THE 700th anniversary of one of North Yorkshire’s most significant battles, which features one of the most excruciating deaths of all time, is to be commemorated this weekend.

The Battle of Boroughbridge took place on March 16, 1322, where the Great North Road crossed the River Ure, and ended with one nobleman being flukily disembowelled, another being famously hanged in York, and with King Edward II (below) finally ridding his kingdom of a northern earl who had caused him problems for a decade.

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, was the second richest man in England after his cousin the king, and he had become the leader of discontented noblemen who were opposed to the weak king.

At the Battle of Burton Bridge in Staffordshire on March 10, the king’s army had defeated Lancaster, who returned to his stronghold of Pontefract castle. Edward went after him, and Lancaster – who was in alliance with Robert the Bruce, the Scottish king – retreated north.

But Sir Andrew Harclay, Earl of Carlisle, collected 4,000 royalists from Cumberland and Westmoreland and moved east to intercept him, taking command of the north side of Boroughbridge’s timber bridge over the Ure and a nearby ford.

When Lancaster arrived, he faced a terrible choice: take on Sir Andrew so he could cross the bridge and continue north, or turn south and take on the king’s army.

He chose to fight Sir Andrew, who organised his pikemen into a new schiltron formation – a shield wall – on the bridge, and placed his longbow archers to defend the ford.

Lancaster had about 700 knights and a couple of thousand men. They attacked in two columns. Lancaster led the charge against the ford, while Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, and Roger de Clifford, lord of Skipton, attacked the shield wall on the bridge.

The archers rained down such a torrent of arrows on the ford that Lancaster’s men were forced to retreat, while on the bridge Clifford was “sore wounded in the head”.

The unfortunate Hereford suffered a worse fate. A chronicler, who was sympathetic to him, recorded: “As the noble lord stood and fought upon the bridge, a thief, a worthless creature, skulked under the bridge, and fiercely with a spear smote the noble knight into the fundament, so that his bowels came out there.”

It would seem that Sir Andrew had deliberately stationed beneath the bridge some of his pikemen. They were armed with their long spears, one of which penetrated the Earl of Hereford’s backside, killing him on the spot. This scene is memorably depicted during the Kynren live show at Bishop Auckland.

The battlecross at Aldborough which commemorates the Battle of Boroughbridge

It seemed to knock the fight out of the rebels, and the king’s men rounded them up the next day.

Lancaster was taken back to Pontefract Castle where he was rapidly tried, found guilty of treason and beheaded on March 22.

About 30 other rebels were also executed, including Roger de Clifford, who was taken to York Castle where he was hanged in chains from the castle’s largest tower on March 23. That tower is today one of York’s greatest attractions and is, of course, called Clifford’s Tower (below) in his honour.

The victory at Boroughbridge could have been a decisive moment for Edward II. He had crushed the man who had been gnawing away at his reign for years, and then he turned his attention on Robert Bruce. However, his invasion of Scotland in August 1322 ended in ignominy when his army ran out of food and, famished, had to retreat.

This encouraged the Scottish to sweep south after them, ravaging the north of England. Edward holed up in Rievaulx Abbey until October 14, when his army was defeated at the Battle of Byland, forcing him back to York.

Unfortunately, he had left his wife, Queen Isabella, at Tynemouth Priory, and she had to escape the Scots by an unpleasant sea journey. She turned on Edward and in 1326 with her lover, Roger Mortimer, deposed the king and replaced him with their son, Edward III.

Some sources say Edward II died in Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire in 1327 of natural causes while under arrest. Other sources say he died in the manner of the Earl of Hereford on Boroughbridge bridge – only with a red hot poker, inserted in the same fashion, being the deliverer of death.

ON Saturday, the Boroughbridge & District Historical Society has arranged a day of commemorative events with the Battlefields Trust.

It begins at 9.30am with a wreath-laying at the Battlecross memorial in Aldborough. From 10am to 4pm, there will be a living history display in the Back Lane car park in Boroughbridge, and an art display by schoolchildren in the Library Jubilee Room.

At 10.30am and 2pm, there will be battle and weapon demonstrations on the car park, and at 11.30am and 3pm (weather permitting), Louise Whittaker, of The Battlefields Trust, will lead guided walks of the battlefield.

BUT, on the day in February 1327 that Edward III (above) was crowned as Isabella and Mortimer’s puppet king, the Scots, sensing English weakness, invaded. Led by the audacious Sir James Douglas – known as “Black Douglas” – the 20,000-strong army advanced through Durham, burning and raping as they went, and reached as far south as Teesside.

This incursion led to another famous battle in which the “crakkis of war” – terrifying fire-spouting cannons – were heard and seen for the first time in Britain, and, by happy coincidence, new research has just led to this battle getting its own page on the Battlefields Trust website.

A 40,000-strong English army assembled in York, with Mortimer bringing in nearly 1,000 mercenaries from Hainault, in Belgium, but the continental mercenaries fell out with the English archers and there was a riot in the city in which more than 100 soldiers died.

On July 1, 1327, this hotch-potch army went north in search of Scots. Although the king was at its head – he had ordered 1,800 flags of St George for the campaign as he selected the saint to lead England to victory for the first time – Mortimer was in control.

They marched through Northallerton and Darlington and arrived in Durham, in atrocious weather, on July 15. Although all the villages were smoking ruins, there were no Scots in sight so they marched on to Newcastle, where they got word that the enemy were camped in Weardale, so they marched back south through the teeming rain.

The Battlefields Trust website, compiled by researcher John Bailey, tells how, on July 30, the Scottish were found camped on the south side of the Wear, on the high ground of Pikeston Fell, opposite Wolsingham. The Scots “lit great fires and made hellish noise”, but refused to come down for a fight, so the English decided to starve them out.

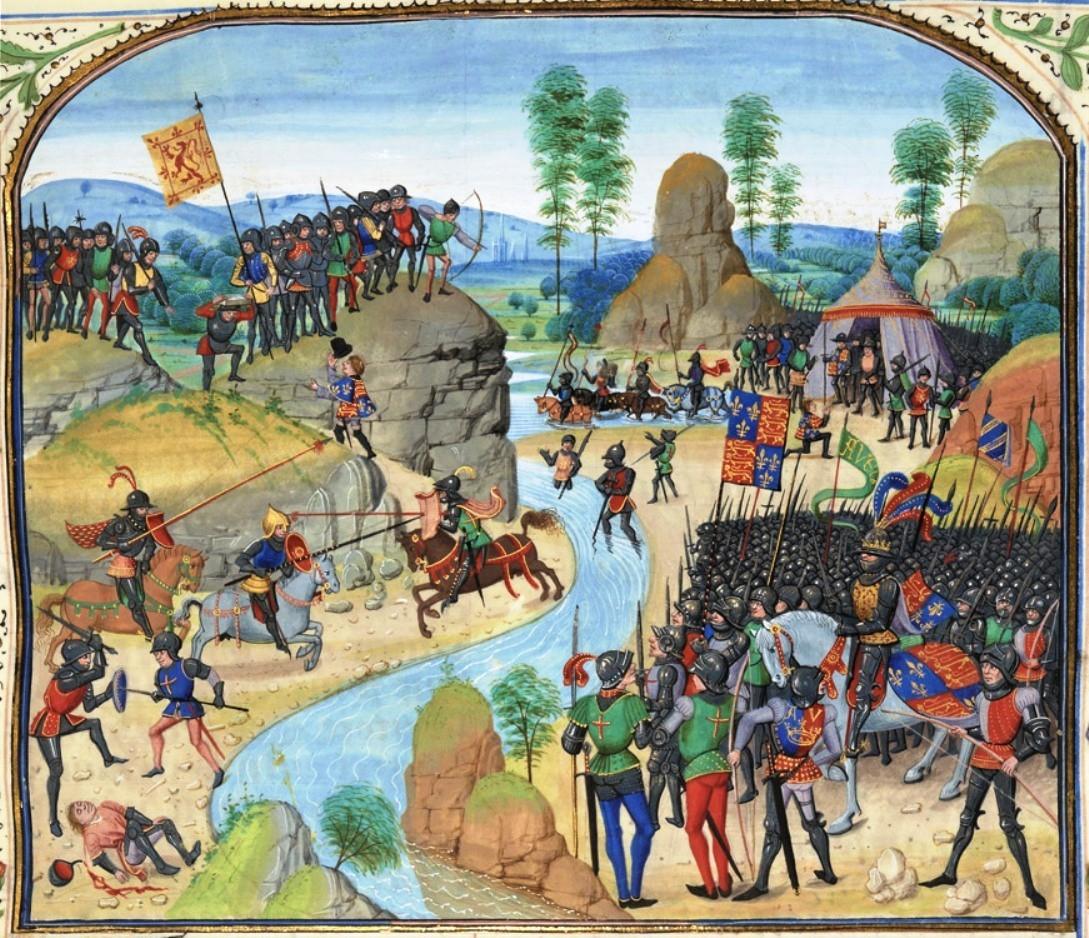

The Battle of Stanhope Park, with the Scots on the left on the high ground above the River Wear with the English wading across the ford to attack

After a three day stand-off, the Scots moved at night to even higher ground, Catterick Moss, opposite Stanhope, where they “set up such a blasting and noise from their horns that is seemed as if all the great devils from hell had assembled together”.

The English followed, plodging west along the A689 and setting up their camp in Stanhope next to the ford.

Stanhope ford was closed in 2012 because vehicles regularly got stuck in it, although Black Douglas made it across in wet weather on August 3/4, 1327

In the early hours of August 4, Black Douglas launched a daring raid across the ford with a couple of hundred selected cavalrymen. Crying “Douglas! Douglas! Ye shall all die, thieves of England”, his men tore into the sleeping Englishmen. He reached the tented pavilion in which Edward III slept near the ford, slashing three of its guyropes so it collapsed in on him, but the English king was protected.

Douglas was driven back across the river by the cannons, which the Scots called the “infernal crakys of war” – the first time gunpowder had been used on a British battlefield.

As the confrontation took place within the Bishop of Durham’s deer park, it is known as the Battle of Stanhope Park.

Stanhope ford can be a tranquil beauty spot in good weather

Hundreds of Englishmen were slain, although a chap called John Chaucer was knighted for his bravery – his son, Geoffrey, would turn his deeds into the Knight’s Tale as part of his Canterbury Tales.

With the weather not improving, the English expected the Scots to surrender as they ran out of food, but on the night of August 6/7, they picked their way across the swollen river and over “impassable” marshland and made their way home.

Mortimer refused to send the English army after them, reducing Edward to “tears of rage”.

“The Weardale campaign was a political success for the Scots, and was ruinously expensive for the English, costing about £70,000, with the cost of the mercenaries alone being £41,000,” says the Battlefields Trust – the English crown’s annual income was about £30,000. Unable to defeat the Scots, the English were forced to sign the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton, in which they relinquished their claim to Scotland.

Edward regarded this as the “shameful peace”, and once he had come of age, he had Mortimer executed. In the 1330s, he returned to defeat the Scots. Then he defeated the French and made England the leading power in Europe – his 50-year reign makes him one of the greatest of English kings.

But it would have been very different if the Scots had got at him at Stanhope as he lay smothered by his own tent.

“The battlefield probably covered the entire village including what is now a public park,” says the Battlefield Trust. “Access to the English position is possible on foot along the A689 road opposite the Dales Centre. There are sufficient public footpaths to enable the battlefield to be walked. The Scottish positions are on the south side of the River Wear and can be viewed by walking south along the B6278 and over the railway level crossing.”

For further information, go to battlefieldstrust.com and click on the Resource Centre.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel