WHEN Josh Gray signed youth terms with Darlington in 2008, he always hoped it would prove a life-changing moment. It was, just not in the way he had envisaged.

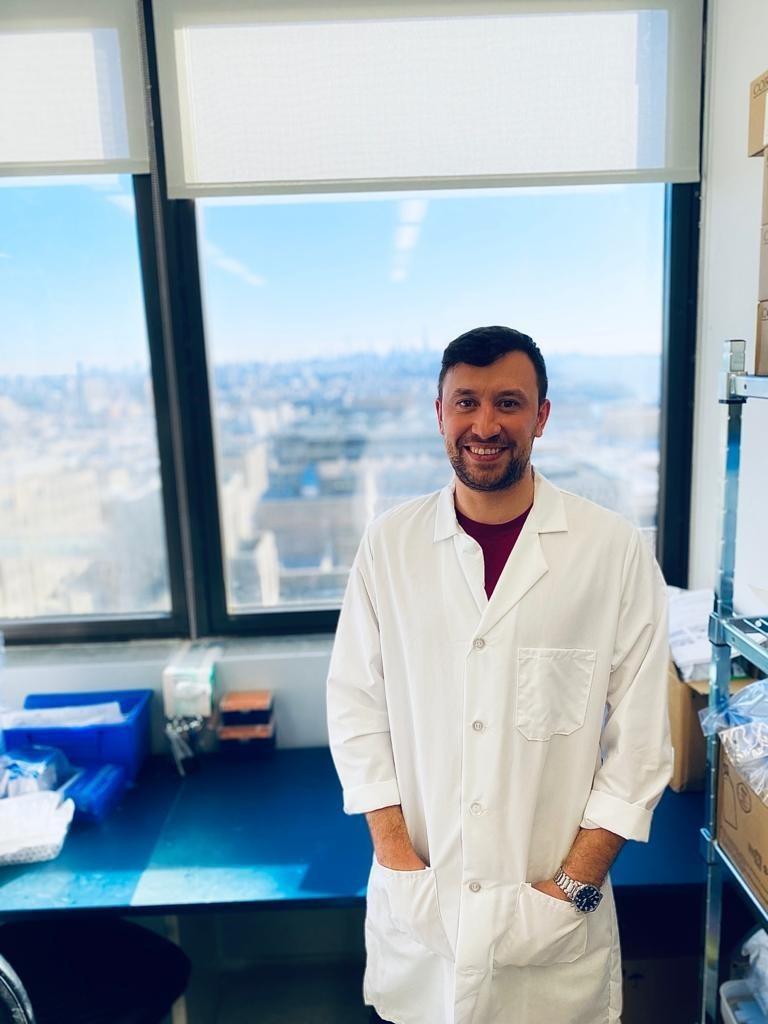

Gray, as he is happy to admit, was a decent enough footballer without ever being exceptional. After 49 senior appearances for Darlington, his sporting career was over. But while the football field might no longer be his workplace, he would not be where he is today, gazing out at the Manhattan skyline from his laboratory in downtown New York, had it not been for the opportunities that football helped create. No longer trying to break down defences for the Quakers, a now 29-year-old Gray finds himself spearheading some world-leading research into the genetic peculiarities of coronavirus.

“When I joined Darlington on a YT contract, I was enrolled onto a college course at Darlington College,” said Gray. “It was a National Certificate in sporting excellence – physiotherapy, massage, coaching, that type of thing – and then when I signed a two-year pro deal at 17, I was offered the chance to turn the National Certificate into a National Diploma, and that took me down more of a scientific route. By the time the two years were up, it was time to make a decision – football or science. I knew I was never going to make it as a top footballer, but I thought maybe I could make a career in science.”

Having received an educational grounding at Darlington College, who continue to work with young footballers today in a partnership with the Martin Gray Football Academy, Gray completed a higher education foundation course at Gateshead College before moving on to Northumbria University to study for a degree in biomedical science.

Having become interested in immunology during a vocational course in Sunderland in 2014 – you could say he was bitten by the bug – Gray was accepted for a PhD at Glasgow University. He was still playing football at that point – “I would travel down from Glasgow every weekend to play Northern League with Consett. I loved it but then the summer before my final year, I came down for pre-season and was about 80 miles off the pace. That was when I knew I had to hang up my boots for good” – but his primary passion was medical research.

His PhD project investigated immune responses related to arthritis, and his work resulted in him being offered a position at a laboratory and research facility based at the New York Presbyterian Hospital and linked to Columbia University.

He emigrated to New York with his wife on January 28 last year. On January 30, New York reported its first positive case of coronavirus. Like the rest of the world, Gray’s life was immediately turned upside down.

“From a personal point of view, it was a really stressful time,” he said. “We arrived in New York and within a week or two, the whole city was in lockdown. We didn’t even have our own flat at that stage.

“Luckily, we got something sorted, and from a work perspective, it was a once-in-a-lifetime moment really. For a month or two, New York was basically the worldwide epicentre of the pandemic. The hospital where we working was unreal. You looked out of the window and it was just ambulance after ambulance. You looked along the corridor and there was just beds everywhere. The research work we had been planning to do was placed on hold, and I got an Email from my director saying, ‘Right, we put all of our energy into researching this new disease’.”

The coronavirus pandemic has impacted everybody’s lives. Clearly, Gray would not wish the disease on anyone. But from the perspective of an immunologist, the once-in-a-generation event we are living through throws up opportunities as well as heartache.

“As a scientist working in this kind of field, you have to be able to detach yourself from the horror of what’s going on around you,” he said. “The harsh reality is that because New York was so badly hit, we had access to a lot of seriously ill patients.

“We set up a programme to obtain nucleus and blood samples from people who had very serious lung problems and were on mechanical ventilation. Unfortunately, about half of those people went on to die, but it meant we were able to look at whether a certain cell type was linked to the reactions that occurred in the people who died as apposed to the people who recovered.

“We were able to make some pretty exciting findings, and our paper was published last week. There are a couple of companies that have already started looking at developing therapies that would block the cells from being able to damage the lungs. Potentially, that could be transformative in terms of limiting the damage caused by Covid.”

Gray’s work is changing lives, and for all that he might once have dreamed of strutting his stuff at Blackwell Meadows or the Arena, or potentially at an even higher level in the professional game, he is proud of the different direction he headed in.

“I could have carried on playing football, but that would have been completely self-serving and just for me,” he said. “I didn’t want to look back on the last ten years and think, ‘I could have made a difference if I hadn’t been so selfish’.

“The Darlington College course was the starting point for me. Martin (Gray) got in touch and asked me to do a talk with some of this year’s students, and I just told them to take all the opportunities they’re offered. You never know where your life might end up.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel