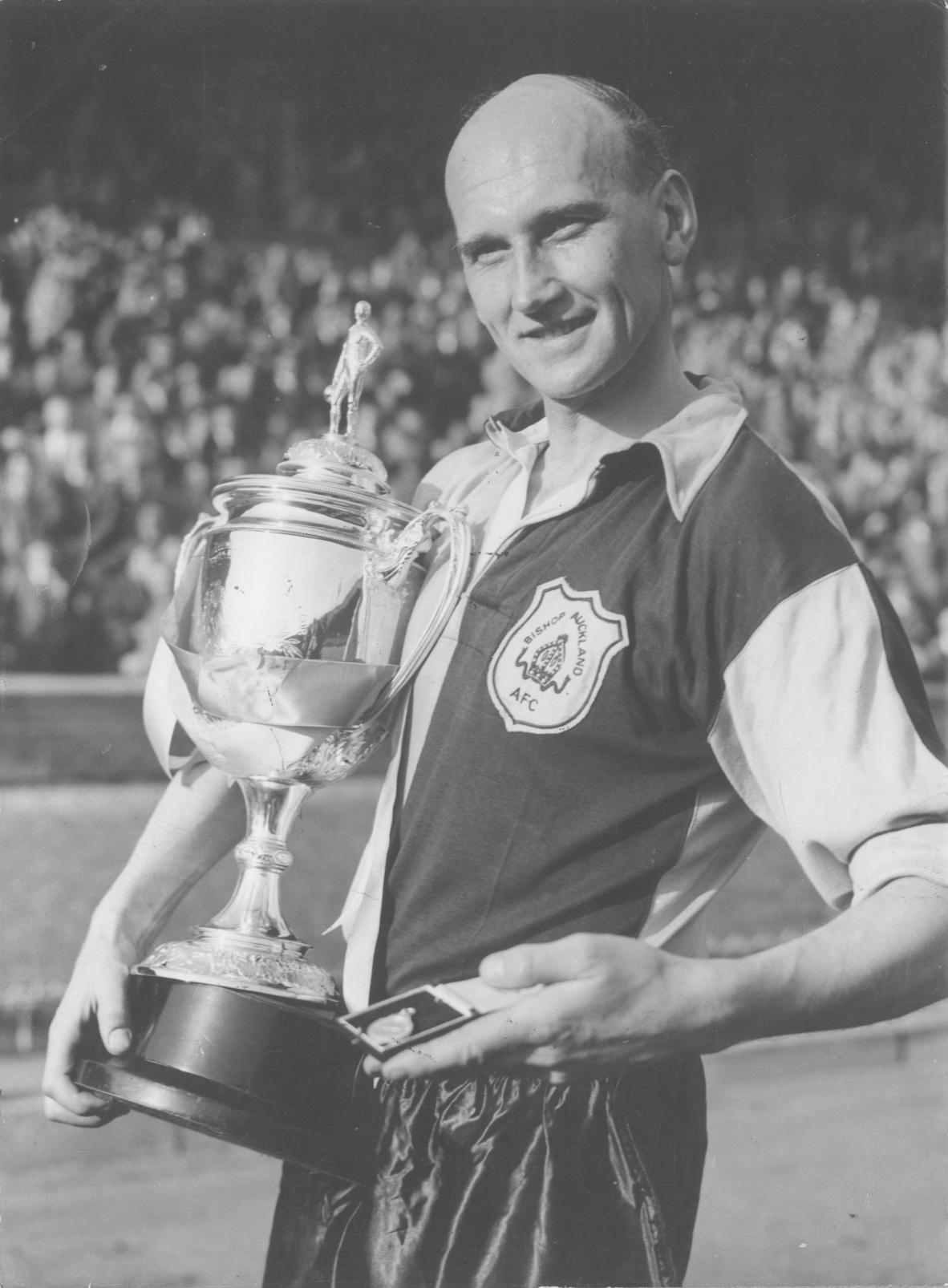

Though the great Bob Hardisty of Bishop Auckland was acknowledged as “the finest amateur of the past two decades”, the North-East warranted barely a mention compared with the second-best south.

The Isthmian League had 61 pages, with more on the Delphian, the Corinthian, the Spartan, the Hellenic, the Corinthian and very likely the Mickey Mouseian had such a competition squeaked within 20 miles of St Paul’s.

The Northern League, the world’s second oldest, was remaindered at the back of volume one in a 10-page afterthought headed “Some Northern and Midland teams.” The “northern” clubs included Bishops, Crook Town and Billingham Synthonia – “popular and progressive” – the Midlands had just one, Moor Green.

Those were the days, of course, when the FA was routinely accused of southern bias when choosing amateur international sides. Now we know why: they didn’t know the north existed.

FOOTBALL, Green supposed, may first have been played in China more than 2,000 years previously. By the 14th century, Edward II felt obliged to issue an edict outlawing “hustling with large balls.”

Sundry statutes followed over the years. “A useless and unlawful game,” supposed Richard II, though he thought the same of tennis.

Particularly it seemed popular on Shrove Tuesday, not least in Derby when 500-or-so from St Peter’s would take on a similar number from All Saints – hence, of course, the local derby.

A traveller from overseas is said to have remarked that if that was what the English meant by “playing”, heaven help them when they turned to fighting.

Such Pancake Tuesday insurrection continues unabated. Just ask the good folk of Sedgefield.

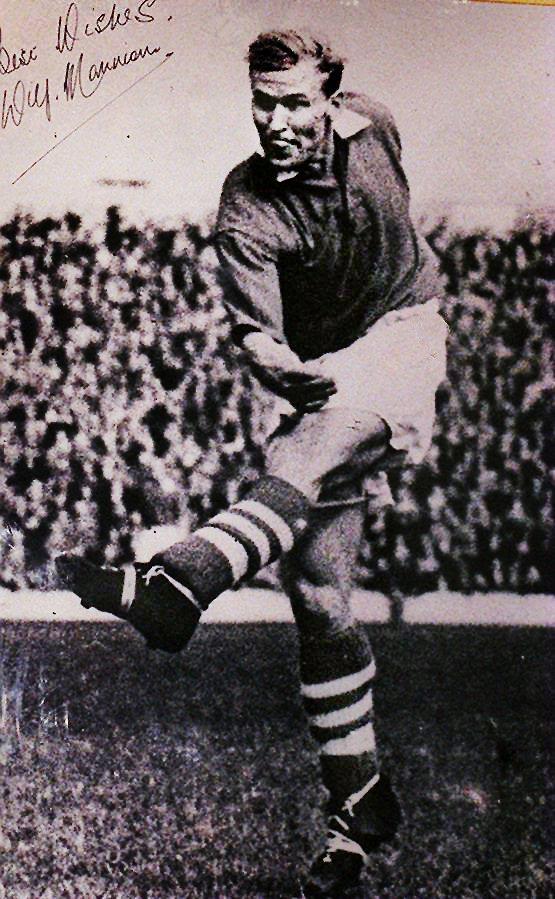

AMONG those invited to contribute to a section called “The match I remember” were Sunderland great Raich Carter and Wilf Mannion, the Golden Boy of the Boro.

Carter chose the 7-2 win at Birmingham City which gave Sunderland the first division title for the sixth, and last, time. Bobby Gurney hit three, Jimmy Connor two but it was Raich – “the wonder of the day” said the Sunderland Echo – who made everything possible.

Wilf thought his most memorable game the visit of Blackpool to Ayresome Park, November 22 1947, partly because Boro won 4-0 – McCormick 2, Spuhler, Fenton – and partly because a few hours earlier he’d become engaged to Bernadette, his bride-to-be watching her first-ever football match from the stand.

Whatever the future Mrs Mannion thought, the Echo the following Monday morning was greatly impressed. “Mannion’s twinkling feet were behind every goal,” our man wrote.

“Mannion made the ball do everything but talk,” said Blackpool manager Joe Smith.

“I reckon we were a side of miracle men, every man jack of us,” wrote Wilf. “To this day I doubt if Middlesbrough’s followers have seen a better game.”

NOVEMBER 22 1947? Newsprint was rationed, the Echo only briefly able to report Sunderland’s 4-0 defeat at Burnley, Newcastle’s 4-1 home win over Cardiff and away wins for Darlington and Hartlepool. That Wilf Mannion’s big announcement earned not so much as a mention may have been because the nation still demanded news of another romantic occasion two days earlier – the future Queen married her prince.

IN those 2,000 pages, Bill Murray – former Sunderland right back and manager from 1939-57 – may have been the most contentious.

He wanted to do away with promotion and relegation which, given Sunderland’s subsequent vicissitudes, may have been quite far sighted.

“We are stupid to regard football as a sport,” he wrote, no less presciently. “Really we know it is a business and often a sorry and a sordid one”

Particularly he remembered the last game of 1927-28 when, needing the points to escape relegation, Sunderland won 3-0 at Middlesbrough. The mood remained solemn.

“One did not feel in the mood for celebrating. It was like a victory against death. It has been said that football is only a game, but when you have walked through the shadow of the valley, one wonders.”

Ending promotion and relegation, Murray argued, would free funds for ground improvement, almost end the transfer market and place an emphasis on more quality. “P&R,” he argued, “restricts enterprise, creates stagnation and fosters the parochial outlook.”

Sunderland had gone down for the first time in 1958.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here