Chapter 14

The railway was up and running. The first train, triumphantly pulled by Locomotion No 1, had passed along the 20 miles from Shildon to Stockton via Darlington on September 27, 1825 – the culmination of seven decades of argument and ten years of overcoming obstacles.

Now the real work began: to make the railway a success.

The initial signs were poor. In the week before the railway’s opening, every shareholder had been pressed to pay another £100. The company was so much in debt that it could not afford to begin work on its planned branchlines to Coundon or Croft. But without these branchlines, its chances of making money were limited: the Coundon one was needed to collect coal from the Dene Valley mines; the Croft one was needed to sell the coal into North Yorkshire.

In fact, the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) found itself in the position of having to compensate the owners of the Coundon mines because they still had to use horsepower to drag their coal to the incomplete railway.

In 1826, the S&DR approached the Government’s Exchequer Loan Board, which provided money for public projects. About £50,000 was asked for (about £1.64m in today’s money): £30,000 to repay debts; £20,000 to build the branchlines. Presumably because it thought the railway was an imprudent investment, the board refused.

So short of money was the S&DR that in January and March 1826, Edward Pease had to personally pay the workmen on the line – the wage bill came to £1,000 a time. On July 28, 1826, Edward’s son, Joseph, gave the company £1,305 19s to build inns at Stockton and Darlington to accommodate rail passengers.

And in May 1826, treasurer Jonathan Backhouse spoke of the company’s “pecuniary embarrassments”.

Then there were rolling stock problems. The company’s second engine was Hope, built by Robert Stephenson and Co, in Newcastle. When it arrived, in November 1825, it was in such a bad condition that Timothy Hackworth and his men spent a week taking it apart before it would start.

The S&DR’s resident engineer, Thomas Storey, reported that the 150 wagons were “as bad a set of wagons as were ever turned out on a railway”, and the one early triumph – the first coals from Old Etherley colliery were loaded on to the Adamant brig at Stockton on January 24, 1826, for export to London – was marred by Storey’s report in February 1826 that the staithes at Stockton were so poor that the company was like a “ship without sails”.

Indeed, even in these early months, Stockton was proving to be the wrong choice for a port. The river was too shallow, and keelmen had to row the coals from the quayside to the ships moored upstream. Already there was talk of moving the port to deeper water – Haverton Hill on the north of the Tees was first suggested, although soon the small hamlet of Middlesbrough would become the first choice.

All of these problems were costing the railway money, and so one of the key dates in these early years was March 1826, when Joseph Pease married Emma Gurney.

The Gurneys were Quaker bankers from Norwich. Emma, the younger sister of Jonathan Backhouse’s wife, was co-heiress to their fortune. Through the Quaker network, the Gurneys had been financially involved in the “Quaker line” since 1818. Just before the opening of the line in 1825, they had demanded instant repayment of some of their loans. After the marriage, they became more understanding, and advanced more money to help finance the Black Boy line, which opened on July 10, 1827, connecting the collieries of Black Boy, Coundon, Eldon, Adelaide and Deanery.

As important as the cash was the influence. Later in 1827, the S&DR asked for parliamentary permission to extend into Middlesbrough. This would clearly threaten the supremacy of the Tyne and Wear as coal exporters, where Lord Londonderry and the Earl of Durham had vested interests. Londonderry and Durham mobilised opposition in the Lords, but the S&DR had the Gurneys, who turned out the landed gentry from Norfolk and Leicestershire to safeguard their investment. In May 1828, the S&DR was allowed to head for Middlesbrough – and a more secure future.

Rough ride for the early passenger service

Passengers were not part of the Stockton and Darlington’s initial plan. The line was all about moving coal. People were an after-thought. In fact, there was little demand for passenger transport.

When the railway opened, there was one horse-drawn coach plying for trade between Darlington and Stockton, and the coach which did the run from Barnard Castle to Stockton via Darlington was off the road due to lack of business.

Nevertheless, on October 14, 1825, the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR), loaned Thomas Close £25 to buy a horse and a harness which he hitched up to the Experiment, and began passenger journeys along the line.

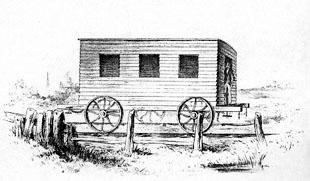

The Experiment was the “luxury” coach in which the directors had travelled on the opening day.

It seated up to 18 people on two wooden benches, and was little more than a shed on wheels.

Now Thomas Close began charging 1s for a journey from Darlington to Stockton, and so the poster advertising the start of his service can claim to be the world’s first passenger railway timetable.

Either because of its financial problems, or because of a Thatcherite business strategy, the S&DR in its early days believed in contracting out as much as possible.

Even the drivers of the S&DR’s own engines were sub-contractors paid a farthing per ton of coal carried a mile out. From that money, they had to pay for their own stoking coal and oil, and employ a fireman.

The in-house Experiment passenger service clearly did not fit into this ethos, and in April 1826 the coach was fitted with 16 mahogany panels and rented out for £200 a year to Richard Pickersgill, a booking agent, of Commercial Street, Darlington.

He installed seats for a further 12 passengers on top of the Experiment (fare: 9d).

Pickersgill clearly felt there was money in this passenger malarkey, for in the same month he put a horse-drawn coach called Express on the rails.

“More comfortably fitted up than the former one, being lined with cloth,” he advertised.

“Unparalleled cheapness, safety and expedition.”

His fares rose, though, to 2s inside and 1s out.

Other operators were enticed on to the line. In July 1826, Martha Howson, of the Black Lion Inn, Stockton, teamed up with Richard Scott, landlord of Darlington’s King’s Head, to put two coaches named Defence and Defiance on the line.

And in October 1826, The Union – “the elegant new railway coach” – began travelling the line using pubs, like the other coaches, as stations.

This proximity to alcohol was a big problem for the early passenger operators, as was the fact that the Stockton to Darlington line was a single track with only four passing places.

Horse-drawn passenger coaches had to give way to steam-powered locomotives, but when passenger coach met passenger coach head-on, it was a free-for-all.

With passengers egging on their driver, who may or may not have been drinking before setting off, it became a battle of wills to see who would give in and back into a siding. Naturally things regularly turned violent.

There are numerous tales of men madly chasing stagecoaches – and even locomotives – clambering aboard and giving the driver a good thrashing.

“Gentlemen, I only wish you to know that it would make you cry to see how they knock each other’s brains out,” Timothy Hackworth told an S&DR meeting in 1826. On one occasion, to save face, after a stand-off lasting a couple of hours, fed-up passengers decamped from one coach and hauled their rival off the lines.

Then, when their driver had victoriously passed, they dragged the humiliated opponent back on to the rails.

And yet, although the numbers were small, the concept of passengers travelling for pleasure began to take off.

The Union coach’s advert promised that on fair days in Yarm it would be running special services, and in August 1826, the Defence coach carried a record 46 people in one journey to Stockton races.

Nine were on the inside, 37 on the outside.

“Of these, some were seated round the top of the coach on the outside, others stood crowded together in a mass on the top and the remainder clung to any part when they could get a footing,” said a witness.

Perhaps there might, after all, be something in this passenger transport idea.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here