Many of the region's great houses have disappeared, while some are still there but not easy to find - even with a map. Echo Memories looks at the history of some of County Durham's hidden gems.

WHERE have all the halls and houses of northern County Durham gone? In truth, although many have been lost, others can still be seen here and there, often overlooked or unnoticed because they have not become tourist attractions, like many houses in other parts of our nation.

The grander country houses of County Durham were symbols of success for Victorian businessmen, or prominent homes, built to reflect the status of the landed gentry. Some have survived, occasionally appearing in "star buy" advertisements promoted by local estate agents. Others, abandoned, have been converted into public buildings or perhaps hotels after falling into disrepair. Some were damaged beyond hope and have been demolished and lost.

There are great variations in grandeur. What might be called a "hall" on the map can turn out to be little more than a large farmhouse, while some grander mansions are more modestly described as houses.

Among the grander mansions that still survive are Mount Joy and Burn Hall, both to the south of Durham City. Burn Hall, near Croxdale, dating from 1821, is certainly one of the grandest. Designed by Durham architect Ignatius Bonomi, it was one of two prominent halls in the neighbourhood owned by the Salvin family, the other being the older Croxdale Hall, a beautiful, older and more rustic building. The Salvins have lived in the area since 1409 and Croxdale Hall, dating from the 1700s, is still in the family's ownership. It comes complete with two chapels. One is a modest medieval building in a field overlooking the hall, and the other is a Gothic chapel of 1807 that forms an extension of the hall. Beautiful parkland surrounds Croxdale Hall and Burn Hall. Queen Victoria, glimpsing Burn Hall from the train, is said to have declared it the finest looking estate between the Humber and the Tweed.

Looking after one mansion, let alone two, became a burden for many families in a more modern age and many grand halls were sold off or demolished. In 1926, Burn Hall was one such building that was sold off. The new owners were Roman Catholic missionaries who used it to train boys as missionary priests. It continued under their ownership for many decades but, by 1995, costs were running high and it was sold again. The building remains intact, but is now divided into apartments whose occupants can enjoy the wonderfully scenic parkland, as well as easy and convenient access to the neighbouring Great North Road.

Mount Oswald Manor, now a conference and corporate facilities venue with a golf course near the A177, vies with Burn Hall for its grandeur.

Originally called Oswald House, it was built in about 1800 for a London merchant called John Richardby, who sold it to Thomas Wilkinson, of Brancepeth, a one time Mayor of Durham, in 1806. It was not really developed on the grand scale we see today until 1828, when it was acquired by Wilkinson's cousin, the Reverend Percival Wilkinson, of Belmont who employed the architect Philip Wyatt to build the mansion in a style reminiscent of Bonomi.

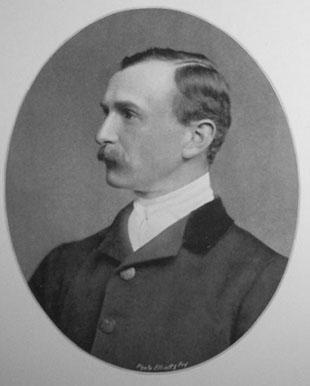

By the 1890s, it belonged to the North Brancepeth Coal Company and then Captain John Rogerson, of Croxdale, a director of the Weardale Steel, Coal and Coke Company. He was a master of the North Durham Fox Hounds, as well as a JP, deputy lieutenant and high sheriff. It was in 1920 that the house and its grounds became home to a golf club.

The house at Mount Oswald is still there to be admired, unlike its neighbour, the second Oswald House. Built by George Wilkinson, the son of the Thomas we have mentioned, it was just to the north, on the other side of the A177, on a site now more or less occupied by Collingwood College.

In 1866, George accidentally, rather carelessly, shot himself dead and the property passed in succession to his sons George, the Bishop of Truro, and his sibling Thomas Chandler Wilkinson.

The house later belonged to a coal owner called Robinson Ferens JP. During the Great War, it served for a time as a hospital before passing to an industrialist called Sadler.

Sadly, it burnt down in the Sixties and was never rebuilt.

Old mansions and manor houses often find themselves reborn as hotels and the best known of these is undoubtedly Ramside Hall, to the east of Durham City which, like Mount Oswald, also plays host to a notable golf course. The estate on which it was built stands on land long known as Ramside that was once part of the lands of the medieval hospital of Kepier, near Durham. It was later Heath land - land belonging to the Heath family, who bought the land following the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1500s. Later still, it was home to the Smiths, and then the Gowlands, in the 1700s.

A farm called Ramside Grange stood here, but the hall itself began life as Belmont Hall in 1820, when Thomas Pemberton, a member of a family who had made their fortune in coal, built the new hall.

Pemberton coal interests were in the east of the county and one branch of the family was most notably associated with the massive Monkwearmouth Colliery, one of the most important in the region. This colliery was known in early times as Pemberton Main and stood on a site now occupied by the Sunderland Stadium of Light.

The name Belmont that was adopted for the Pemberton mansion, near Durham, was a fanciful French way of emphasising the beauty of the site and it was a name that would ultimately be adopted by the extensive Durham City suburb of that name.

Today, Belmont Hall is known as Ramside and is best known for its hotel and golf course. It is lucky to have found a purpose, as many old halls and houses in Durham have been forgotten and lost - as we will discover when we continue our exploration of Durham houses next week.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here