WHEN people think about the D-Day landings, many automatically picture the 1998 film Saving Private Ryan. If you’re my age, you might also think about Medal of Honour Frontline, a computer game that came out a few years later.

When I mention the Battle of Arnhem to people, many automatically talk about the film A Bridge Too Far, the 1977 blockbuster movie starring Sean Connery and Anthony Hopkins, centred around the British disaster in the southern Dutch town.

Lesser-known connections might be the fact that Richard Adams based his 1972 book Watership Down on the exploits of his fellow officers during the Battle, or that Audrey Hepburn spent those nine bloody days in September 1944 cowering in her family home within earshot of the fighting around the bridge.

When we think of these great events in our history, there is usually a cultural connection that we refer to, which in itself is credit to the makers for drawing our attention to them. But we don’t often consider how close these events are to our own lives. Grandad’s old mutterings of what he did in the war aren’t as exciting as watching Tom Hanks storm Omaha Beach. Or are they?

Today marks the 77th anniversary of the end of the ill-fated Operation Market Garden, which started oln September 17, 1944, with a division of British airborne soldiers was tasked with capturing the Arnhem bridge over the Lower Rhine. The Second World War was nearing its final stages and the Allies, having landed in Normandy on D-Day, had swept through northern France and were about to enter the Netherlands. The airborne soldier – paratroopers – were dropped ahead of the advancing Allies to capture crucial bridges and wipe out German resistance, and so speed up the advance.

Having parachuted in, the soldiers were supposed to be relieved by a British Armoured Corps after 48 hours, but nine days later, just less than 20 per cent of them had made it across the river to safety.

The other 80 per cent were either dead, captured or still fighting for their lives.

I have great interest in military history, and in particular, the Battle of Arnhem, and I have attended the September commemorations in Holland many times but after being elected as a Darlington councillor in 2019, I decided to find out how many of our townsmen had fought in this incredible battle.

I quickly came across Staff Serjeant Peter Hill, a glider pilot who had fought through nine days of hell only to drown during the evacuation – his story was told in Memories 298. He was last seen by fellow glider pilot and Darlingtonian Staff Serjeant David Hartley who survived the battle. Ahead of the 75th anniversary in 2019, I held a special service on Albert Hill for him and was lucky enough to meet two of his relatives, who were pleased to hear that I was going to lay a wreath on his grave on behalf of the council.

Before that trip, I also found Darlington-born Major Joseph Esmond Miller, a member of the Airlanding Field Ambulance at Arnhem who stayed behind with the wounded. He was be taken prisoner and remained in captivity until the end of the war. Miller had won the Military Cross for his actions in Sicily with the Division and was to become a Major General and Director of Medical Services at HQ UK Land Forces in 1975.

Then there was Thomas Laycock, a member of the Border Regiment who also escaped across the river, only to die in a plane crash six months later on the way to the disarm German forces in Norway. He too had also served in Sicily.

Mike Renton at the grave of Michael Hendrick in the Netherlands

While I was in Arnhem in 2019, I found the grave of Darlington’s Michael Hendrick, a member of the King’s Own Scottish Border Regiment, who was tragically killed six days into the battle.

By this time, I was beginning to feel that we had a real connection to Arnhem given that so much of our blood was spilt there.

As this year’s anniversary approached, I decided to post a day-to-day commentary of Sgt Peter Hill’s movements during the battle. Not much was written about his personal exploits, but members of his unit had been quite thorough in their written recollections.

On my first post, which I shared to a Darlington-wide Facebook page, two people came forward with new Arnhem names. I had to know more!

I first spoke to the grandson of Maurice Tenwick, the regimental quartermaster sergeant of the South Staffordshire Regiment, a battalion that suffered heavy casualties during the battle having been in the wrong place at the wrong time. He also went to Norway in 1945 and received a personal letter from Field Marshall Montgomery commending him on his “great devotion to duty” (below).

But he never wrote or spoke about his time at Arnhem, possibly because it had such a negative effect on his life. His grandson thinks that survivor’s guilt might have played a part, leading him to alcoholism. When he died in 1975, his wife said it was the war that killed him.

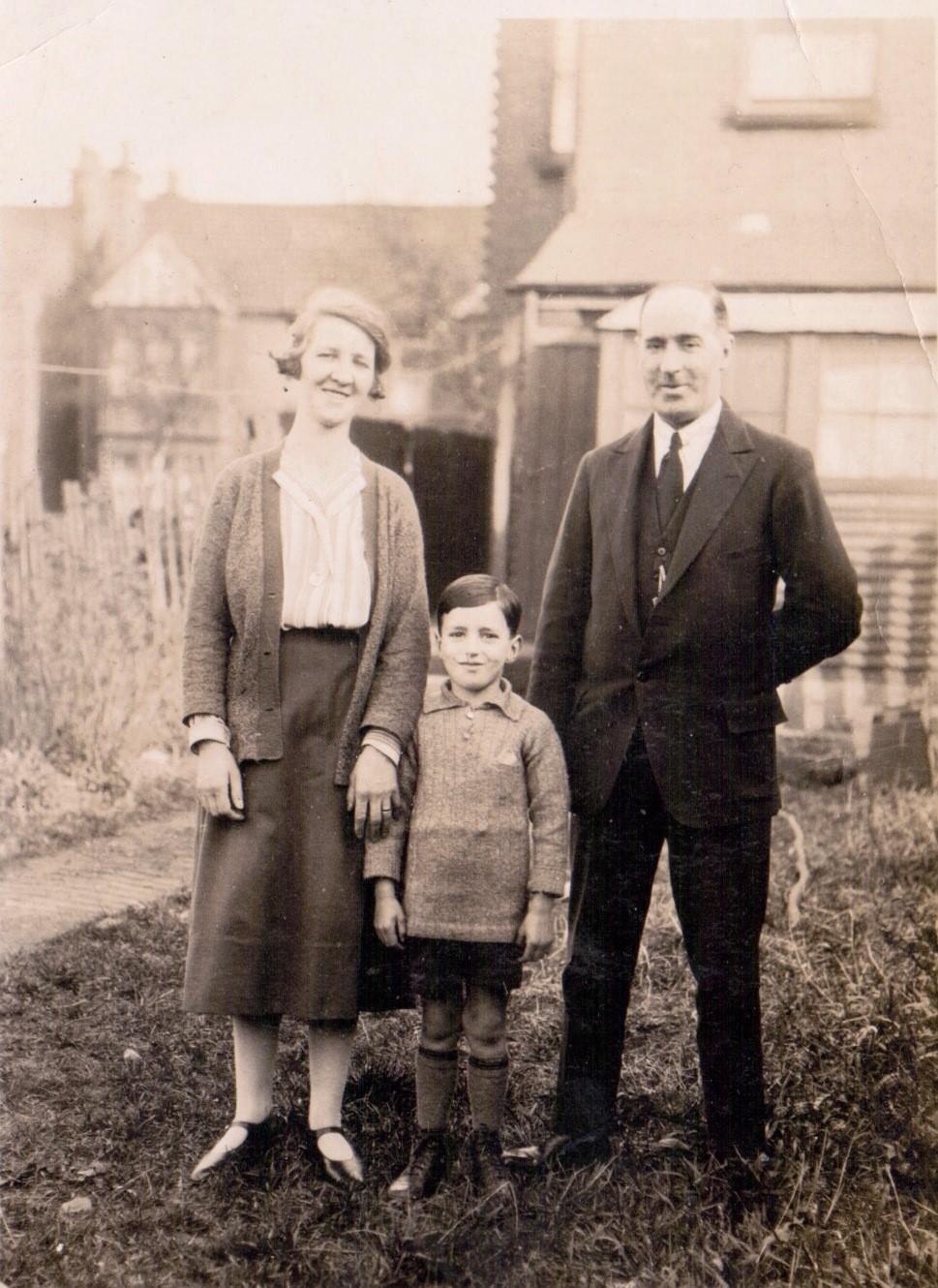

Then I spoke to the son of Thomas Gillie (above), a sergeant in the Royal Engineers. His small unit was a part of only 700 men who made it to the bridge with John Frost, played by Anthony Hopkins in A bridge Too Far, and his battalion.

Tommy Gillie on his wedding day

For more than four days, Tommy was involved in some of the fiercest fighting of the battle, defending a schoolhouse on the ramparts of the bridge where tanks could roll right up and fire directly through the windows.

After getting drunk on wine he found while digging a foxhole, he was soon taken prisoner and after the war went back to work for Billy Armstrong of the Darlington builders, Bussey & Armstrong.

A family tribute to Tommy Gillie

It was during this conversation that I made a major breakthrough. Tommy’s son, Stephen, mentioned that Tommy lived in the same street as another Arnhem veteran and old friend Ernie Sedgwick, who had celebrated his 100th birthday in August.

After many phone calls, I managed to arrange a meeting with him on Thursday (below).

Meeting him, you wouldn’t think he was 100, although his card from the Queen is proudly displayed in the sitting room. Ernie had joined the Durham Light Infantry as a reservist in 1937 and was on annual camp when news of the war was broken. As part of the British Expeditionary Force he had been evacuated from Dunkirk then joined the Royal Artillery, tasked with the air defence of Hull.

Darlington DLI veteran Ernest Sedgewick celebrates his 100th birthday

Picture: SARAH CALDECOTT.

Looking for something different, Ernie volunteered for the Parachute Regiment, and joined 6th Airborne Division during the invasion of Normandy on D-Day. Wounded by shrapnel in the chest, he was sent back to England for rehabilitation.

After being deemed fit, he was re-allocated to 1st Airborne Division just in time for Operation Market Garden.

As a member of the 2nd Battalion 1st Parachute Brigade, he was one of the first soldiers on the ground and spent nine days in hell before being evacuated across the river, where Peter Hill died.

Ernie had so much to say, and I came away thinking about how the fighting around Arnhem 77 years ago was like the final scenes of Saving Private Ryan. Many parallels can be drawn: constant attacks from all directions, house to house and hand to hand fighting, tanks and artillery in the streets blasting through walls. Times that 30 minutes by eight days and you might know the half of it.

We can’t really imagine what it must have been like to experience something so terrible, but when we have that connection on our doorstep here in Darlington, it is only right that we make an effort to remember it.

As I was leaving, Ernie wanted to make it clear that he was not a hero, he was just an ordinary soldier.

I think the war correspondent Alan Wood, who was at Arnhem for the duration, had the perfect answer to that, when he said: "If in years to come any man says to you 'I fought at Arnhem', take off your hat to him and buy him a drink, for his is the stuff for which England's greatness is made."

- Mike Renton is a Darlington Conservative councillor

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel