Arthur Puckrin, an athlete who took extreme sport to extremes, has died. He was 80, perpetually pushed back the barriers of human endurance but never quite answered the question “Why?”

Incredible, incorrigible, indomitable, his basic discipline was the Iron Man event, embracing a two-and-a-half mile swim, 112 miles on the bike and, to finish, a quick marathon.

For Arthur, however, the iron mantra was to do it in multiples that might giddy a primary school maths group, and he did it until well into his 70s.

Globally, almost gleefully, he’d tour the world in search of quad, tetra, deca. For Arthur a double-deca was like a busman’s holiday.

He’d represented Great Britain at seven sports, including bridge, held three overall world records and 30-odd for his age group, was slowed only by a carcinogenic cocktail of serious illness when 75 and, thus reminded of his mortality, finally proposed to Mary, his partner of 34 years.

They married three weeks later – “things were looking a bit serious” – honeymooned less than coincidentally in Aberdeen where he won five medals in a masters swimming championship.

In 33 years of the Backtrack column, richly privileged to have met many extraordinary sports people, there’s never been anyone quite as amazing as Arthur, the headmaster of the school of never-say-die.

Ray Mallon, the former elected mayor of Middlesbrough, was another admirer. “If we ever have a power cut on Teesside,” he once wrote, “we only need to hook him up to the National Grid and let his energy levels do the rest.”

We’d last met at Christmas 2014, Arthur reflecting that that it had all just been an exercise in hanging out with his mates.

“Exactly,” said Mary, “the same old crazy people.”

Paradoxically, however, the Iron Man’s unique life may best be summed with a non-corrosive cliché: it’s better to wear out than to rust.

He was born in Guisborough, grew up on the adventures of Wilson of the Wizard and (more appropriately) Alf Tupper, the tough of the track, left school with two O-levels, spent nine years as a Cleveland police officer while studying in his spare time to become a barrister.

His first arrest, he liked to recall, was of a lady and her client outside the then-notorious Robin Hood pub in an area the Boro boys call over the border.

“Will it end up in the paper?” asked the wretched gentleman, then as (very likely) now.

At 28 he was called to the bar, worked in the legal department at Dorman Long – appropriately for an iron man – believed in keeping fit.

He played rugby for Middlesbrough, was a pioneer of the 42-mile Lyke Wake Walk across the moors between Osmotherley and Ravenscar in North Yorkshire, though Arthur preferred to run it.

He five times won the annual Lyke Wake Race, held the record for ten years, completed a three-way crossing in 27 sleepless hours.

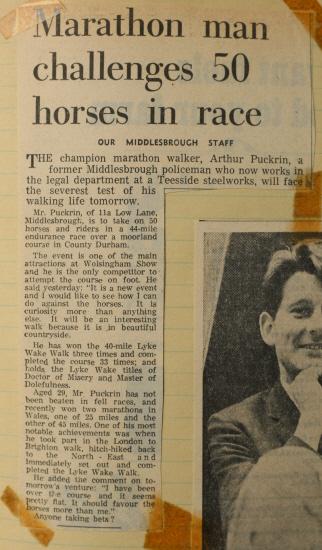

In the 1960s he’d also challenged 50 horses to a race around a specially designed course at Wolsingham – that one got in the papers, many of his exploits didn’t – and came second in the world coal carrying championships at (where else?) Guisborough gymkhana.

For 30 years, however, he withdrew from competitive athletics, though still finding time to take part in the world bridge championships.

“Bridge is every bit as demanding, probably more so, then endurance sports,” he once said. “”It’s certainly more vicious.”

Going to extremes may simply have run in the Puckrin family. Eleanor Robinson, Arthur’s sister, is a former world 1,000-mile record holder who a few weeks ago broke her hip after falling off her bike while training for the world duathlon championships – but Eleanor’s a mere 70 and vows soon to be back in the saddle.

When Arthur returned to competitive sports he – of course – sought to go the extra few hundred miles. Ultra-events took him all over the world, often to Mexico (“a bit like South Bank, only hotter”) where the winner’s trophy was frequently in the form of an Aztec sculpture commemorating human sacrifice.

It seemed rather appropriate, he’d say.

It could be just about the only material gain, sought or received, though they once gave him a Mexican hat, too.

On one occasion he fell asleep while swimming, on another the organisers thought he’d died, on several more he almost wished that he had.

Then there were the bears, the poisonous algae, the things that went thump in the night.

During one event, in 95 degree heat in Hawaii, he’d completed a 24-miles swim, 1,120 miles on the bike and a 262 mile run. “It was the most agonising two weeks of my life. I craved sleep, absolutely longed for it,” he recalled.

Another time – one of those double-deca busters – he’d had to take a day out of the 48-mile swim (“wiped out by a bug”) and started the 2,200-mile cycling event 120 miles behind his two chief rivals. “It didn’t worry me. I had 2,000 miles in which to catch up,” said Arthur. He won.

While others might have been counselled by a team of sports scientists and dieticians, Arthur might start the day with three slices of jam and bread – “slipped down beautifully, all those carbohydrates” – supplemented by Kit-Kats, Milky Ways and frequently invigorated by ice cream.

“Many a time when he was utterly exhausted, I’d promise him an ice cream if he did just one more lap. You’d be surprised how big a part ice cream played in all this,” said Mary, who frequently followed his footsteps.

“The division of labour was simple,” said Arthur. “I did the swimming, cycling and running. She did everything else.”

They’d met at the rambling club, Mary six years his junior, had two sons but didn’t marry until May 2013. Having proposed from his hospital bed, Arthur planned the wedding – at Nunthorpe Methodist church, near Middlesbrough – from it, determined to walk down the aisle without sticks. One son was best man, the other gave his mother away.

It was during an operation to insert a pacemaker (of all the medical improbabilities) that his thigh bone was accidentally broken, discovered to be cancerous and replaced.

Arthur then contracted the novovirus, spent several days in isolation and copped for blood clots on his lungs. Four major operations followed. “I’m a very lucky man. Even when I got poorly, they found it all at once,” he said.

Though cycling became greatly limited and running impossible, he was 77 when winning seven medals at the Scottish masters swimming championships.

After marriage they moved from Acklam to Mary’s home in Norton-on-Tees, north of the river, where recuperation was spent writing Racing Through Life, a 325-page autobiography. Some suggested that it should be made into a film.

“They were quite serious,” said Mary. “Sean Connery as Arthur, Helen Mirren as me. I’m not sure that anyone would have believed it.”

He’d long been in the final straight, determined to pass 80 – achieved in May. His funeral’s at Teesside crematorium at 11.15am tomorrow. “Three hymns and a party,” said Arthur.

To the last, the great headmaster of the never-say-die school of ultra-achievement came no closer to answering the eternal question than he did in 2008. Why, Arthur? “I suppose I must rather have enjoyed it.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here