A NEW booklet setting out the place of the Stockton & Darlington Railway in history has just been published by the Friends of the line.

In a clear and concise form, with plenty of pictures, it lays out how this was the railway that got the world on track.

“When the S&DR was designed and built, there was no model of a successful railway to copy,” says the author Caroline Hardie. “No one had yet invented the railway station or signals and other aspects of what we now think of as defining a railway. The S&DR had the vision to use the technology that had been evolving over many years and adapt it for a bigger more ambitious purpose.”

For five years after it opened, the eyes of the world were upon it, as every entrepreneur watched to see if it would fail, and to learn whatever lessons were possible from its success as it proved that the new steam-powered technology would work and, even more importantly, make money.

And so, it lit “the fuse for the explosive expansion of railways across the world and a second wave of the industrial revolution”.

The booklet, which is an ideal starting point for anyone with an interest in the 2025 bicentenary, is available for £5 from the shop section of the Friends’ website, sdr1825.org.uk

Here are ten things we learned from the book:

Many keelmen were brought down from Tyneside to dig the line as they had been made redundant during the great strike on the Tyne in 1822. At the dinner in Stockton Town Hall after the inaugural journey in 1825, among the carefully chosen music played was Weel May the Keel Row to celebrate the keelsmen’s involvement.

An original two-holed sleeper from the Stockton & Darlington Railway

Two thirds of the iron rails for the railway came from the Bedlington Ironworks in Northumberland; the other third and all of the ‘chairs’, which held the rails onto the sleepers, came from south Wales. The 64,000 stone sleeper blocks came from Brusselton, Etherley and Houghton Bank quarries, and were used on the west end of line into Darlington. Young boys were paid 8d a day (£1.91 in today’s values) to drill two holes in 24 blocks for the chairs to go in. On the east end of the line, the oak sleeper blocks came from Portsmouth by ship into Stockton.

Stockton Town Hall in 1927

After the first journey on September 25, 1825, a banquet was held for 102 VIPs in Stockton Town Hall. The evening concluded with 23 toasts, the last of which was to George Stephenson, the line’s engineer and designer. By that time, though, he had left, exhausted

In 1823, two years before the line opened, the proprietors had added “passengers” to the list of minerals and goods that they intended to carry. By 1827, the line was carrying 30,000 passengers a year, which represented an eightfold increase in local travel. This mix of people and goods set the model for subsequent railways

In 1823, when the S&DR said to Parliament it planned to use locomotive power, a clerk at the House of Commons had to check to see what a locomotive was. The S&DR fervently promoted the use of locomotives on other railways – perhaps because Edward Pease had invested in setting up Robert Stephenson & Co in Newcastle to make locomotives.

In 1826, the S&DR realised that its passengers and customers needed shelter and refreshment. It had inns built at Stockton, Darlington and Heighington – all of which still stand, although only the Railway Tavern in Northgate still trades. These were prototype stations. Private businesses such as the New Inn at Yarm, opened by the line’s chairman, Thomas Meynell, also got in on the act. It is now the Cleveland Bay (above).

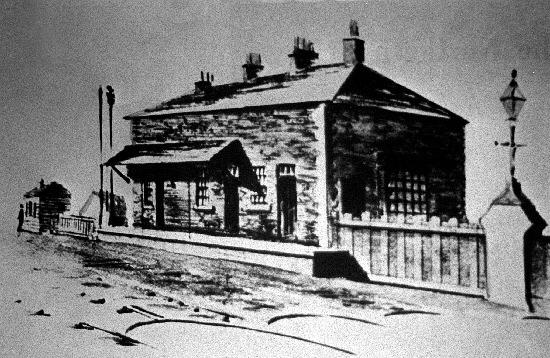

In Darlington in 1827, the S&DR built a new kind of building – “a merchandising station” to handle goods (above). In 1833, this building off North Road was converted into a passenger station, with a cottage on the lower floor and a shop, booking office and waiting room above. The cottage and the shop were let to Mary Simpson at £5pa, in return she was to “keep the coach office clean afford every necessary accommodation to coach passengers”. Mary was the first woman employee of the S&DR. The station was demolished in 1864.

If a business were within five miles of the line, it was given free access to build its own sidings. This created a 10 mile wide, 26 mile long economic growth corridor as mines and quarries were opened on the farmland alongside it.

Engineers from Prussia visited Timothy Hackworth in Shildon twice in the line’s early years as he battled to make the first engines reliable, often working by candlelight into the night to get them ready for the next day’s working. He rebuilt Locomotion No 1 three times, but really his high point was Royal George, an engine he built in 1827 which included everything he learned so far and which proved to the watching world that steampower really was the future.

“The success of the Darlington railway experiment, and the admirable manner in which the loco-motive engine does all, and more than all that was expected of it, seems to have spread far and wide the conviction of the immense benefits to be derived from the construction of new railways.” The Times, December 2, 1825

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here