FROM late November 1943 the men of the US 9th Infantry Division started to arrive in Winchester, only months later they were catapulted into the largest amphibious invasion of all time, D-Day.

After campaigns in deserts of North Africa and the mountains of Sicily, the US 9th infantry was sent to Hampshire.

Here the division set up headquarters in Winchester and surroundings towns to which they would call home for the next seven months.

This was not the first time American soldiers had set foot in Winchester. Over two decades before, American soldiers - known as Doughboys - had been stationed near the city before their journey to the trenches of France and Belgium during World War One.

They had been based at an encampment at Morn Hill, but this group of American soldiers in 1943 where part of the community at places such as Upper Barracks, renamed to Peninsula Barracks in 1964, and West Downs School on Romsey Road, now part of Winchester University.

For all men stationed at Winchester, there was a mandatory information course to teach soldiers basic good manners and to acclimatise them to English mannerisms and customs. This was then followed by an examination, and for the ones who passed, daily passes were issued allowing them to visit Winchester and other cities.

Many of the soldiers were impressed with the beauty and history that Winchester had to offer, attractions such as the castle and cathedral were a big hit with many soldiers, including Sergeant Joseph Bergin of F Company, 47th Infantry Regiment.

Bergin, from Boston, entered service in 1942, participating in the Sicily campaign during Operation Husky. He arrived in Alresford in November 1943, from here he would often visit Winchester and its cathedral.

READ MORE: The history of a famous speech at Cheesefoot Head by Dwight Eisenhower

Speaking about his time in the city, which was published on 9thinfantrydivision.net, he said: “I have fond memories of my visits to Winchester. The people there were very friendly. I was so amazed by seeing the cathedral there. It didn’t look anything like a church back home. It breathed history. I attended a couple of masses in the cathedral as well. It was so impressive to see the large buttresses inside. I kept looking up during mass and admired the interior.

"I would also wander through the streets and have a look at the sights and do some shopping. I remember they handed out a city tour leaflet as well, and I think I visited nearly all of those sights on there”.

The servicemen could also enjoy Red Cross-organised clubs and shows put on for them by the United Services Organisation.

Winchester was also home to a selection of pubs and shops which helped to make the men feel at home, as mentioned within Chief Warrant Officer Frank Lovell's personal diary from December 1934.

He was drafted in 1940 and took part in several battle campaigns.

On December 4, 1943, he wrote: "I got up for breakfast this morning for a change. I went to division with Ransdell and Captain January, which is at Winchester. It was cold.

"We stopped in Winchester and bought some brooms and hangers at a hardware store. It was nice to see store windows and see them full of things and Christmas decorations. And great to see and hear people who could speak English. It was nice to see the sights, and there are some nice-looking girls around”.

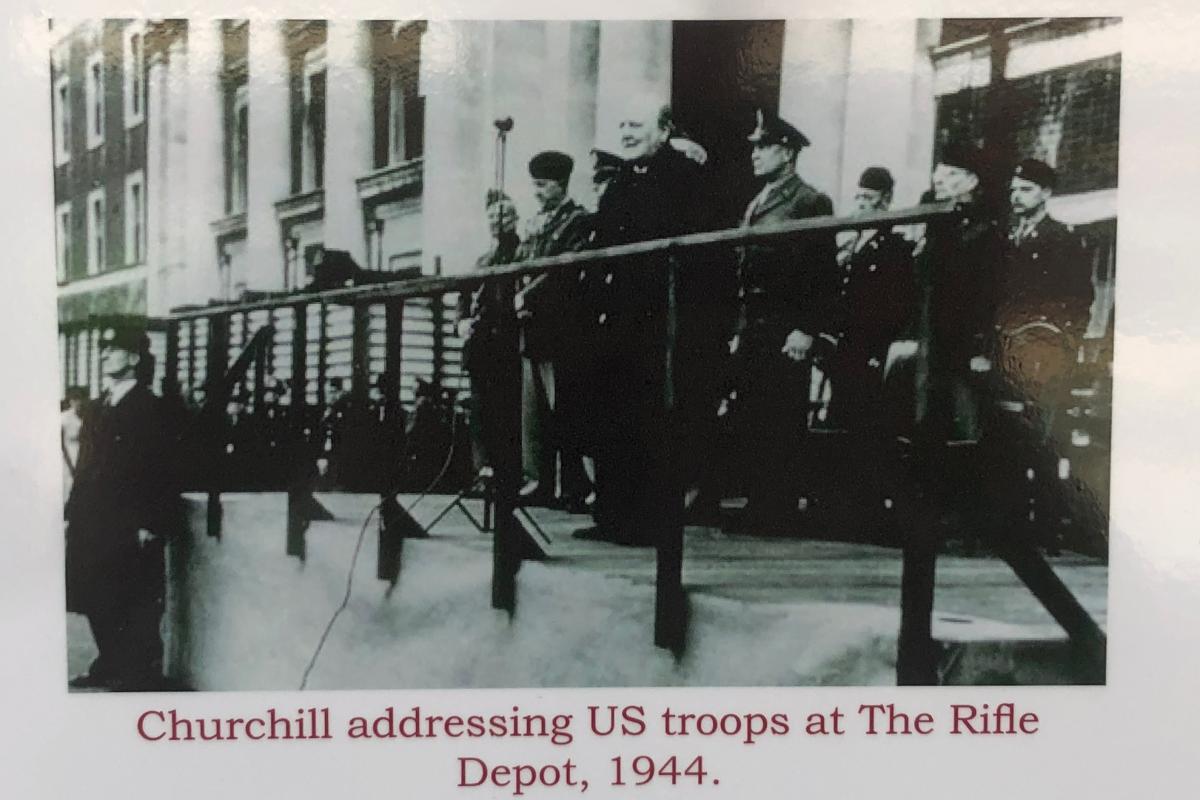

From Winchester, the divisions preparations for an invasion of the continent started to accelerate, In January 1944, the Commander in Chief of the Allied Ground Forces, Bernard Montgomery addressed the 60th infantry based at Peninsula Barracks followed in March by inspection from supreme allied commander (and eventual 34th president) Dwight D Eisenhower, Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

In May, the whole division was put on six-hour alert status, which could only mean one thing, the start of invasions preparations had begun. On June 3 they were moved to Hursley Marshalling camps (C12 and 13) from which they were barred from leaving and communicating with the outside world.

After being alerted that the invasion had begun, the men of the 9th were moved into Southampton. From here they would travel to the Normandy from the docks on June 10 (D-day plus 4) and participate in the breakout of the Normandy beachhead.

Many never got home.

For more go to 9thinfantrydivision.net/

A message from the editor

Thank you for reading this article - we appreciate your support.

Subscribing means you have unrestricted access to the latest news and reader rewards - all with an advertising-light website.

Don't take my word for it – subscribe here to see for yourself.

Looking to advertise an event? Then check out our free events guide.

Want to keep up with the latest news and join in the debate? You can find and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here